AFL–CIO

| |

| Full name | American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations |

|---|---|

| Founded | December 4, 1955 |

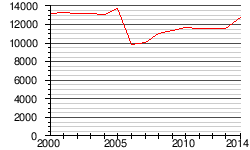

| Members | 12,741,859 (2014)[1] |

| Affiliation | ITUC |

| Key people | Richard Trumka, president[2] |

| Office location | Washington, D.C. |

| Country | United States |

| Website |

aflcio |

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO) is a national trade union center and the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of fifty-six national and international unions,[3] together representing more than 12 million active and retired workers.[1] The AFL–CIO engages in substantial political spending and activism.[3]

The AFL–CIO was formed in 1955 when the AFL and the CIO merged after a long estrangement. Membership in the union peaked in 1979, when the AFL–CIO had nearly twenty million members.[4] From 1955 until 2005, the AFL–CIO's member unions represented nearly all unionized workers in the United States. Several large unions split away from AFL–CIO and formed the rival Change to Win Federation in 2005, although a number of those unions have since re-affiliated. The largest union currently in the AFL–CIO is the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), with approximately 1.4 million members.[5]

Membership

The AFL–CIO is a federation of international labor unions. As a voluntary federation, the AFL–CIO has little authority over the affairs of its member unions except in extremely limited cases (such as the ability to expel a member union for corruption[7] and enforce resolution of disagreements over jurisdiction or organizing). As of June 2014, the AFL–CIO had 56 member unions representing 12.5 million members.[3]

Political activities

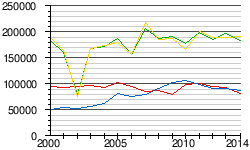

The AFL–CIO was a major component of the New Deal Coalition that dominated politics into the mid-1960s.[8] Although it has lost membership, finances, and political clout since 1970, it remains a major player on the liberal side of national politics, with a great deal of activity in lobbying, grassroots organizing, coordinating with other liberal organizations, fund-raising, and recruiting and supporting candidates around the country.[9]

In recent years the AFL–CIO has concentrated its political efforts on lobbying in Washington and the state capitals, and on "GOTV" (get-out-the-vote) campaigns in major elections. For example, in the 2010 midterm elections, it sent 28.6 million pieces of mail. Members received a "slate card" with a list of union endorsements matched to the member's congressional district, along with a "personalized" letter from President Trumka emphasizing the importance of voting. In addition, 100,000 volunteers went door-to-door to promote endorsed candidates to 13 million union voters in 32 states.[10][11]

The AFL–CIO gave $6,123,437 to super PACs in 2012, including $5.95 million to the AFL–CIO's own super PAC.[12]

In June 2016, it was reported that the AFL–CIO planned to endorse Hillary Clinton in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.[13]

Governance

The AFL–CIO is governed by its members, who meet in a quadrennial convention. Each member union elects delegates, based on proportional representation. The AFL–CIO's state federations, central and local labor councils, constitutional departments, and constituent groups are also entitled to delegates. The delegates elect officers and vice presidents, debate and approve policy, and set dues.[14]

- Executive council

The AFL–CIO has three executive officers: president, secretary-treasurer and executive vice president. Each officer's term is four years, and elections occur at the quadrennial convention.[15] Current officers are Richard Trumka (President), Liz Shuler (Secretary-Treasurer) and Tefere Gebre (Executive Vice-President).

The AFL–CIO membership elects 43 vice presidents at each convention, who have a term of four years. The AFL–CIO constitution permits the president of the federation to appoint up to three additional vice presidents during the period when the convention is not in session.

- Annual meetings

From 1951 to 1996, the Executive Council held its winter meeting in the resort town of Bal Harbour, Florida.[16] The meeting at the Bal Harbour Sheraton has been the object of frequent criticism, including over a labor dispute at the hotel itself.[17][18][19]

Citing image concerns, the council changed the meeting site to Los Angeles.[20][21] However, the meeting was moved back to Bal Harbour several years later.[22] The 2012 meeting was held in Orlando, Florida.[23]

- Executive committee

An executive committee was authorized by constitutional change in 2005. The executive committee is composed of the president, vice presidents from the 10 largest affiliates, and nine other vice presidents chosen in consultation with the executive council. The other two officers are non-voting ex officio members. The executive committee governs the AFL–CIO between meetings of the executive council, approves its budget, and issues charters (two duties formerly discharged by the executive council). It is required to meet at least four times a year, and in practice meets on an as-needed basis (which may mean once a month or more).

- General Board

The AFL–CIO also has a General Board. Its members are the AFL–CIO executive council, the chief executive officer of each member union, the president of each AFL–CIO constitutional department, and four regional representatives elected by the AFL–CIO's state federations. The General Board's duties are very limited. It only takes up matters referred to it by the executive council, but referrals are rare. However, because of the sensitive nature of political endorsements and the advisability of consensus when making them, the General Board traditionally is the body that provides the AFL–CIO's endorsement of candidates for president and vice president of the United States.

- State and local bodies

Article XIV of the AFL–CIO constitution permits the AFL–CIO to charter and organize state, regional, local and city-wide bodies. They are commonly called "state federations" and "central labor councils" (CLCs), although the names of the various bodies varies widely at the local and regional level. Each body has its own charter, which establishes its jurisdiction, governance structure, mission, and more. Jurisdiction tends to be geo-political: Each state or territory has its own "state federation." In large cities, there is usually a CLC covering the city. Outside large cities, CLCs tend to be regional (to achieve an economy of scale in terms of dues, administrative effectiveness, etc.). State federations and CLCs are each entitled to representation and voting rights at the quadrennial convention.

The duties of state federations differ from those of CLCs. State federations tend to focus on state legislative lobbying, statewide economic policy, state elections, and other issues of a more overarching nature. CLCs tend to focus on county or city lobbying, city or county elections, county or city zoning and other economic issues, and more local needs.

Both state federations and CLCs work to mobilize members around organizing campaigns, collective bargaining campaigns, electoral politics, lobbying (most often rallies and demonstrations), strikes, picketing, boycotts, and similar activities.

The AFL–CIO constitution permits international unions to pay state federation and CLC dues directly, rather than have each local or state federation pay them. This relieves each union's state and local affiliates of the administrative duty of assessing, collecting and paying the dues. International unions assess the AFL–CIO dues themselves, and collect them on top of their own dues-generating mechanisms or simply pay them out of the dues the international collects. But not all international unions pay their required state federation and CLC dues.[24]

- Constitutional departments

Throughout its history, the AFL–CIO had a number of constitutionally mandated departments. Initially, the rationale for having them was that affiliates felt that such decisions should not be left to the whims (or political needs) of the president of the federation.

Currently, Art. XII establishes seven departments, but allows the executive council or convention of the AFL–CIO to establish others. Each department is largely autonomous, but its must conform to the AFL–CIO's constitution and policies. Each department has its own constitution, membership, officers, governance structure, dues and organizational structure. Departments may establish state and local bodies. Any member union of the AFL–CIO may join a department, provided it formally affiliates and pays dues. The chief executive officer of each department may sit in on the meetings of the AFL–CIO executive council. Departments have representation and voting rights at the AFl–CIO convention.

One of the most well-known departments was the Industrial Union Department (IUD). It had been constitutionally mandated by the new AFL–CIO constitution created by the merger of the AFL and CIO in 1955, as CIO unions felt that the AFL's commitment to industrial unionism was not strong enough to permit the department to survive without a constitutional mandate. For many years, the IUD was a de facto organizing department in the AFL–CIO. For example, it provided money to the near-destitute American Federation of Teachers (AFT) as it attempted to organize the United Federation of Teachers in 1961. The organizing money enabled the AFT to win the election and establish its first large collective bargaining affiliate. For many years, the IUD remained rather militant on a number of issues. It proved to be a center of opposition to AFL–CIO president John Sweeney, and was abolished in 1999.

There are six AFL–CIO constitutionally mandated departments:

- Building and Construction Trades Department, AFL–CIO

- Maritime Trades Department, AFL–CIO

- Metal Trades Department, AFL–CIO

- Department for Professional Employees, AFL–CIO

- Transportation Trades Department, AFL–CIO

- Union Label Department, AFL–CIO

Constituency groups

Constituency groups are nonprofit organizations chartered and funded by the AFL–CIO as voter registration and mobilization bodies. These groups conduct research, host training and educational conferences, issue research reports and publications, lobby for legislation and build coalitions with local groups. Each constituency group has the right to sit in on AFL–CIO executive council meetings, and to exercise representational and voting rights at AFL–CIO conventions.

The AFL–CIO's seven constituency groups include the A. Philip Randolph Institute, the AFL–CIO Union Veterans Council, the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance, the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, the Coalition of Labor Union Women, the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement and Pride at Work.

Allied organizations

The Working for America Institute started out as a department of the AFL–CIO. Established in 1958, it was previously known as the Human Resources Development Institute (HRDI). John Sweeney renamed the department and spun it off as an independent organization in 1998 to act as a lobbying group to promote economic development, develop new economic policies, and lobby Congress on economic policy.[25] The American Center for International Labor Solidarity started out as the Free Trade Union Committee (FTUC), which internationally promoted free labor-unions.[26]

Other organizations that are allied with the AFL–CIO include:

- Alliance for Retired Americans

- Solidarity Center

- American Rights at Work

- International Labor Communications Association

- Jobs with Justice

- Labor Heritage Foundation

- Labor and Working-Class History Association

- National Day Laborer Organizing Network

- United Students Against Sweatshops

- Working America

- Working for America Institute

- Ohio Organizing Collaborative

Programs

Programs are organizations established and controlled by the AFL–CIO to serve certain organizational goals. Programs of the AFL–CIO include the AFL–CIO Building Investment Trust, the AFL–CIO Employees Federal Credit Union, the AFL–CIO Housing Investment Trust, the National Labor College and Union Privilege.

International policy

The AFL–CIO is affiliated to the Brussels-based International Trade Union Confederation, formed November 1, 2006. The new body incorporated the member organizations of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, of which the AFL–CIO had long been part. The AFL–CIO had had a very active foreign policy in building and strengthening free trade unions. During the Cold War it vigorously opposed Communist unions in Latin America and Europe. In opposing Communism it helped split the CGT in France and helped create the anti-Communist Force Ouvriere.[27]

History

For the history of the AFL–CIO prior to and including the merger see American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations and Labor unions in the United States.

Civil rights

The AFL–CIO has a long relationship with civil rights struggles. One of the major points of contention between the AFL and the CIO, particularly in the era immediately after the CIO split off, was the CIO's willingness to include black workers (excluded by the AFL in its focus on craft unionism.)[28][29][30] Later, blacks would also criticize the CIO for abandoning their interests, particularly after the merger with the AFL.[31]

In 1961, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave a speech titled "If the Negro Wins, Labor Wins" to the organization's convention in Bal Harbour, Florida. King hoped for a coalition between civil rights and labor that would improve the situation for the entire working class by ending white supremacy. However, King also criticized the AFL–CIO for its tolerance of unions that excluded black workers.[32] King and the AFL–CIO diverged further in 1967, when King announced his opposition to the Vietnam War, which the AFL–CIO strongly supported.[33] The AFL–CIO endorsed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[34]

New Unity Partnership

In 2003, the AFL–CIO began an intense internal debate over the future of the labor movement in the United States with the creation of the New Unity Partnership (NUP), a loose coalition of some of the AFL–CIO's largest unions. This debate intensified in 2004, after the defeat of labor-backed candidate John Kerry in the November 2004 U.S. presidential election. The NUP's program for reform of the federation included reduction of the central bureaucracy, more money spent on organizing new members rather than on electoral politics, and a restructuring of unions and locals, eliminating some smaller locals and focusing more along the lines of industrial unionism.

In 2005, the NUP dissolved and the Change to Win Federation (CtW) formed, threatening to secede from the AFL–CIO if its demands for major reorganization were not met. As the AFL–CIO prepared for its 50th anniversary convention in late July, three of the federations' four largest unions announced their withdrawal from the federation: the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the International Brotherhood of Teamsters ("The Teamsters"),[35] and the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW).[36] UNITE HERE disaffiliated in mid-September 2005,[37] the United Farm Workers left in January 2006,[38] and the Laborers' International Union of North America disaffiliated on June 1, 2006.[39]

Two unions later left CtW and rejoined the AFL–CIO. After a bitter internal leadership dispute that involved allegations of embezzlement and accusations that SEIU was attempting to raid the union,[40] a substantial number of UNITE HERE members formed their own union (Workers United) while the remainder of UNITE HERE reaffiliated with the AFL–CIO on September 17, 2009.[41] The Laborers' International Union of North America said on August 13, 2010, that it would also leave Change to Win and rejoin the AFL–CIO in October 2010.[42]

ILWU disaffiliation

In August 2013, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) disaffiliated from the AFL–CIO. The ILWU said that members of other AFL–CIO unions were crossing its picket lines, and the AFL–CIO had done nothing to stop it. The ILWU also cited the AFL–CIO's willingness to compromise on key policies such as labor law reform, immigration reform, and health care reform. The longshoremen's union said it would become an independent union.[43]

Presidents

- George Meany (1955–1979)

- Lane Kirkland (1979–1995)

- Thomas R. Donahue (1995)

- John J. Sweeney (1995–2009)

- Richard Trumka (2009- )

See also

- Change to Win Federation

- Directly Affiliated Local Union (DALU)

- Labor federation competition in the U.S.

- Labor movement

- Labor unions in the United States

- List of unions affiliated with the AFL–CIO

- List of U.S. trade unions

- Union organizer

References

- 1 2 US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-106. Report submitted September 26, 2014.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Steven. "Promising a New Day, Again." New York Times. September 15, 2009; Greenhouse, Steven. "Labor Leader Is Stepping Down Both Proud and Frustrated." New York Times. September 12, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "AFL–CIO". FactCheck.org. Annenberg Public Policy Center. June 17, 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ Jillson, Cal. American Government: Political Change and Institutional Development. Psychology Press. ISBN 0415960770.

- ↑ US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-289. Report submitted March 27, 2014.

- 1 2 US Department of Labor, Office of Labor-Management Standards. File number 000-106. (Search)

- ↑ Constitution Art. X, Sec. 17

- ↑ Nelson Lichtenstein, State of the Union: A Century of American Labor (2nd ed. 2013)

- ↑ William Holley; et al. (2011). The Labor Relations Process. Cengage Learning. p. 153ff.

- ↑ AFL–CIO, "AFL–CIO Announces Huge 'FINAL FOUR' GOTV Push" "Press release" Oct. 30 2010

- ↑ Walsh, Deirdre (October 25, 2010). "AFL–CIO steps up get-out-the-vote effort". CNN. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Paul (13 November 2012). "Campaign Finance Reformers Get Back To Work". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Mahoney, Brian (June 13, 2016). "AFL-CIO to endorse Clinton Thursday". Politico. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ↑ Ray M. Tillman and Michael S. Cummings, The Transformation of U.S. Unions: Voices, Visions, and Strategies from the Grassroots (1999) pp 49-60 explains in detail the governance structure of the AFL–CIO

- ↑ See "Executive Council"

- ↑ Galvin, Kevin (19 February 1996). "AFL–CIO saying goodbye to fun in sun as it fights decline". Houston Chronicle. p. 5.

The Bal Harbour meeting dates to 1951, before the American Federation of Labor merged with the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

- ↑ Stieghorst, Tom (21 December 1991). "Afl–cio May Cancel Annual Trip Sheraton Bal Harbor Focus Of Labor Dispute". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ↑ Sturr, Chris (24 September 2009). "The Staley Lockout (Thad Williamson)". Dollars & Sense. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

In of the book’s most memorable scenes, Staley workers made a pilgrimage to AFL–CIO executive council meetings in Bal Harbour, Florida in February 1995, confronting stunned national leaders inside the luxurious Sheraton Hotel.

- ↑ Carmichael, Dan (19 February 1986). "Maverick strikers refused meeting". United Press International.

Renegade strikers at a Minnesota Hormel plant were refused entrance to an AFL–CIO Executive Council meeting Wednesday and they accused President Lane Kirkland and other labor leaders of being 'out of touch' with workers.

- ↑ "Media Advisory for AFL–CIO Executive Council Meeting February 17–20". Press Releases. AFL–CIO. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

Top leaders of the AFL–CIO will meet for nearly a week at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles beginning Sunday, February 16th – the first time in more than 30 years that the winter executive council meeting has not been held in the resort town of Bal Harbour, Florida.

- ↑ Hershey, William (23 February 1996). "Union Meeting Heads for L.A.: After 70 Years of Flocking to Florida, AFL–CIO Will Go Where There's Work, Organizing to Be Done". Akron Beacon Journal. p. B8.

- ↑ Strope, Leigh (9 March 2004). "AFL–CIO President Says Bush AWOL on Jobs". Associated Press Online.

The decision to return to Bal Harbor, where room rates for the meeting start at $225 a night, was made a few years ago to avoid losing deposit money, Sweeney said.

- ↑ Daraio, Robert (14 March 2012). "The AFL–CIO Executive Council and the IATSE General Executive Board Endorses Obama for Second Term". Broadcast Union News. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ↑ Michelle Amber, "SEIU Agrees to Pay Nearly $4 Million to Settle Dispute With AFL–CIO Over Dues," Daily Labor Report, March 2, 2006.

- ↑ Gilroy, Tom. "Labor to Stress Get-Out-the-Vote Among Members in Fall Elections," Labor Relations Week, October 21, 1998.

- ↑ Under AFL–CIO president Lane Kirkland, the Free Trade Union Committee had four units: the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD), which covered Latin America; the African-American Labor Center (AALC); the Asian-American Free Labor Institute (AAFLI); and the Free Trade Union Institute (FTUI), which was active Europe. These four units were merged into the American Center for International Labor Solidarity in 1997.

- ↑ Robert Anthony Waters and Geert van Goethem, eds., American Labor's Global Ambassadors: The International History of the AFL–CIO During the Cold War (Palgrave Macmillan; 2014)

- ↑ Targ, Harry (24 May 2010). "Class and Race in the US Labor Movement: The Case of the Packinghouse Workers". Political Affairs. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ↑ Sustar, Lee (28 June 2012). "Socialist Worker". Blacks and the Great Depression. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

But the well-entrenched bureaucrats of the AFL had long used racism to keep strict control over their membership, and could not countenance the threat of a racially united rank and file.

- ↑ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, p. 184, Random House, New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ↑ Hill, Herbert (Spring 1961). "Racism Within Organized Labor: A Report of Five Years of the AFL–CIO, 1955- 1960". The Journal of Negro Education. 30 (2): 109–118. doi:10.2307/2294330. JSTOR 2294330.

- ↑ Honey, Michael K. (2007). "Dr. King, Labor, and the Civil Rights Movement". Going down Jericho Road the Memphis strike, Martin Luther King's last campaign. New York [u.a.]: Norton. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

He optimistically projected a coalition in which registered blacks and organized labor would vote together to improve the conditions of all Americans. Yet King did not shirk from condemning union racism, nor did Randolph and the NAACP, leading to open conflict with AFL–CIO president George Meany.

- ↑ Honey, Michael K. (2007). "Standing at the Crossroads". Going down Jericho Road the Memphis strike, Martin Luther King's last campaign. New York [u.a.]: Norton. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-393-04339-6.

King's antiwar position opened a huge gap between him and the AFL–CIO, its member unions, and its president, George Meany, who strongly supported the war.

- ↑ Dubofsky, Melvyn (1994). The State & Labor in Modern America. University of North Carolina Press. p. 223. ISBN 9780807844366.

- ↑ Edsall, Thomas B. (July 26, 2005). "Two Top Unions Split From AFL–CIO, Others Are Expected To Follow Teamsters". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Steven. "Third Union Is Leaving A.F.L.-C.I.O." New York Times. July 30, 2005.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Steven. "4th Union Quits A.F.L.-C.I.O. in a Dispute Over Organizing." New York Times. September 15, 2005.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Steven. "Washington: United Farm Workers Quit A.F.L.-C.I.O." New York Times. January 13, 2006.

- ↑ "Laborers' Announce Official Split With AFL–CIO As of June 1." Engineering News-Record. May 29, 2006; "Laborer's to Make AFL–CIO Break Official." Chicago Sun Times. May 23, 2006.

- ↑ Larrubia, Evelyn. "UNITE HERE Faction Sets Vote on Leaving Union." Los Angeles Times. March 7, 2009; Mishak, Michael. "UNITE HERE Even More Split as Co-Leader Resigns in Huff." Las Vegas Sun. May 31, 2009; Greenhouse, Steven. "Infighting Distracts Unions at Crucial Time." New York Times. July 8, 2009.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Steve. "Union Rejoining A.F.L.-C.I.O." New York Times. September 17, 2009; Stutz, Howard. "Culinary Parent UNITE HERE Rejoins AFL–CIO, Ending Four-Year Separation." Las Vegas Review-Journal. September 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Construction Workers' Union to Rejoin A.F.L.-C.I.O." Associated Press. August 14, 2010.

- ↑ "Longshore Union Pulls Out of National AFL–CIO." Associated Press. August 31, 2013. Accessed 2013-08-31.

Further reading

- Amber, Michelle. "SEIU Agrees to Pay Nearly $4 Million to Settle Dispute With AFL–CIO Over Dues." Daily Labor Report. March 2, 2006.

- Arnesen, Eric, ed. Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History (2006), 3 vol; 2064pp; 650 articles by experts excerpt and text search

- Gilroy, Tom. "Labor to Stress Get-Out-the-Vote Among Members in Fall Elections." Labor Relations Week. October 21, 1998.

- Greenhouse, Steven. "For Chairwoman of Breakaway Labor Coalition, Deep Roots in the Movement." New York Times. October 10, 2005.

- Lichtenstein, Nelson. "Two Roads Forward for Labor: The AFL–CIO's New Agenda." Dissent 61.1 (2014): 54-58. Online

- Lichtenstein, Nelson. State of the Union: A Century of American Labor (2nd ed. 2013)

- Mort, Jo-Ann, ed. Not Your Father's Union Movement: Inside the AFL–CIO (2002)

- Rosenfeld, Jake. What Unions No Longer Do. (Harvard University Press, 2014) ISBN 0674725115

- Tillman, Ray M. and Michael S. Cummings. The Transformation of U.S. Unions: Voices, Visions, and Strategies from the Grassroots (1999)

- Yates, Michael D. Why Unions Matter (2009)

Constitution

- Constitution of the AFL–CIO, as amended at the Twenty-Fifth Constitutional Convention, July 25-28, 2005. Accessed January 15, 2007.

Further reading

Archives

- AFL–CIO Region 9 Records. circa 1955-2000. 14.00 cubic feet (14 boxes). At the Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

- Preliminary Guide to the AFL–CIO King County Labor Council of Washington Provisional Trades Section Records. 1935-1971. .42 cubic foot (1 box). At the Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

- AFL–CIO, Washington State Labor Council Records. 1919-2010. 187.18 cubic feet. At the Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

- Washington State Federation of Labor Records. 1901-1967. 45.44 cubic feet (including 2 microfilm reels, 1 package, and 1 vertical file). At the Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

- Antonia Bohan 1995 AFL–CIO Convention Delegate Collection. 1995-1996. 0.39 cubic feet (1 box and 1 oversized folder). At University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Contains material collected by Bohan as a Service Employees International Union delegate to the AFL–CIO convention that elected John Sweeney president in 1995.

- Jackie Boschok Papers. 1979-2011. 16.32 cubic feet (22 boxes). At University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Contains records from AFL–CIO National Community Services Documents, AFL–CIO Resources, and AFL–CIO Working Women Working Together Conference Records.

- Phil Lelli Papers. 1933-2004. 10.45 cubic feet (11 boxes and 1 vertical file). At University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Contains "Principles of Autonomy & Jurisdictional Intergrity within the AFL–CIO".

- George Meany Memorial AFL–CIO Archive. Approximately 40 million documents. At University of Maryland Libraries, Special Collections and University Archives. Contains material that will help researchers better understand pivotal social movements in this country, including those to gain rights for women, children and minorities.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to AFL-CIO. |

- AFL–CIO official website

- One Hat for Labor? by David Moberg, The Nation, April 29, 2009.

- Labor's Cold War by Tim Shorrock. The Nation, May 19, 2003.

- AFL–CIO on OpenSecrets.org