13-Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(9Z,11E,13S)-13-Hydroxy-9,11-octadecadienoic acid | |

| Other names

13(S)-HODE, 13S-HODE | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChemSpider | 4947055 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C18H32O3 | |

| Molar mass | 296.45 g·mol−1 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

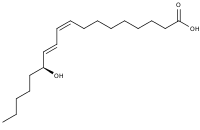

13-Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE) is the commonly used term for 13(S)-hydroxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13(S)-HODE). The production of 13(S)-HODE is often accompanied by the production of its stereoisomer, 13(R)-hydroxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13(R)-HODE). The adjacent figure gives the structure for the (S) stereoisomer of 13-HODE. Two other naturally occurring 13-HODEs that may accompany the production of 13(S)-HODE are its cis-trans (i.e., 9E,11E) isomers viz., 13(S)-hydroxy-9E,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13(S)-EE-HODE) and 13(R)-hydroxy-9E,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13(R)-EE-HODE). Studies credit 13(S)-HODE with a range of clinically relevant bioactivities; recent studies have assigned activities to 13(R)-HODE that differ from those of 13(S)-HODE; and other studies have proposed that one or more of these HODEs mediate physiological and pathological responses, are markers of various human diseases, and/or contribute to the progression of certain diseases in humans. Since, however, many studies on the identification, quantification, and actions of 13(S)-HODE in cells and tissues have employed methods that did not distinguish between these isomers, 13-HODE is used here when the actual isomer studied is unclear.

A similar set of 9-Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (9-HODE) metabolites (i.e., 9(S)-HODE), 9(R)-HODE, 9(S)-EE-HODE), and 9(R)-EE-HODE) occurs naturally and particularly under conditions of oxidative stress forms concurrently with the 13-HODEs; the 9-HODEs have overlapping and complementary but not identical activities with the 13-HODEs. Some recent studies measuring HODE levels in tissue have lumped the four 9-HODEs with the four 13-HODEs to report only on total HODEs (tHODEs). tHODEs have been proposed to be markers for certain human disease. Other studies have lumped together the 9-(S), 9(R), 13 (S)-, and 13(R)-HODEs along with the two ketone metabolites of these HODEs, 13-oxoODE (13-oxo-9Z,12E-octadecadienoic acid) and 9-oxoODE, reporting only on total OXLAMs (oxidized linoleic acid metabolites); the OXLAMs have been implicated in working together to signal for pain perception.

Pathways making 13-HODEs

15-Lipoxygenase 1

15-lipoxygenase 1 (ALOX15), while best known for converting the 20 carbon polyunsaturated fatty acid, arachidonic acid, into a series of 15-hydroxylated arachidonic acid metabolites (see 15-hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid), actually prefers as its substrate the 18 carbon polyunsaturated fatty acid, linoleic acid, over arachidonic acid, converting it to 13-hydroperoxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-HpODE).[1][2] The enzyme acts in a highly stereospecific manner, forming 13(S)-hydroperoxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13(S)-HpODE) but comparatively little or no 13(R)-hydroperoxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13(R)-HpODE) -.[3][4] In cells, 13(S)-HpODE is rapidly reduced by peroxidases to 13(S)-HODE.[1][5] ALOX15 is fully capable of metabolizing the linoleic acid that is bound to phospholipid[6] or cholesterol[7] to form 13(S)-HpODE-bound phospholipids and cholesterol that are rapidly converted to their corresponding 13(S)-HODE-bound products.

15-lipoxygenase 2

15-lipoxygenase type 2 (ALOX15B) strongly prefers arachidonic acid over linoleic acid and in consequence is relatively poor in metabolizing linoleic acid to 13(S)-HpODE (which is then converted to 13(S)-HODE) compared to 15-lipoxygenase 1;[8] nonetheless, it can contribute to the production of these metabolites.[2][9]

Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2

Cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) metabolize linoleic acid to 13(S)-HODE with COX-2 exhibiting a higher preference for linoleic acid and therefore producing far more of this product than its COX-1 counterpart;[10] consequently, COX-2 appears to be the principle COX making 13(S)-HODE in cells expressing both enzymes.[11] Concurrently with their production of 13(S)-HODE, these enzymes also produce smaller amounts of 9(R)-HODE.[12][13]

Cytochrome P450

Cytochrome P450 microsomal enzymes metabolize linoleic acid to a mixture of 13-HODEs and 9-HODEs; these reactions produce racemic mixtures in which the R stereoisomer predominates, for instance by a R/S ratio of 80%/20% for both 13-HODE and 9-HODE in human liver microsomes.[14][15][16]

Free radical and singlet oxygen oxidations

Oxidative stress in cells and tissues produces Free radical and singlet oxygen oxidations of linoleic acid to generate 13-HpODEs, 9-HpODEs, 13-HODEs, and 9-HODEs; these non-enzymatic reactions produce or are suspected but not proven to produce approximately equal amounts of their S and R stereoisomers.[17][18][19] Free radical oxidations of linoleic acid also produce 13-EE-HODE, 9-hydroxy-10E,12-E-octadecadienoic acid, 9-hydroxy-10E,12-Z-octadecadienoic acid, and 11-hydroxy-9Z,12Z-octadecaenoic acid while singlet oxygen attacks on linoleic acid produce (presumably) racemic mixtures of 9-hydroxy-10E,12-Z-octadecadienoic acid, 10-hydroxy-8E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid, and 12-hydroxy-9Z-13-E-octadecadienoic acid.[20][21] 4-Hydroxynonenal (i.e. 4-hydroxy-2E-nonenal or HNE) is also a peroxidation product of 13-HpODE.[22] Since oxidative stress commonly produces both free radicals and singlet oxygen, most or all of these products may form together in tissues undergoing oxidative stress. Free radical and singlet oxygen oxidations of linoleic acid produce a similar set of 13-HODE metabolites (see 9-Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid). Studies attribute these oxidations to be major contributors to 13-HODE production in tissues undergoing oxidative stress including in humans sites of inflammation, steatohepatitis, cardiovascular disease-related atheroma plaques, neurodegenerative disease, etc. (see oxidative stress).[23][24]

Metabolism of 13(S)-HODE

Like most polyunsaturated fatty acids and mono-hydroxyl polyunsaturated fatty acids, 13(S)-HODE is rapidly and quantitatively incorporated into phospholipids;[25][25] the levels of 13(S)-HODE esterified to the sn-2 position of phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol, and phosphatidylethanolamine in human psoriasis lesions are significantly lower than those in normal skin; this chain shortening pathway may be responsible for inactivating 13(S)-HODE.[26] 13(S)-HODE is also metabolized by peroxisome-dependent β-oxidations to chain-shortened 16-carbon, 14-carbon, and 12-carbon products which are released from the cell;[27] this chain-shortening pathway may serve to inactive and dispose of 13(S)-HODE.

13(S)-HODE is oxidized to 13-oxo-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-oxo-HODE or 13-oxoODE) by a NAD+-dependent 13-HODE dehydrogenase, the protein for which has been partially purified from rat colon.[28][29][30] The formation of 13-oxo-ODE may represent the first step in 13(S)-HODEs peroxisome-dependent chain shortening but 13-oxo-ODE has its own areas of biological importance: it accumulates in tissues,[31][32] is bioactive,[33][34] and may have clinically relevance as a marker for[35][36] and potential contributor to[37] human disease. 13-Oxo-ODE itself may react with glutathione in a non-enzymatic Michael reaction or a glutathione transferase-dependent reaction to form 13-oxo-ODE products containing a 11 trans double bound and glutathione attached to carbon 9 in a mixture of S and R diastereomers; these two diasteromers are major metabolites of 13(S)-HODE in cultured HT-29 human colon cancer cells.[38] Colonic mucosal explants from Sprague-Dawley rats and human colon cancer HT29 cells add glutathione to 13-oxo-ODE in a Michael reaction to form 13-oxo-9-glutatione-11(E)-octadecaenoic acid; this conjugation reaction appears to be enzymatic and mediated by a glutathione transferase.[39][40] Since this conjugate may be rapidly exported from the cell and has not yet been characterized for biological activity, it is not clear if this transferase reaction serves any function beyond removing 13-oxo-ODE from the cell to limit its activity.[41]

Activities of 13-HODEs

Stimulation of Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

13-HODE, 13-oxoODE, and 13-EE-HODE (along with their 9-HODE counterparts) directly activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ).[42][43][44] This activation appears responsible for the ability of 13-HODE (and 9-HODE) to induce the transcription of PPARγ-inducible genes in human monocytes as well as to stimulate the maturation of these cells to macrophages.[42] 13(S)-HODE (and 9(S)-HODE) also stimulate the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta (PPARβ) in a model cell system; 13-HODE (and 9-HODE) are also proposed to contribute to the ability of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) to activate PPARβl: LDL containing phospholipid-bound 13-HODE (and 9-HODE) is taken up by the cell and then acted on by phospholipases to release the HODEs which in turn directly activate PPARβl.[45]

Stimulation of TRPV1 receptor

13(S)-HODE, 13(R)-HODE and 13-oxoODE, along with their 9-HODE counterparts, also act on cells through TRPV1. TRPV1 is the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 receptor (also termed capsaicin receptor or vanilloid receptor 1). These 6 HODEs, dubbed, oxidized linoleic acid metabolites (OXLAMs), individually but also and possibly to a greater extent when acting together, stimulate TRPV1-dependent responses in rodent neurons, rodent and human bronchial epithelial cells, and in model cells made to express rodent or human TRPV1. This stimulation appears due to a direct interaction of these agents on TRPV1 although reports disagree on the potencies of the (OXLAMs) with, for example, the most potent OXLAM, 9(S)-HODE, requiring at least 10 micromoles/liter[46] or a more physiological concentration of 10 nanomoles/liter[47] to activate TRPV1 in rodent neurons. The OXLAM-TRPV1 interaction is credited with mediating pain sensation in rodents (see below).

Stimulation of GPR132 receptor

13(S)-HpODE, and 13(S)-HODE directly activate human (but not mouse) GPR132 (G protein coupled receptor 132, also termed G2A) in Chinese hamster ovary cells made to express these receptors; they are, however, far weaker GPR132 activators than 9(S)-HpODE or 9(S)-HODE.[48][49] GPR132 was initially described as a pH sensing receptor; the role(s) of 13(S)-HpODE and 13(S)-HODE as well as 9(S)-HpODE, 9(S)HODE, and a series or GPR132-activating arachidonic acid hydroxy metabolites (i.e. HETEs) in activating G2A under the physiological and pathological conditions in which G2A is implicated (see GPR132 for a lists of these conditions) have not yet been determined. This determination, as it might apply to humans, is made difficult by the inability of these HODEs to activate rodent GPR132 and therefore to be analyzed in rodent models.

Involvement in mitochondria degradation

In the maturation of the red blood cell lineage (see erythropoiesis) from mitochondria-bearing reticulocytes to mature mitochondria-free erythrocytes in rabbits, the mitochondria accumulate phospholipid-bound 13(S)-HODE in their membranes due to the action of a lipoxygenase which (in rabbits, mice, and other sub-primate vertebrates) directly metabolizes linoleic acid-bound phospholipid to 13(S)-HpODE-bound phospholipid which is rapidly reduced to 13(S)-HODE-bound phospholipid.[6] It is suggested that the accumulation of phospholipid-bound 13(S)-HpODE and/or 13(S)-HODE is a critical step in rendering mitochondria more permeable thereby triggering their degradation and thence maturation to erythrocytes.[6][50] However, functional inactivation of the phospholipid-attacking lipoxygenase gene in mice does not cause major defects in erythropoiesis.[51] It is suggested that mitochondrial degradation proceeds through at least two redundant pathways besides that triggered by lipoxygenase-dependent formation of 13(S)-HpODE- and 13(S)-HODE-bound phospholipids viz., mitochondrial digestion by autophagy and mitochondrial exocytosis.[52] In all events, formation of 13(S)-HODE bound to phospholipid in mitochondrial membranes is one pathway by which they become more permeable and thereby subject to degradation and, as consequence of their release of deleterious elements, to cause cell injury.[53]

Stimulation of blood leukocytes

13-HODE (and 9-HODE) are moderately strong stimulators of the directed migration (i.e. chemotaxis) of cow and human neutrophils in vitro[54] whereas 13(R)-HODE (and 9(R)-HODE, and 9(S)-HODE) are weak stimulators of the in vitro directed migration of the human cytotoxic and potentially tissue-injuring lymphocytes, i.e. natural killer cells.[55] These effects may contribute to the pro-inflammatory and tissue-injuring actions ascribed to 13-HODEs (and 9-HODEs).

Involvement of 13-HODEs in human diseases

Atherosclerosis

In atherosclerosis, an underlying cause of Coronary artery disease and strokes, atheromatous plaques accumulate in the vascular tunica intima thereby narrowing blood vessel size and decreasing blood flow. In an animal model and in humans 13-HODE (primarily esterified to cholesterol, phospholipids, and possibly other lipids) is a dominant component of these plaques.[56][57][58][59] Since these studies found that early into the progression of the plaques, 13-HODE consisted primarily of the S stereoisomer while more mature plaques contained equal amounts of S and R stereoisomers, it was suggested that 15-LOX-1 contributes to early accumulation while cytochrome and/or free radical pathways contributes to the later accumulation of the plaques. Further studies suggest that 13(S)-HODE contributes to plaque formation by activating the transcription factor, PPARγ (13(R)-HODE lacks this ability[60]), which in turn stimulates the production of two receptors on the surface of macrophages resident in the plaques, 1) CD36, a scavenger receptor for oxidized low density lipoproteins, native lipoproteins, oxidized phospholipids, and long-chain fatty acids, and 2) adipocyte protein 2 (aP2), a fatty acid binding protein; this may cause macrophages to increase their uptake of these lipids, transition to lipid-laden foam cells, and thereby increase plaque size.[61] The 13(S)-HODE/PPARγ axis also causes macrophages to self-destruct by activating apoptosis-inducing pathways;, this effect may also contribute to increases in plaque size.[62] These studies suggest that 13-HODE-producing metabolic pathways,[63] PPARγ,[64][65] CD36,[66] and aP2[67] may be therapeutic targets for treating atherosclerosis-related diseases. Indeed, Statins, which are known to suppress cholesterol synthesis by inhibiting an enzyme in the cholesterol synthesis pathway, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase HMG-CoA reductase, are widely used to prevent atherosclerosis and atherosclerosis-related diseases. Statins also inhibit PPARγ in human macrophages, vascular endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells; this action may contribute to their anti-atherogenic effect.[68]

Asthma

In guinea pigs, 13(S)-HODE, when injected intravenously, causes a narrowing of lung airways and, when inhaled as an aerosol, mimics the asthmatic hypersensitivity to agents that cause bronchoconstriction by increasing airway narrowing responses to methacholine and histamine.[69] In a mouse model of allergen-induced asthma, 13-HODE levels are elevated,[70] in the latter mouse model, the injection of antibody directed against 13(S)-HODE reduced many of the pathological and physiological features of asthma,.[53] mouse forced to overexpress in lung the mouse enzyme (12/15-lipoxygenase) that metabolizes linoleic acid to 13(S)-HODE exhibited elevated levels of this metabolite in lung as well as various pathological and physiological features of asthma,[70] and the instillation of 13(S)HODE replicated many of these features of asthma,[71] In the mouse model of asthma and in the human disease, epithelial cells of lung airways show various pathological changes including disruption of their mitochondria[53][70][72] 13(S)-HODE causes similar disruptive changes in the mitochondria of cultured Beas 2B human airway epithelial cells.[53] Furthermore, human suffers of asthma exhibit increased levels of 13-HODE in their blood, sputum, and washings form their lung alveola (i.e. bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of BAL) and human eosinophils, which are implicated in contributing to human asthma, metabolize linoleic acid to 13-HODE (and 9-HODE) to a far greater extent than any other type of leukocyte.[73] The mechanism responsible for 13-HODE's impact on airway epithelial cells may involve its activation of the TRPV1 receptor (see previous section on TRPV1): this receptor is highly expressed in mouse and human airway epithelial cells and in Beas 2B human airway epithelial cells and, furthermore, suppression of TRPV1 expression as well as a TPRV1 receptor inhibitor (capsazepan) block mouse airway responses to 13(S)-HODE.[53] While much further work is needed, these pre-clinical studies allow that 13(S)-HODE, made at least in part by eosinophils and operating through TRPV1, may be responsible for the airways damage which occurs in the more severe forms of asthma and that pharmacological inhibitors of TRPV1 may eventually proved to be useful additions to the treatment of asthma.

Cancer

Colon Cancer

Familial adenomatous polyposis is a syndrome that includes the propensity to develop colorectal cancer (and other cancers) due to the inheritance of defective mutations in either the APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) or MUTYH gene. These mutations lead to several abnormalities in the regulation of the growth of colon epithelial cells that ultimately lead to the development of intestinal polyps which have a high risk of turning cancerous.[74] One of the abnormalities found in the APC disease is progressive reductions in 15-lipoxygenase 1 along with its product, 13-HODE (presumed but not unambiguously shown to be the S stereoisomer) as the colon disease advances from polyp to malignant stages; 15-HETE, 5-lipoxygenase, 12-lipoxygenase, and 15-lipoxygenase-2, and selected metabolites of the latter lipoxygenases show no such association.[75][76][77] Similarly selective reductions in 15-lipoxygenase 1 and 13-HODE occur in non-hereditary colon cancer.[78][79][80] 13(S)-HODE inhibits the proliferation and causes the death (apoptosis) of cultured human colon cancer cells.[60][81][82][83] Animal model studies also find that the 15-lipoxygenase 1 / 13-HODE axis inhibits the development of drug-induced colon cancer as well as the growth of human colon cancer cell explants.[76] These results suggest that 15-lipoxygenase 1 and its 13(S)-HODE product are factors in promoting genetically-associated and -non-associated colon cancers; they function by contributing to the suppression of the development and/or growth of this cancer and when reduced or absent allow its unrestrained, malignant growth.

Breast Cancer

13(S)-HODE stimulates the proliferation of human MCF-7 estrogen receptor positive and MBA-MD-231 estrogen receptor negative human breast cancer cell lines (see List of breast cancer cell lines) in culture);[84] its production appears necessary for epidermal growth factor and tumor growth factor α to stimulate cultured BT-20 human breast cancer cells to proliferate[85] and for human breast cancer xenografts to grow in mice.;[86] and among a series of 10 polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites quantified in human breast cancer tissue, only 13-HODE (stereoisomer not defined) was significantly elevated in rapidly growing, compared to slower growing, cancers.[87] The results of these studies suggest that 13(S)-HODE may act to promote the growth of breast cancer in humans.

Prostate Cancer

15-LOX 1 is overexpressed in prostate cancerous compared to non-cancerous prostate tissue and the levels of its expression in cultured various human prostate cancer cell lines correlates positively with their rates of proliferation and increases the proliferation response of prostate cancer cells to epidermal growth factor and insulin-like growth factor 1); its levels in human prostate cancer tissues also correlates positively with the cancers' severity as judged by the cancers' Gleason score; and overexpressed 15-LOX 1 appears to not only increase prostate cancer cell proliferation, but also promotes its cell survival by stimulating production and of insulin-like growth factor 1 and possibly altering the Bcl-2 pathway of cellular apoptosis as well as increases prostate tumor vascularization and thereby metastasis by stimulating production of vascular endothelial growth factor. These 15-LOX 1 effects appear due to the enzyme's production of 13(S)-HODE.[88][89][90] The 15-LOX 1/13(S)-HODE axis also promotes the growth of prostate cancer in various animal models.[91][92] In one animal model the pro-growth effects of 15-LOX 1 were altered by dietary targeting: increases in dietary linoleic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid, promoted while increases in dietary stearidonic acid, an omega-3 fatty acid reduced the growth of human prostate cancer explants.[93] These effects could be due the ability of the linoleic acid diet to increase the production of the 15-Lox 1 metabolite, 13-HODE,[93] and the ability of the stearidonic acid to increase the production of docosahexaenoic acid and the 15-LOX-1 metabolites of docosahexaenoic acid, 17S-hydroperoxy-docosa-hexa-4Z,7Z,10Z,13 Z,15E,19Z-enoate(17-HpDHA, 17S-hydroxy-docosahexa-4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,15E,19Z-enoate(17-HDHA), 10S,17S-dihydroxy-docosahexa-4Z,7Z,11E,13Z,15E,19Z-enoate(10,17-diHDHA, protectin DX), and 7S,17S-dihydroxy-docsahexa-4Z,8E,10Z,13Z,15E,19Z-enoate(7,17-diHDHA, protectin D5), all of which are inhibitors of cultured human prostate cancer cell proliferation.[94][95][96]

Markers for disease

13-HODE levels are elevated, compared to appropriate controls, in the low density lipoproteins isolated from individuals with rheumatoid arthritis,[97] in the high-density lipoprotein fraction of patients with diabetes,[98] in the serum of individuals with polycystic kidney disease.[99] or chronic pancreatitis,[100] and in the plasma of individuals with alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.[101][102] The level of total HODEs, which includes various 13-HODE and 9-HODE isomers, are elevated in the plasma and erythrocytes of patients with Alzheimer's disease and in the plasma but not erythrocytes of patients with vascular dementia compared to normal volunteers.[103] See 9-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid section on 9-HODEs as markers of disease involving oxidative stress for further details. These studies suggest that high levels of the HODEs may be useful to indicate the presence and progression of the cited diseases. Since, however, the absolute values of HODEs found in different studies vary greatly, since HODE levels vary with dietary linoleic acid intake, since HODEs may form during the processing of tissues, and since abnormal HODE levels are not linked to a specific disease, the use of these metabolites as markers has not attained clinical usefulness.[23][104][105][106] HODE markers may find usefulness as markers of specific disease, type of disease, and/or progression of disease when combined with other disease markers.[107][108]

References

- 1 2 J Biol Chem. 1985 Apr 10;260(7):4508-15

- 1 2 Biochemistry. 2008 Jul 15;47(28):7364-75. doi: 10.1021/bi800550n

- ↑ Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989 Jun 15;161(2):883-91>

- ↑ Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993 Jul 21;1169(1):80-9

- ↑ Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002 Aug;68-69:263-90

- 1 2 3 J Biol Chem. 1990 Jan 25;265(3):1454-8

- ↑ J Biol Chem. 1998 Sep 4;273(36):23225-32

- ↑ Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Jun 10;94(12):6148-52

- ↑ Biochemistry. 2009 Sep 15;48(36):8721-30. doi: 10.1021/bi9009242

- ↑ J Biol Chem. 1995 Aug 18;270(33):19330-6

- ↑ J Invest Dermatol. 1996 Nov;107(5):726-32

- ↑ Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980 Mar 21;617(3):545-7

- ↑ J Invest Dermatol. 1996 Nov;107(5):726-32

- ↑ Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984 Aug 15;233(1):80-7

- ↑ Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993 Feb 24;1166(2-3):258-63

- ↑ Mol Pain. 2012 Sep 24;8:73. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-73

- ↑ Prog Lipid Res. 1984;23(4):197-221

- ↑ Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998 May 20;1392(1):23-40

- ↑ Chem Res Toxicol. 2005 Feb;18(2):349-56

- ↑ Free Radic Biol Med. 2015 Feb;79:164-75. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.12.004

- ↑ J Oleo Sci. 2015;64(4):347-56. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess14281

- ↑ Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Dec;299(6):E879-86. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00508.2010

- 1 2 Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2012 Oct-Nov;87(4-5):135-41. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.08.004

- ↑ J Oleo Sci. 2015;64(4):347-56. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess14281

- 1 2 J Lipid Res. 1994 Feb;35(2):255-62

- ↑ Arch Dermatol Res. 1993;285(8):449-54

- ↑ J Lipid Res. 1999 Apr;40(4):699-707

- ↑ Prostaglandins. 1991 Jan;41(1):43-50

- ↑ Carcinogenesis, 14 (11) (1993), pp. 2239–2243

- ↑ Biochim Biophys Acta, 1081 (2) (1991), pp. 174–180

- ↑ Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990 Jun;279(2):218-24

- ↑ Anal Biochem. 2001 May 15;292(2):234-44

- ↑ Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Nov 3;106(44):18820-4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905415106

- ↑ Biochem Pharmacol. 2007 Aug 15;74(4):612-22

- ↑ PLoS One. 2015 Jul 17;10(7):e0132042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132042. eCollection 2015

- ↑ Hepatology. 2012 Oct;56(4):1291-9. doi: 10.1002/hep.25778

- ↑ Hepatology. 2012 Oct;56(4):1291-9. doi: 10.1002/hep.25778

- ↑ Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002 Aug;68-69:471-82

- ↑ Life Sci. 1996;58(25):2355-65

- ↑ Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999 Sep 22;1440(2-3):225-34

- ↑ Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002 Aug;68-69:471-82

- 1 2 Cell. 1998 Apr 17;93(2):229-40

- ↑ Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008 Sep;15(9):924-31

- ↑ Biol Pharm Bull. 2009 Apr;32(4):735-40

- ↑ FEBS Lett. 2000 Apr 7;471(1):34-8

- ↑ Br J Pharmacol. 2012 Dec;167(8):1643-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02122.x

- ↑ Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Nov 3;106(44):18820-4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905415106

- ↑ Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009 Sep;89(3-4):66-72. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2008.11.002

- ↑ J Biol Chem. 2009 May 1;284(18):12328-38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806516200

- ↑ Nature. 1998 Sep 24;395(6700):392-5

- ↑ J Biol Chem. 1996 Sep 27;271(39):24055-62

- ↑ Gene. 2015 Jul 26. pii: S0378-1119(15)00914-2. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.07.073

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sci Rep. 2013;3:1349. doi: 10.1038/srep01349

- ↑ Prostaglandins. 1991 Jan;41(1):21-7

- ↑ Immunobiology. 2013 Jun;218(6):875-83. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.10.009

- ↑ J Exp Med. 1994 Jun 1;179(6):1903-11

- ↑ J Clin Invest. 1995;96(1):504-510. doi:10.1172/JCI118062

- ↑ Atherosclerosis. 2003 Mar;167(1):111-20

- ↑ J Clin Invest. 1997 Mar 1;99(5):888-93

- 1 2 Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014 Sep 15;307(6):G664-71. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00064.2014

- ↑ Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Aug;1(4):165-75. doi: 10.1177/2042018810381066

- ↑ Lipids. 2014 Dec;49(12):1181-92. doi: 10.1007/s11745-014-3954-z

- ↑ Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Aug;1(4):165-75. doi: 10.1177/2042018810381066

- ↑ Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Aug;1(4):165-75. doi: 10.1177/2042018810381066

- ↑ Lipids. 2014 Dec;49(12):1181-92. doi: 10.1007/s11745-014-3954-z

- ↑ J Clin Invest. 2000 Apr 15; 105(8): 1049–1056.

- ↑ Nat Med. 2001 Jun;7(6):699-705

- ↑ Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015 Jan 30;457(1):23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.063

- ↑ J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995 Jul;96(1):36-43

- 1 2 3 J Immunol. 2008 Sep 1;181(5):3540-8

- ↑ Sci Rep. 2013;3:1349. doi: 10.1038/srep01349>

- ↑ Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Oct;126(4):722-729.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.046.

- ↑ Prostaglandins. 1996 Aug;52(2):117-24

- ↑ Intern Med J. 2015 May;45(5):482-91. doi: 10.1111/imj.12736

- ↑ Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010 Jul;3(7):829-38. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0110

- 1 2 Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2013 Jul-Aug;104-105:139-43. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2012.08.004

- ↑ Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015 Apr;1851(4):308-330. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.002

- ↑ Carcinogenesis. 1999 Oct;20(10):1985-95

- ↑ Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004 Jan;70(1):7-15

- ↑ Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010 Jul;3(7):829-38. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0110. Epub 2010 Jun 22

- ↑ Carcinogenesis. 1999 Oct;20(10):1985-95.

- ↑ Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Aug 19;100(17):9968-73. Epub 2003 Aug 8

- ↑ Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004 Jan;70(1):7-15

- ↑ PLoS One. 2013 May 2;8(5):e63076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063076. Print 2013

- ↑ Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997 Feb 3;231(1):111-6

- ↑ J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2011 Sep;16(3):235-45. doi: 10.1007/s10911-011-9222-4

- ↑ PLoS One. 2013 May 2;8(5):e63076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063076. Print 2013

- ↑ Curr Urol Rep. 2002 Jun;3(3):207-14

- ↑ J Biol Chem. 2002 Oct 25;277(43):40549-56

- ↑ Neoplasia. 2004 Jan-Feb;6(1):41-52>

- ↑ Neoplasia. 2006 Jun;8(6):510-22

- ↑ Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2006 Oct;81(1-2):1-13

- 1 2 Neoplasia. 2009 Jul;11(7):692-9

- ↑ Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Dec 15;10(24):8275-83

- ↑ PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045480

- ↑ Hu Y, Sun H, O'Flaherty JT, Edwards IJ

- ↑ Chem Phys Lipids. 1997 May 30;87(1):81-9

- ↑ J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 May;100(5):2006-14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4214

- ↑ J Lipid Res. 2013 Dec 16;55(6):1139-1149

- ↑ Pancreas. 2012 May;41(4):518-22. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31823ca306

- ↑ J Biol Chem. 2010 Jul 16;285(29):22211-20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119982

- ↑ J Lipid Res. 2010 Oct;51(10):3046-54. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M007096

- ↑ Neurobiol Aging. 2009 Feb;30(2):174-85

- ↑ J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2013 Jan;52(1):9-16. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.12-112

- ↑ Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Feb;1840(2):809-17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.03.020

- ↑ J Oleo Sci. 2015;64(4):347-56. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess14281

- ↑ J Oleo Sci. 2015;64(4):347-56. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess14281

- ↑ Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014 Feb 24;6(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-25