25th Hour

| 25th Hour | |

|---|---|

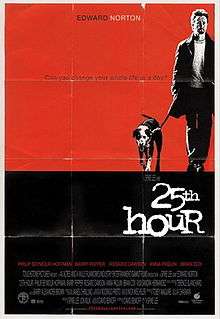

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Spike Lee |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | David Benioff |

| Based on |

The 25th Hour by David Benioff |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Terence Blanchard |

| Cinematography | Rodrigo Prieto |

| Edited by | Barry Alexander Brown |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 134 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5 million[2] |

| Box office | $23.9 million[2] |

25th Hour is a 2002 American drama film directed by Spike Lee and starring Edward Norton. Based on the novel The 25th Hour by David Benioff, who also wrote the screenplay, it tells the story of a man's last 24 hours of freedom as he prepares to go to prison for seven years for dealing drugs.

25th Hour opened to positive reviews, with several critics since having named it one of the best films of its decade.

Plot

A canary yellow vintage Super Bee pulls up short on a New York City street, and Montgomery "Monty" Brogan gets out with his buddy Kostya to look at a dog lying in the road. The animal was mauled in a dogfight so Monty intends to shoot him, but changes his mind after he looks it in the eye. Monty decides to take the dog to a nearby clinic instead.

Fast forward to late 2002. Monty is about to begin serving a seven-year prison sentence for dealing drugs. He sits in a park with Doyle, the dog he rescued, on his last day of freedom. He plans to meet childhood friends Frank Slaughtery and Jacob Elinsky at a club with his girlfriend Naturelle. Frank is a hotshot trader on Wall Street; Jacob is an introverted high school teacher with a crush on 17-year-old Mary, one of his students.

Monty visits his father, James, a former firefighter and recovering alcoholic who owns a bar, to confirm their plans to drive to the prison the following morning. Monty's drug money helped James keep the bar, so a remorseful James sneaks a drink when Monty goes to the bathroom. Facing himself in the mirror, Monty lashes out in his mind against everyone else: all the New York stereotypes he can think of, from the cabbies to the firefighters, the corner grocers to the mobsters, as if he hates them all. Finally, he turns on himself, revealing that he is actually angry for getting greedy and having not given up drug dealing before he was caught.

In a flashback, Monty remembers the night he was arrested. Detectives come to Monty's apartment while he's still there. They find the drugs immediately and not after any real search, suggesting that Monty had been betrayed. Monty sold drugs for Uncle Nikolai, a Russian mobster. Kostya tries to persuade Monty it was Naturelle who turned him in, since she knew where he hid his drugs and money. Monty refused to turn state's evidence against Nikolai, but he's not sure what Nikolai will do at the club that night. Monty remembers how he met Naturelle when she was 18, hanging around his old school, and how happy they were. He asks Frank to find out if it was Naturelle who betrayed him.

Jacob sees Mary outside the club, so Monty invites her inside with them. Discussing what kind of a future Monty can have after prison, Frank says they can open a bar together, even though he told Jacob he believes Monty's life is over, and that Monty deserves his sentence for dealing drugs. Frank accuses Naturelle of living high on Monty's money, not caring where it came from, but she reminds Frank that he knew as well and said nothing. The argument culminates in Frank's insulting Naturelle's ethnicity, followed by her slapping Frank and leaving. Jacob, meanwhile, finds the courage to kiss Mary, but both appear to be in shock afterwards and go their separate ways.

Monty and Kostya go see Uncle Nikolai, who gives Monty advice on surviving in prison. Nikolai then reveals it was Kostya, not Naturelle, who betrayed Monty, and offers him a chance to kill Kostya in exchange for protecting his father's bar. Monty refuses, reminding Nikolai that he had asked Monty to trust Kostya in the first place. Monty walks out, leaving Kostya to be killed by the Russian mobsters.

Monty returns to his apartment and apologizes to Naturelle for mistrusting her. At the park, he transfers custody of Doyle to Jacob. Then he admits that he is terrified of being raped in prison, whereupon he asks Frank to brutally beat him, saying if he goes in ugly he might have a chance at survival. Frank refuses, so Monty deliberately provokes him. Frank is goaded into taking out his frustration, leaving Monty bruised and bloody, with a broken nose. Frank is in tears as Monty gets up and goes home.

Naturelle tries to comfort him as Monty's father arrives to take him to Federal Correctional Institution, Otisville. On the drive to prison, James suggests they go west, into hiding, giving Monty one last vision of freedom. Once again Monty sees a parade of faces from the streets of the city, followed by a vision of a future where Monty avoids imprisonment, reunites with Naturelle, starts a family, and grows old. As the fantasy ends, we see Monty, his eyes closed and face still bruised, sitting in the passenger's seat of the car, which has driven past the bridge to the west and towards prison.

Cast

- Edward Norton as Montgomery "Monty" Brogan

- Philip Seymour Hoffman as Jacob Elinsky

- Barry Pepper as Frank Slaugherty

- Rosario Dawson as Naturelle Riviera

- Anna Paquin as Mary D'Annunzio

- Brian Cox as James Brogan

- Tony Siragusa as Kostya Novotny

- Levan Uchaneishvili as Uncle Nikolai

- Tony Devon as Agent Allen

- Misha Kuznetsov as Senka Valghobek

- Isiah Whitlock, Jr. as Agent Flood

- Michael Genet as Agent Cunningham

- Patrice O'Neal as Khari

- Al Palagonia as Salvatore Dominick

- Aaron Stanford as Marcuse

- Marc H. Simon as Schultz

- Armando Riesco as Phelan

Writing and production

Benioff completed the book The 25th Hour while studying at the University of California Irvine,[3][4] which was published in 2001. Six months before the book's publication, a preliminary trade copy was circulated, which Tobey Maguire read and he was interested in playing the role of Monty Brogan. He acquired the option for a potential film project and asked Benioff to adapt it into a screenplay.[5][4] However, after the script was written, Maguire became pre-occupied with the Spider-Man film and had to abandon the plan, although he would later act as a producer on the film that was made. Spike Lee then expressed an interest in directing the film.[4][6] A long monologue that Benioff called the "fuck monologue" whereby Monty ranted against the five boroughs of New York and all their major ethnic groups was initially cut, but Spike Lee wanted it re-instated. Disney picked up the film rights but also wanted the monologue cut, but Lee filmed the scene nonetheless.[4]

The film was in the "planning stages" at the time of the September 11 attacks, and so Lee "decided not to ignore the tragedy but to integrate it into his story".[7]

Reception

25th Hour received a 78% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 166 reviews.[8] The film also holds a 67/100 score on Metacritic.[9]

Five years after the September 11 attacks, Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote: "Released 15 months after Sept. 11, 2001, Spike Lee's 25th Hour is the only great film dealing with the Sept. 11 tragedy... 25th Hour is as much an urban historical document as Rossellini's Open City, filmed in the immediate aftermath of the Nazi occupation of Rome".[7]

Film critic Roger Ebert added the film to his "Great Movies" list on December 16, 2009.[10] A. O. Scott,[11] Richard Roeper[12] and Roger Ebert all put it on their "best films of the decade" lists.[13] It was later named the 26th greatest film since 2000 in a BBC poll of 177 critics.[14]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[15]

Music

Terence Blanchard composed the film's musical score. Other songs that appear in the film (and are not included in the original score) include:

- Big Daddy Kane – "Warm It Up, Kane"

- Craig Mack – "Flava in Ya Ear"

- The Olympic Runners – "Put the Music Where Your Mouth Is"

- Grandmaster Melle Mel – "White Lines (Don't Don't Do It)"

- Liquid Liquid – "Cavern"

- Cymande – "Bra"

- Cymande – "Dove"

- Cymande – "The Message"

- Bruce Springsteen – "The Fuse"

In popular culture

- Better Call Saul season 1, episode 7 ("Bingo") makes both visual and verbal references to this film and its source novel, as well as to The Simpsons. Jimmy tells Kim to “Picture The 25th Hour, starring Ned and Maude Flanders”, when he phones Kim to tell her the Kettlemans, one of whom is facing jail time, have hired him to replace Kim as their attorney. The Kettlemans had hoped to avoid taking Kim's deal, but Jim forces their hand by turning over to the D.A. all of the embezzled funds, including the $30,000 "retainer" the Kettlemans had bribed him with. Returning the money forces Jimmy, who - with echoes of the canary yellow bus in the film 25th Hour - drives a canary yellow jalopy and must forego renting the upscale office he had planned to use the $30,000 to pay for and in which he had hoped to entice Kim to come work with him. In the last scene, Jimmy leans dejectedly against a cross-shaped pair of beams in that canary yellow office, which he had hoped represented his ticket out of squalor, knowing he must return to his cell-like office space in the boiler room of a nail salon.[16][17][18]

See also

References

- ↑ "25th Hour (15)". British Board of Film Classification. January 31, 2003. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- 1 2 "25th Hour (2002)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Crowning achievement". UCI News. August 12, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Benioff, David (May 3, 2003). "One more hour". The Guardian.

- ↑ Katie Kilkenny (May 12, 2011). "Benioff '92 embraces storytelling in 'surreal' career". The Dartmouth.

- ↑ "Q: What do Brad Pitt, Spike Lee and the Iliad have in common? A: David Benioff, Hollywood's latest wonder kid". Herald Scotland. March 29, 2003.

- 1 2 "9/11: FIVE YEARS LATER: Spike Lee's '25th Hour'". San Francisco Chronicle. June 10, 2013.

- ↑ "25th Hour (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixter. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ↑ "25th Hour (2002)". Metacritic.com. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (December 16, 2009). "25th Hour Review". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ↑ Dunn, Brian (December 26, 2009). "A. O. Scott's Ten Best Films of the 2000s". Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ↑ Roeper, Richard (January 1, 2010). "Roeper's best films of the decade". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (December 30, 2009). "The best films of the decade". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ↑ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- ↑ Bowman, Donna (March 16, 2015). "Better Call Saul, 'Bingo'". AV Club.

- ↑ Vine, Richard. "Better Call Saul recap: season one, episode seven – Bingo". The Guardian.

- ↑ Sepinwall, Alan (March 16, 2015). "Jimmy tries to do the right thing by Kim, and suffers for it". Hitfix.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: 25th Hour |