Acoustic torpedo

An acoustic torpedo is a torpedo that aims itself by listening for characteristic sounds of its target or by searching for it using sonar (acoustic homing). Acoustic torpedoes are usually designed for medium-range use, and often fired from a submarine.

The first passive acoustic torpedoes were developed independently and nearly simultaneously by the Allies and the Germans during World War II. The Germans developed the G7e/T4 Falke, which was first deployed in March 1943. However, this early model was actually used in combat by only three German U-Boats. It was not until after the deployment of the T-4's successor, the G7es T-5 Zaunkönig torpedo in August 1943 that Germany began to use passive acoustic torpedoes in substantial numbers; the T-5 first saw widespread use in September 1943. This weapon was developed to attack escort vessels and merchant ships in convoys.

The initial impact of the acoustic torpedo in the Battle of the Atlantic prior to the widespread deployment of counter-measures cannot be overstated. The U-boats now had an effective "fire and forget" weapon capable of homing-in on attacking escorts and merchant ships and doing so in close quarters of only three or four hundred yards.[1] By Summer of 1943, the German U-boat campaign was experiencing severe setbacks in the face of massive anti-submarine efforts integrating Coastal Command attacks in the Bay of Biscay, the deployment of merchant aircraft carriers in convoys, new anti-submarine technologies such as hedgehog and improved radar, and the use of dedicated hunter-killer escort groups. The Allies' improved escorts had greater range, and the use of fuelling at sea added hundreds of miles to the escort groups' radius of action. From June through August, 1943 the number of merchant ships sunk in the Atlantic was almost insignificant, while the number of U-boat kills rose dramatically and caused a general withdrawal from battle as the submarines could hardly make it through the Bay of Biscay to engage the convoys. For a time, the acoustic torpedo again put the escorts and convoys on the defensive, starting with the attacks in September, 1943 on Convoys ONS-18/ON-202.[2]

In September 1944, Russian commando frogmen discovered T-5 torpedoes aboard the German submarine U-250, which had been sunk in shallow waters by the depth charges of the Soviet submarine chasers Mo 103 and Mo 105 off Beryozovye Islands. Torpedoes were safely delivered to surface ships.[3] Key components of the G7es T-5 Zaunkönig torpedo were later ordered by Joseph Stalin to be given to British naval specialists. However, after a protracted journey to Kronstadt the two Royal Navy officers were not allowed access to the submarine and returned home empty handed.[4] The capture of U-505 marked the second time that allied forces gained access to this technology. The T-5 was countered by the introduction by the Allies of the Foxer[5] noise maker.

On the Allied side, the US Navy developed the Mark 24 mine. The Mark 24 was called a mine for security reasons; it was actually an aircraft launched, anti-submarine passive acoustic homing torpedo. The first production Mk. 24s were delivered to the U.S. Navy in March 1943, and it scored its first verified combat kills in May 1943. The Mk. 24 went on to become a successful anti-submarine weapon and later in the war was also adapted for submarine and surface ship use.

Since its introduction, the acoustic torpedo has proven to be an effective weapon against surface ships as well as serving as an anti-submarine weapon. Today, acoustic torpedoes are mostly used against submarines.

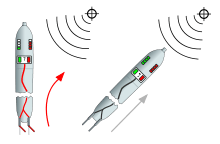

Before a torpedo is launched, the target must be 'boxed in'. A fire control system on the firing platform will set an initial search depth range which is passed to the weapon's microprocessor. The search parameters cover the expected depth of the target.

Acoustic homing torpedoes are equipped with a pattern of acoustic transducers on the nose of the weapon. By a process of phase delaying the signals from these transducers a series of "acoustic beams" (i.e. a variation of acoustic signal sensitivity dependent on the incident angle of the noise energy). In early homing torpedoes the "beam patterns" were fixed whereas in more modern weapons the patterns were modifiable under on-board computer control. These sensor systems are capable of either detecting sound originating from the target itself i.e. engine and machinery noise, propellor cavitation, etc., known as passive sonar, or responding to noise energy reflections as a result of "illuminating" the target with sonar pulses, known as active sonar. Acoustic torpedoes can be compared to modern fire-and-forget guided missiles. What this means is the enemy (most likely a submarine) will be detected by sonar in any direction it goes. The torpedo will start with passive sonar, simply trying to detect the submarine. Once the torpedo's passive sonar has detected something, it will switch over to an active sonar and will begin to track the target. At this point, the submarine has probably started evasive maneuvers and may have even deployed a noisemaker. The torpedo's logic circuitry, if not fooled by the noise maker, will home in on the noise signature of the target submarine.

Military examples

- United States

- RUR-5 ASROC - Ship-launched anti-submarine missile

- MK 48 - ADCAP submersion launch torpedo

- MK 24 / MK 27 - Passive homing surface / submersible fire torpedo

- MK 32 - Active homing surface / submersible / air fire torpedo

References

- Notes

- ↑ Schull, Joseph (1961). The Far Distant Ships (Canadian Ministry of National Defence ed.). Ottawa: Queen's Printer, Ottawa Canada. pp. 180, 181.

- ↑ Schull, Joseph (1961). The Far Distant Ships (Canadian Ministry of National Defence ed.). Ottawa, Canada: Queen's Printer, Ottawa Canada. pp. 176–183.

- ↑ The Type VIIIC boat U-250, List of All U-boats, uboat.net

- ↑ Lincoln, Ashe (1961) Secret Naval Investigator London: William Kimber and Co. Ltd, page 176.

- ↑ Lincoln, Ashe (1961) Secret Naval Investigator London: William Kimber and Co. Ltd, pages 172 to 176.

- Bibliography

- Cutler, Thomas J. The Battle of Leyte Gulf. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996

- Clancy, Tom. Red Storm Rising. New York: Penguin and Putnam, 1986