Abaco Islands

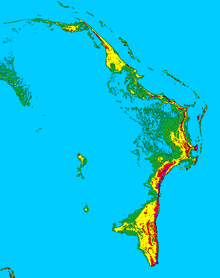

The five administrative districts of the Abacos. | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 26°28′N 77°05′W / 26.467°N 77.083°WCoordinates: 26°28′N 77°05′W / 26.467°N 77.083°W |

| Archipelago | Bahamas |

| Major islands | Great Abaco Island, Little Abaco Island |

| Area | 2,009 km2 (776 sq mi)[1] |

| Administration | |

| Island | Abaco |

| Largest settlement | Marsh Harbour (pop. 5,728) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 17,224 (2010) |

| Pop. density | 8.6 /km2 (22.3 /sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Blacks, Whites, Mixed |

The Abaco Islands lie in the northern Bahamas 180 miles (290 km) east of south Florida with similar weather with the exception of local patterns. They comprise the main islands of Great Abaco and Little Abaco, along with smaller barrier cays. The northernmost are Walker's Cay, and its sister island Grand Cay. To the south, the next inhabited islands are Spanish Cay and Green Turtle Cay, with its settlement of New Plymouth, Great Guana Cay, private Scotland Cay, Man-O-War Cay, and Elbow Cay, with its settlement of Hope Town. Southernmost are Tilloo Cay and Lubbers Quarters. Another of note off Abaco's western shore is onetime Gorda Cay, now a Disney Island and cruise ship stop and renamed Castaway Cay. Also in the vicinity is Moore's Island. On the Big Island of Abaco is Marsh Harbour, the Abacos' commercial hub and the Bahamas' third largest city, plus the resort area of Treasure Cay. Both have airports. A few mainland settlements of significance are Coopers Town and Fox Town in the north and Cherokee and Sandy Point in the south.[2] Administratively, the Abaco Islands constitute seven of the 31 Local Government Districts of the Bahamas: Grand Cay, North Abaco, Green Turtle Cay, Central Abaco, South Abaco, Moore's Island, and Hope Town.

Geography

Unlike the sandy barrier islands of the eastern US, here the islands consist of limestone with some elevation and are protected on the ocean side by the third largest barrier reef in the world. For the most part the cays are green with mangroves and white-sand beaches. Most are uninhabited. The Abacos and their cays have been called Out Islands, Family Islands and Friendly Islands.[2]

History

The Abaco Islands were first inhabited by the Lucayans. The first European settlers of the islands were Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution who arrived in 1783, as was also the case at Cat Island. These original Loyalist settlers made a modest living by salvaging wrecks, by building small wooden boats, and by basic farming.

Pre-Columbian and Spanish eras

The original inhabitants of the Bahamas before the arrival of Europeans were the Lucayans. They were a branch of the Taínos who inhabited most of the Caribbean islands at the time. The Lucayans were the first inhabitants of the Americas encountered by Christopher Columbus. The Spanish started seizing Lucayans as slaves within a few years of Columbus's arrival, and they had all been removed from the Bahamas by 1520. After the extermination of the Lucayans, there were no known permanent settlements in the Bahamas for approximately 130 years.[3]

Spain laid claim to the Bahamas after Columbus's discovery of the islands but showed little interest in them. The Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci spent four months exploring the Bahamas in 1499–1500. Juan de la Cosa's first map of the New World, printed in 1500, shows the Abaco Islands with the name Habacoa. The map in Peter Martyr's first edition of 'De Orbe Novo' in 1511 shows the islands of the Bahamas but does not name them. The Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León landed on Abaco in 1513. The Turin map of 1523 clearly shows Abaco, now named Iucayonique. This remained the most accurate map of the area until the first English maps of the Bahamas were produced. Both John White's map of 1590 and Thomas Hood's map of 1592 show the islands, as did a map produced in 1630 by the Dutchman de Laet.[3] At this time the Spanish empire in the Caribbean was focused on Havana. Spain regarded the, now depopulated, Bahamas as unprofitable and treacherous to navigate;- in 1593 a Spanish fleet of 17 ships was wrecked off Abaco. Also, English and French pirates and freebooters had begun preying on Spanish vessels north of Cuba. A Spanish ordinance of 1561 forbade any merchant ship to enter the Bahamas without an escort.[3] Ownership of the Bahamas passed back and forth between Spain and Great Britain for 150 years, until British ownership was established by treaty in 1783, when Great Britain ceded East Florida to Spain, receiving the Bahamas in return.

British colonial era

In the summer of 1783, about 1500 Loyalists left New York and moved to Abaco.[4] They planned and built the town of Carleton, probably present-day Hope Town.[3] Disputes over food distribution led some of these settlers to found a rival town at Marsh Harbour. Conflict between disgruntled settlers and the officials responsible for helping became a constant feature of life on the islands. Sea island cotton was first sown by the settlers in 1785 and although both 1786 and 1787 produced good crops, the 1788 crop was blighted by caterpillars.[4] Other settlements on the islands were Green Turtle Cay, Man-o-War Cay, and Sandy Point.[1] In the 1790s, a group of Loyalists from the Carolinas arrived on the islands via Florida, founding the isolated settlement of Cherokee Sound.[5]

1970s

In June 1971 the Prime Minister of the Bahamas, Lynden Pindling, announced his government's plans for independence from Britain. On Abaco, the Greater Abaco Council was formed to lobby for continued British rule. In July 1971 the Greater Abaco Council submitted a petition to the Queen asking that Abaco become a 'completely self-contained and fully self-supporting' territory under British jurisdiction.[6] In August 1971 the British Government refused to consider the petition. The September 1972 general election in the Bahamas showed a clear majority for independence across the country.

However, on Abaco the results were less clear cut. The pro-independence Progressive Liberal Party won one of Abaco's two seats by a small majority, while the Free National Movement, who opposed early independence, won the other seat by a large majority. Starting in December 1971, all party talks took place in London to draft a new constitution for the Bahamas. The Greater Abaco Council sent representatives to London for a 'collateral conference' to run alongside the official talks. The British refused to consider making Abaco independent separately from the rest of the Bahamas. The GAC accepted this and the group ceased activity at the end of 1972.[6]

Shortly afterwards, Errington Watkins, the Free National Movement representative for the Abaco-Marsh Harbour seat, formed a successor group, the Council for a Free Abaco. A second petition was organised and signed by half the registered voters on the island. Errington Watkins took this petition to London in May 1973, hoping to influence the Bahamas Independence Order then being debated in the British Parliament. A sympathetic MP, Ronald Bell introduced an amendment that would have excluded Abaco from an independent Bahamas and have the islands remain a British colony.[7] This amendment was defeated in the House of Commons and the Bahamas Independence Order[8] was approved on 22 May 1973. Three weeks later a similar motion on Abaco was defeated in the House of Lords.

A last-ditch attempt by Errington Watkins to pass a resolution in the Bahamas House of Assembly calling for a United Nations-supervised referendum on Abaco was easily defeated in June 1973[6] and the Bahamas became independent on 10 July 1973.

Abaco Independence Movement

In August 1973, shortly after the Bahamas became independent, the Abaco Independence Movement was formed as a political party whose stated aim was self-determination for Abaco within a federal Bahamas. AIM was formed by Chuck Hall and Bert Williams.[9] They sought support from the US Libertarian Party and an American financier named Michael Oliver, who through his libertarian Phoenix Foundation agreed to support AIM financially. Mitchell WerBell, an American arms dealer and mercenary, also supported AIM. His talk of an armed insurrection and attempts to recruit mercenaries to go to Abaco greatly discredited AIM.[10] The Progressive Liberal Party victory in the 1977 general election, effectively marked the end of the movement.[9]

Demographics

The combined population of the islands is about 17,224 as of 2010, and the principal settlement and capital is Marsh Harbour. The racial make up is about 50% white and 50% black.

In addition to Marsh Harbour there are several other settlements on Great Abaco including Cherokee Sound, Coopers Town, Crossing Rock, Green Turtle Cay, Hope Town, Little Harbour, Rocky Point, Sandy Point, Spring City, Treasure Cay, Wilson City, and Winding Bay.

Surrounding Great Abaco are several smaller islands known as cays, many of which are popular with tourists visiting the islands. A few notable cays include Castaway Cay (formerly Gorda Cay), Elbow Cay, Tilloo Cay, the Grand Cays, Great Guana Cay, Man-O-War Cay, Green Turtle Cay, Moore's Island, and Walker's Cay.[11]

Activities

The Bahamas National Trust maintains six national parks in the Abacos Islands.[12] These are:

- Pelican Cays Land & Sea Park

- Abaco National Park

- Black Sound Cay National Reserve

- Walker's Cay National Park

- Tilloo Cay National Reserve

- Fowl Cays National Reserve

The Great Abaco Family Fitness weekend takes place every March in Treasure Cay, attracting both domestic and international tourism. The events include an open water swim, sprint and Olympic triathlons, a children's race, and a 5k/10k fun run/walk.

Transportation

Marsh Harbour Airport (MHH) and Treasure Cay Airport (TCB) serve the needs of the Abacos, and all Abaco travel connects or originates in Florida or Atlanta. On the main island cars and boat rentals are available. On some of the cays, rental golf carts and boats are the main mode of transportation, along with bikes or scooters. Marsh Harbour Airport was the site of a plane crash that took the lives of nine people, among them was R&B singer Aaliyah, on August 25, 2001.[13]

The cays can be reached by ferries. The southern cays can be reached from Marsh Harbour and another ferry leaves from the Treasure Cay ferry dock about a half-hour from Marsh Harbour by road. Ferry service is also to be found between Nassau and Sandy Point on the southern end of Great Abaco on weekends.

Economy

The Abaco Islands have been long famous for shipbuilding.[14] Their chief exports are lumber, fruit, and pearl shells. Crawfish (Caribbean spiny lobster) are exported to the United States. Pulpwood is shipped to a Florida plant for processing. Tourism is a major portion of the economy.[1]

Environment

The Abaco Islands boast important natural areas, especially important coral reef areas, barrier-island terrestrial habitats and large forests of Bahamian pine (Pinus caribaea var. bahamensis), some of which still contain old-growth trees. As development expands in the Abacos, local groups have begun to fight for the preservation of their natural resources, such as in the development case on Great Guana Cay.[15]

Notable species of birds include the Bahamian subspecies of Cuban amazon (Amazona leucocephala bahamensis), which exists only in Cuba, the Cayman Islands, the southern Bahamas and Abaco.[16] This population is unique in that it nests in limestone solution cavities rather than tree cavities.[17] Abaco is also known for its intact elkhorn and staghorn coral structures, and for its critically endangered breed of feral horse, the Abaco Barb.

References

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Abacos. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abaco Islands. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article Abaco. |

- 1 2 3 Bower, Paul (1997). "Abaco Islands". In Johnston, Bernard. Collier's Encyclopedia. I A to Ameland (First ed.). New York, NY: P.F. Collier. p. 4.

- 1 2 Estabrook, Sandy. "Welcome to the Abacos". abacoescape.com. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Craton, Michael (1969) [First published 1962]. A History of the Bahamas. Collins. OL 2653684W.

- 1 2 Maya Jasanoff (2011). Liberty's Exiles, The Loss of America and the Remaking of the British Empire. Harper Press. ISBN 978-0-00-718010-3.

- ↑ "Abaco Island, The Bahamas". North Carolina Language and Life Project. North Carolina State University. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Rick Lowe (July 2010). "Forgotten Dreams: A People's desire to chart their own course in Abaco, Bahamas Part One" (PDF). The Nassau Institute. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ "Bahamas Independence Bill". Hansard. May 1973. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ↑ "The Bahamas Independence Order, 1973" (PDF). bahamas.gov.bs. Government of the Bahamas. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- 1 2 Rick Lowe (October 2010). "Forgotten Dreams: A People's desire to chart their own course in Abaco, Bahamas Part Two" (PDF). The Nassau Institute. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ↑ St. George, Andrew (February 1975). "The Amazing New-Country Caper". Esquire.

- ↑ Diving in Abaco Bahamas, Retrieved 6 November 2013

- ↑ Bahamas National Trust (2012). "The National Parks of The Bahamas". BNT. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ NTSB Identification: MIA01RA225 (Report). National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ↑ "Man-O-War's Boat Building Heritage". Man-O-War Cay Museum. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ Teresa Castle; Chronicle Foreign Service (13 February 2006). "Reef defenders in Bahamas sue over mega-resort / S.F. developer sees Baker's Bay as model for sensitive construction on fragile islands". Sfgate.com. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ↑ "Rose-throated Parrot (Amazona leucocephala)". Society for the Conservation and Study of Caribbean Birds (SCSCB). December 2006.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Amazona leucocephala". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 16 July 2012.