Shloka

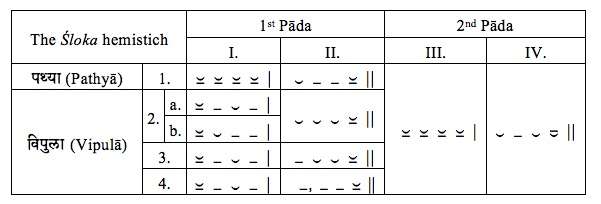

Shloka (meaning "song", from the root śru, "hear"[1]) is a category of verse line developed from the Vedic Anustubh poetic meter. It is the basis for Indian epic verse, and may be considered the Indian verse form par excellence, occurring, as it does, far more frequently than any other meter in classical Sanskrit poetry.[1] The Mahabharata and Ramayana, for example, are written almost exclusively in shlokas.[2] The traditional view is that this form of verse was involuntarily composed by Valmiki in grief, the author of the Ramayana, on seeing a hunter shoot down one of two birds in love.[3] The shloka is treated as a couplet. Each hemistich (half-verse) of 16 syllables, composed of two Pādas of eight syllables, can take either a pathyā ("normal") form or one of several vipulā ("extended") forms. The form of the second foot of the first Pāda (II) limits the possible patterns the first foot (I) may assume, as in the scheme below. Alternatively, a shloka is four quarter-verses, each with eight syllables.[3]

The Pathyā and Vipulā half-verses are arranged in the table above in order of frequency of occurrence. Out of 2579 half-verses taken from Kalidasa, Magha, Bharavi, and Bilhana, each of the four admissible forms of shloka in the above order claims the following share: 2289, 116, 89, 85.[4]

The metrical constraints on a hemistich in terms of its two constituent padas are as follows:[5]

- General

- The 1st and 8th syllables of both pādas are anceps.

- The 2nd and 3rd syllables cannot both be light (laghu, "⏑") in either pāda; i.e. one or both of the 2nd and 3rd syllables must be heavy (guru, "–") in both pādas.

- Syllables 2-4 of the second pāda cannot be a ra-gaṇa (the pattern "– ⏑ –")

- Syllables 5-7 of the second pāda must be a ja-gaṇa ("⏑ – ⏑") This enforces an iambic cadence.

- Normal form (pathyā)

- Syllables 5-7 of the first pāda must be a ya-gaṇa ("⏑ – –")

- Variant forms (vipulā): The 4th syllable of the first pāda is heavy. In addition, one of the following is permitted:

- na-vipulā: Syllables 5-7 are a na-gaṇa ("⏑ ⏑ ⏑")

- bha-vipulā: Syllables 2-7 are ra-bha gaṇas ("– ⏑ – – ⏑ ⏑") or ma-bha gaṇas with a caesura in between ("– – – , – ⏑ ⏑")

- ma-vipulā: Syllables 2-7 are ra-ma gaṇas with a caesura after the 5th ("– ⏑ – – , – –")

- ra-vipulā: Syllables 5-7 are a ra-gaṇa following a caesura (", – ⏑ –")

Noteworthy is the avoidance of an iambic cadence in the first pāda. By comparison, Syllables 5-7 of any pāda in the old Vedic anuṣṭubh is typically a ja-gaṇa ("⏑ – ⏑"), or a dijambus.

An example of an anuṣṭubh stanza which fails the classical requirements of a shloka is from the Shatapatha Brahmana

- āsandīvati dhānyādaṃ rukmiṇaṃ haritasrajam

- abadhnādaśvaṃ sārańgaṃ devebhyo janamejayaḥ[6]

- "In Āsandîvat, Janamejaya bound for the gods a black-spotted, grain-eating

- horse, adorned with a golden ornament and with yellow garlands."[7]

A shloka, states Monier-Williams, can be "any verse or stanza; a proverb, saying..".[3]

The shloka and Anushtubh meter has been the most popular verse style in classical and post-classical Sanskrit works.[8] It is octosyllabic, next harmonic to Gayatri meter that is sacred to the Hindus. A shloka has a rhythm, offers flexibility and creative space, but has embedded rules of composition.[8] The Anushtubh is present in Vedic texts, but its presence is minor, and Trishtubh and Gayatri meters dominate in the Rigveda for example.[9] A dominating presence of shlokas in a text is a marker that the text is likely post-Vedic.[10]

The shloka structure is embedded in the Bhagavad Gita, the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the Puranas, Smritis and scientific treatises of Hinduism such as Sushruta Samhita and Charaka Samhita.[11][10][12] The Mahabharata, for example, features many verse meters in its chapters, but an overwhelming proportion of the stanzas, 95% are shlokas of the anustubh type, and most of the rest are tristubhs.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 Macdonell, Arthur A., A Sanskrit Grammar for Students, Appendix II, p. 232 (Oxford University Press, 3rd edition, 1927).

- ↑ Hopkins 1901, pp. 191-192.

- 1 2 3 Monier Monier-Williams (1923). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 1029–1030.

- ↑ Macdonell, Arthur A., A Sanskrit Grammar for Students, Appendix II, p. 233 (Oxford University Press, 3rd edition, 1927)

- ↑ Steiner, Appendix 4; translated: Macdonald, Appendix

- ↑ SBM.13.5.4.2

- ↑ Eggeling's translation

- 1 2 Horace Hayman Wilson 1841, pp. 418-422.

- ↑ Kireet Joshi (1991). The Veda and Indian Culture: An Introductory Essay. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-81-208-0889-8.

- 1 2 Friedrich Max Müller (1860). A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature. Williams and Norgate. pp. 67–70.

- ↑ Arnold 1905, p. 11, 50 with note ii(a).

- ↑ Vishwakarma, Richa; Goswami, PradipKumar (2013). "A review through Charaka Uttara-Tantra". AYU. 34 (1): 17.

- ↑ Hopkins 1901, p. 192.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Edward Vernon (1905). Vedic Metre in its historical development. Cambridge University Press (Reprint 2009). ISBN 978-1113224446.

- Brown, Charles Philip (1869). Sanskrit prosody and numerical symbols explained. London: Trübner & Co.

- Colebrooke, H.T. (1873). "On Sanskrit and Prakrit Poetry". Miscellaneous Essays. 2. London: Trübner and Co. pp. 57–146.

- Coulson, Michael (1976). Teach Yourself Sanskrit. Teach Yourself Books. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Hahn, Michael (1982). Ratnākaraśānti's Chandoratnākara. Kathmandu: Nepal Research Centre.

- Friedrich Max Müller; Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1886). A Sanskrit grammar for beginners (2 ed.). Longmans, Green. p. 178. PDF

- Hopkins, E.W. (1901). "Epic versification". The Great Epic of India. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

- Patwardhan, M. (1937). Chandoracana. Bombay: Karnataka Publishing House.

- Rocher, Ludo (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225

- Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-018159-3.

- Horace Hayman Wilson (1841). An introduction to the grammar of the Sanskrit language. Madden.

External links

- Shloka, Shuroka (Japanese) Dictionary of Buddhism

- To read Akshara slokams in Malayalam

- Link to Malayalam Aksharaslokam