1st Maryland Infantry, CSA

| 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA | |

|---|---|

|

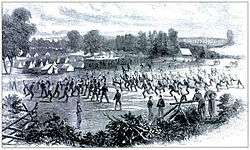

Camp Johnson, near Winchester, Virginia. This engraving shows the 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment "playing football before evening parade". Published in Harper's Weekly on August 31, 1861. The Marylanders wear uniforms received in May and June 1861 | |

| Active | April 1861 - August 1862 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Regiment |

| Size | One regiment |

| Engagements |

First Battle of Manassas Shenandoah Valley Campaign Peninsular Campaign. |

| Commanders | |

| Ceremonial chief | President of the Confederate States of America |

| Colonel of the Regiment |

Col. Francis J. Thomas (April 1861-June1861) |

The 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA was a regiment of the Confederate army, formed shortly after the commencement of the American Civil War in April 1861. The unit was made up of volunteers from Maryland who, despite their home state remaining in the Union during the war, chose instead to fight for the Confederacy. The regiment saw action at the First Battle of Manassas, in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, and in the Peninsular Campaign. It was mustered out of service in August 1862, its initial term of duty having expired. Many of its members, unable or unwilling to return to Union-occupied Maryland, went on to join a new regiment, the 2nd Maryland Infantry, CSA, which was formed in its place.

History

Baltimore riots of April 1861

After the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12–14, 1861, President Lincoln called for the states to send troops to preserve the Union. On April 19, Southern sympathizers in Baltimore attacked Union troops passing through by rail, causing what were arguably the first casualties of the Civil War. Major General George H. Steuart, commander of the Maryland State Militia, and most of his senior officers were strongly sympathetic to the Confederacy. He ordered the militia to turn out, armed and uniformed, to repel Federal soldiers.[1] Perhaps knowing of these sympathies, and that public opinion in Baltimore was divided, Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks did not order out the militia.[2]

Joining the Confederacy

During the early summer of 1861, several thousand Marylanders crossed the Potomac river to join the Confederate Army. Most of the men enlisted into regiments from Virginia or the Carolinas, but six companies of Marylanders formed at Harpers Ferry into the Maryland Battalion.[3] Among them were members of the former volunteer militia unit, the Maryland Guard Battalion, initially formed in Baltimore in 1859.[4]

Captain Bradley T. Johnson, commander of Company A., refused the offer of the Virginians to join a Virginia Regiment, insisting that Maryland should be represented independently in the Confederate army.[3] When the regiment was organised the first commander was Colonel Francis J. Thomas, a graduate of West Point in the class 1844. His choice as commander was vocally objected by several company commanders, and on June 8 he was relieved of command. It was agreed that Arnold Elzey, a seasoned career officer from Maryland, would take command. His executive officer was the Marylander George H. Steuart, who would later be known as "Maryland Steuart" to distinguish him from his more famous cavalry colleague JEB Stuart.[3]

The 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment was officially formed on June 16, 1861, and, on June 25, two additional companies joined the regiment in Winchester.[3] Its initial term of duty was for twelve months.

Civil War

In June 1861 General Johnston evacuated Harper's Ferry, and the 1st Maryland was ordered to assist in destroying its arsenal of weaponry.[3]

Battle of First Manassas

At the First Battle of Manassas, also known as the First Battle of Bull Run, on July 21, 1861, the 1st Maryland was combined with the 13th Virginia Infantry, 10th Virginia Infantry and 3rd Tennessee Regiments to form the 4th Brigade, led by Brigadier General E. Kirby Smith. Smith's men were late in arriving at the battle and approached the Confederate left near Chinn Ridge. The battle got off to a bad start when Elzey was forced to assume temporary command of the brigade, as General Smith was shot from his horse and injured by enemy fire. However, Elzey was able to bring his men into line facing the flank of the Federal army, the brigade commanded by General Oliver O. Howard. His men advanced to the edge of a wood without being detected by the Union army and opened fire, after which they charged over open ground into the Union position. Soon they were joined by Colonel Jubal A. Early on the Confederate left flank and shortly afterwards Howard's line began to disintegrate. As the federal forces fled, General Beauregard congratulated Elzey, commending him as "the Blucher of the day".[3]

After the battle Elzey was promoted to Brigade Commander, and Colonel George H. Steuart was given command of the 1st Maryland Regiment. Major Bradley Johnson was appointed his second in command.[3]

During the winter of 1861-2 the regiment was quartered at Centerville. In April 1862 it was marched back to the Rappahannock River, and assigned to the command of General Richard S. Ewell, following which the regiment joined General "Stonewall" Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley, meeting him at Luray, Virginia. At this point an unsuccessful attempt was made to form a "Maryland Line" in the CSA, uniting all Maryland units under one command.[3]

Training and discipline

Under Steuart's command the regiment was drilled relentlessly. Steuart soon began to acquire a reputation as a strict disciplinarian, eventually gaining the admiration of his men,[5] though initially unpopular as a result. Steuart was said to have ordered his men to sweep the bare dirt inside their bivouacs and, rather more eccentrically, was prone to sneaking through the lines past unwitting sentries, in order to test their vigilance.[6] On one occasion this plan backfired, as Steuart was pummeled and beaten by a sentry who later claimed not to have recognized the general.[7] Eventually however, Steuart's "rigid system of discipline quietly and quickly conduced to the health and morale of this splendid command."[8] According to Major W W Goldsborough, who served under Steuart at Gettysburg: "...it was not only his love for a clean camp, but a desire to promote the health and comfort of his men that made him unyielding in the enforcement of sanitary rules. You might influence him in some things, but never in this".[9] George Wilson Booth, a young officer in Steuart's command at Harper's Ferry in 1861, recalled in his memoirs: "The Regiment, under his master hand, soon gave evidence of the soldierly qualities which made it the pride of the army and placed the fame of Maryland in the very foreground of the Southern States".[10]

Shenandoah campaign and the expiry of the regiment's term of duty

On May 17 the initial 12-month term of duty of C Company expired, and the men began to clamor for their immediate discharge. By this time Steuart had been promoted brigadier general, assigned with the task of forming the Maryland Line, and Colonel Bradley Tyler Johnson had succeeded to command of the regiment. Johnson reluctantly agreed with the men, but could not disband the entire regiment in mid-campaign, and discontent began to spread.[12] By May 22, on the eve of the Battle of Front Royal, discontent became open mutiny. Steuart and Johnson argued with the men to no avail, though news of the rebellion was kept secret from General Jackson. When given orders to engage the enemy, Johnson addressed his soldiers:

- "You have heard the order, and I must confess are in a pretty condition to obey it. I will have to return it with the endorsement upon the back that 'the First Maryland refuses to meet the enemy', despite being given orders by General Jackson. Before this day I was proud to call myself a Marylander, but now, God knows, I would rather be known as anything else. Shame on you to bring this stigma upon the fair name of your native state - to cause the finger of scorn to be pointed at those who confided to your keeping their most sacred trust - their honor and that of the glorious Old State. Marylanders you call yourselves - profane not that hallowed name again, for it is not yours. What Marylander ever before threw down his arms and deserted his colors in the presence of the enemy, and those arms, and those colors too, placed in your hands by a woman? Never before has one single blot defaced her honored history. Could it be possible to conceive a crime more atrocious, an outrage more damnable? Go home and publish to the world your infamy. Boast of it when you meet your fathers and mothers, brothers, sisters and sweethearts. Tell them it was you who, when brought face to face with the enemy, proved yourselves recreants, and acknowledged yourselves to be cowards. Tell them this, and see if you are not spurned from their presence like some loathsome leper, and despised, detested, nay abhorred, by those whose confidence you have so shamefully betrayed; you will wander over the face of the earth with the brand of 'coward', 'traitor', indelibly imprinted on your foreheards, and in the end sink into a dishonored grave, unwept for, uncared for, leaving behind as a heritage to your posterity the scorn and contempt of every honest man and virtuous woman in the land."

Johnson's speech seems to have worked where threats had failed, and the Marylanders rallied to the regimental colors, seizing their weapons and crying "lead us to the enemy and we will prove to you that we are not cowards"[13]

Battle of Front Royal

At the Battle of Front Royal, May 23, 1862, the 1st Maryland was thrown into battle with their fellow Marylanders, the Union 1st Regiment Maryland Volunteer Infantry.[3] This is the only time in United States military history that two regiments of the same numerical designation and from the same state have engaged each other in battle. After hours of desperate fighting the Southerners emerged victorious. When the prisoners were taken, many men recognized former friends and family. According to Goldsborough:

- "nearly all recognized old friends and acquaintances, whom they greeted cordially, and divided with them the rations which had just changed hands".[14]

Among the prisoners was Charles Goldsborough, captured by his brother, William Goldsborough, who would go on to write the history of the Maryland Line in the Confederate Army.[15]

Battle of Winchester

Just two days later, on May 25, 1862, the 1st Maryland fought again at the First Battle of Winchester, another Confederate victory. After the battle, Colonel Johnson, who was described by Goldsborough as "one of the handsomest men in the First Maryland", was the recipient of some not entirely welcome female attention:

- "having dismounted from his horse in an unguarded moment, [Col. Johnson] was espied and singled out by an old lady of Amazonian proportions, just from the wash tub, who, wiping her hands and mouth on her apron as she approached, seized him around the neck with the hug of a bruin, and bestowed upon him half a dozen kisses that were heard by nearly every man in the command, and when at length she relaxed her hold the Colonel looked as if he had just come out a vapor bath".[11]

Battle of Cross Keys

The unit again saw action at the Battle of Cross Keys on June 8, where the 1st Maryland were placed on General Ewell's left, successfully fighting off three assaults by Federal troops.[3] At Cross Keys George H. Steuart, was severely injured in the shoulder by grape shot, and had to be carried from the battlefield.[16] A ball from a canister shot had struck him in the shoulder and broken his collarbone, causing a "ghastly wound".[16] The injury did not heal well, and did not begin to improve at all until the ball was removed under surgery in August. It would prevent him from returning to the field for almost an entire year, until May 1863.[17]

Peninsula Campaign

On June 26 the 1st Maryland fought at the Battle of Gaines' Mill where the regiment held off an assault by Federal infantry until the Baltimore Light Artillery could be wheeled into place to dislodge the Federal troops. They saw action the next day when they participated in an attack which captured a number of guns, weapons and many prisoners.[3]

The regiment also saw action on 1 July 1862 at the Battle of Malvern Hill, this time a Union victory. The regiment was held in reserve, but still suffered severe casualties from the heavy barrage of the Federal artillery. On July 2 they fought off a Federal cavalry attack in a brief skirmish.[3]

Disbandment

By late summer the Southern capital of Richmond, Virginia was considered safe from Federal attack, and the Regiment's one-year term of duty having expired, it was soon disbanded.[18] Company A. was assigned to escort duty, bringing General Jackson's prisoners to Richmond, and soon after this it was mustered out of service. On August 17 the rest of the regiment was also disbanded at Gordonsville, Virginia. In September 1862 the regiment's former commander, Colonel Bradley Tyler Johnson, and many members of his staff, finding themselves without a command, offered their services to General "Stonewall Jackson".[3]

However, the soldiers of the disbanded regiment found themselves in a precarious position, being unable to return home to Union-occupied Maryland, having effectively committed themselves to the Confederacy for the duration of the war. With little choice but to fight on, many went on to join other units of artillery, or cavalry, while others waited to form a new Maryland Infantry Regiment, which would become known as the 2nd Maryland Infantry, CSA in order to distinguish it from the original regiment.[3] The new regiment would suffer such severe casualties during the course of the war that, by the time of General Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, only around forty men remained.

See also

- History of the Maryland Militia in the Civil War

- Maryland in the American Civil War

- Maryland Civil War Confederate units

- Maryland Line (CSA)

References

- Andrews, Matthew Page, History of Maryland, Doubleday, New York (1929)

- Booth, George W., Personal Reminiscences of a Maryland Soldier in the War Between the States, 1861-1865. Lincoln, NE: U NE press, 2000 reprint of 1898 ed.

- Ernst, Kathleen. Accompanied by Cries of 'Go It, Boys! Maryland Whip Maryland! Two 1st Marland Infantries Clashed. America's CW (Jul 1994: pp. 10, 12, 14 & 16.

- Field, Ron, et al., The Confederate Army 1861-65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved March 4, 2010

- Goldsborough, W.W., p. 285-91, Grant's Change of Base: The Horrors of the Battle of Cold Harbor, From a Soldier's Notebook. Southern Hist Soc Papers 29 (1901)

- Goldsborough, W. W., The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, Guggenheimer Weil & Co (1900), ISBN 0-913419-00-1.

- Green, Ralph, Sidelights and Lighter Sides of the War Between the States, Burd St Press (2007), ISBN 1-57249-394-1.

- Howard, McHenry. Recollections of a Maryland Confederate Soldier and Staff Officer Under Johnston, Jackson and Lee. Dayton, OH: Morningside, 1975. Reprint of 1914 ed.

- Johnson, Bradley T. The Cause of the Confederate States: Address Delivered Before the Society of the Army and Navy of the Confederate States, in the State of Maryland, and the Association of the Maryland Line, at Maryland Hall, Baltimore, Md., November l6th, 1886. Baltimore: A.J. Conlon, 1886.

- McKim, Randolph H. A Soldier's Recollections: Leaves From the Diary of a Young Confederate. NY: Longmans, Green, 1911.

- Swank, Walbrook D. Courier for Lee and Jackson: 1861-1865-Memoirs. [John Gill] Shippensburg, MD: White Mane, 1993.

- Wilmer, L. Allison; J. H. Jarrett; Geo. W. F. Vernon (1899). History and Roster of Maryland Volunteers, War of 1861-5, Volume 1. Baltimore: Guggenheimer, Weil, & Co. pp. 71–72.

- Tagg, Larry, The Generals of Gettysburg, Savas Publishing (1998), ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

Archival Collections

- Civil War Memoirs of Washington Hands - served in 1st Maryland Infantry, and in the Baltimore Light Artillery. University of Virginia Library, Special Collections Department, Alderman Library, Charlottesville, VA.

- Bradley T. Johnson Papers, University of Virginia Library, Special Collections Department, Alderman Library, Charlottesville, Virginia.

- Muster Roll of 1st Maryland Infantry, Fray Angelico Chavez History Library, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

- Photographs of unit members, Photo Collection, USAMHI, Carlisle, PA

- Selvage, Edwin HCWRTCollGACColl, USAHMI, Carlisle, PA

Notes

- ↑ Hartzler, Daniel D., A Band of Brothers: Photographic Epilogue to Marylanders in the Confederacy, p. 13. Retrieved March 1, 2010

- ↑ Brugger, Robert J. Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980, p. 285. Johns Hopkins University Press (1996) Retrieved May 10, 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Maryland Civil War units at www.2ndmdinfantryus.org/csunits.html Retrieved May 10, 2010

- ↑ Field, Ron, et al., The Confederate Army 1861-65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved March 4, 2010

- ↑ Goldsborough, p.30.

- ↑ Tagg, p.273.

- ↑ Green, p.125.

- ↑ Article on Steuart at stonewall.hut.ru Retrieved May 13, 2010

- ↑ Goldsborough, p.119

- ↑ Booth, George Wilson, p.12, A Maryland Boy in Lee's Army: Personal Reminiscences of a Maryland Soldier in the War Between the States, Bison Books (2000). Retrieved Jan 16 2010

- 1 2 Goldsborough, J. J., p.59, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army Retrieved May 13, 2010

- ↑ Goldsborough, J. J., p.44, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army Retrieved May 13, 2010

- ↑ Goldsborough, J. J., p.49, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army Retrieved May 13, 2010

- ↑ Goldsborough, J. J., p.58, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army Retrieved May 13, 2010

- ↑ Goldsborough, W.W., Introduction, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, Butternut Press, Maryland (1983)

- 1 2 Goldsborough, p.56.

- ↑ Tagg, p.273

- ↑ Andrews, p.544

External links

- The Maryland line in the Confederate States Army. Published by Gale Cengage Learning, ISBN 1-4328-1267-X, 9781432812676 Retrieved February 20, 2010

- Maryland Civil War units at www.2ndmdinfantryus.org/csunits.html Retrieved February 20, 2010

- Re-enactment society of the 1st Maryland Infantry Retrieved May 10, 2010