Adam von Trott zu Solz

| Adam von Trott zu Solz | |

|---|---|

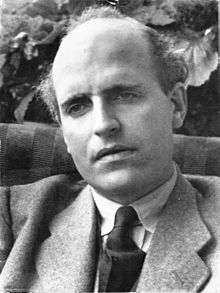

Trott zu Solz in 1943 | |

| Born |

9 August 1909 Potsdam, Germany |

| Died |

26 August 1944 (aged 35) Plötzensee Prison, Berlin |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Diplomat, lawyer |

| Known for | Opposing the Nazi government and taking part in the July 20th Plot |

| Spouse(s) | Clarita Tiefenbacher (1940-1944 his death) |

| Parent(s) |

|

Friedrich Adam von Trott zu Solz (9 August 1909 – 26 August 1944) was a German lawyer and diplomat who was involved in the conservative resistance to Nazism. A declared opponent of the Nazi regime from the beginning, he actively participated in the Kreisau Circle of Helmuth James Graf von Moltke and Peter Yorck von Wartenburg. Together with Claus von Stauffenberg he conspired in the 20 July plot, supposed to be appointed Secretary of State in the Foreign Office and lead negotiator with the western allies if they had succeeded.

Life

Adam von Trott was born in Potsdam, Brandenburg, into the Protestant Trott zu Solz dynasty, members of the Hessian Uradel nobility. He was the fifth child of the Prussian Culture Minister August von Trott zu Solz (1855–1938) and Emilie Eleonore (1875–1948), née von Schweinitz, whose father served as German ambassador in Vienna and Saint Petersburg. By her mother Anna Jay, Emilie Eleonore was a great-great granddaughter of John Jay, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and the first Chief Justice.

Adam von Trott zu Solz was first raised in Berlin and from 1915 was sent to the Französisches Gymnasium preschool. When his father resigned from office in 1917, the family moved to Kassel where von Trott attended the Friedrichsgymnasium. From 1922 he lived in Hann. Münden and temporarily joined the German Youth Movement. He obtained his Abitur degree in 1927 and went on to study law at the universities of Munich and Göttingen.

Von Trott developed a strong interest in international politics during a stay in Geneva, seat of the League of Nations, for several weeks in Autumn 1928. He spent hilary term of 1929 in Oxford studying theology at Mansfield College, Oxford, and returned to the UK in 1931 on a Rhodes Scholarship to study at Balliol College, Oxford where he became a close friend of David Astor and an acquaintance of the eminent philosopher R. G. Collingwood.[1] Following his studies at Oxford, he spent six months in the United States.

Travels

In 1937, Trott was posted to China. He took advantage of his travels to try to raise support outside Germany for the internal resistance against the Nazis. In 1939, he lobbied Lord Lothian and Lord Halifax to pressure the British government to abandon its policy of appeasement towards Adolf Hitler, visiting London three times. He also visited Washington, D.C. in October of that year in an unsuccessful attempt to obtain American support. He met with Roger Baldwin, Edward C. Carter, William J. Donovan, and Felix Morley of the Washington Post.[2]

Foreign office

Friends warned Trott not to return to Germany but his conviction that he had to do something to stop the madness of Hitler and his henchmen led him to return. Once there, in 1940 Trott joined the Nazi Party in order to access party information and monitor its planning. At the same time, he served as a foreign policy advisor to the clandestine group of intellectuals planning the overthrow of the Nazi regime known as the Kreisau Circle.

In late spring 1941, Wilhelm Keppler, under-Secretary of State at the German Foreign Office, was appointed director of Special Bureau for India (Sonderreferat Indien)[3][4] created in the Information Ministry to aid,[3] and liaise with,[4] Indian nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose, former president of the Indian National Congress, who had arrived in Berlin in early April 1941.[5] The day-to-day work with Bose became the responsibility of Trott.[4] Trott used the cover of the Special Bureau for his anti-Nazi activities,[6][4] traveling to Scandinavia, Switzerland, and Turkey, and in addition, all of Nazi-occupied Europe to seek out German military officers opposing Nazism.[7] Bose and Trott, however, did not become close,[8] and Bose most likely did not know about Trott's anti-Nazi work.[7] According to historian Leonard A. Gordon, there were also tensions between Trott and Bose's wife, Emilie Schenkl, each disliking the other intensely.[7]

20 July 1944 plot

Trott was one of the leaders of Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg's plot of 20 July 1944 to assassinate Hitler. He was arrested within days, placed on trial and found guilty. Sentenced to death on 15 August 1944 by the Volksgerichtshof (People's Court), he was hanged in Berlin's Plötzensee Prison on 26 August.

Balliol tributes

Trott is one of five Germans who are commemorated on the World War II memorial stone at Balliol College, Oxford. His name is also recorded among the Rhodes Scholars war dead in the Rotunda of Rhodes House, Oxford.[9]

In July 1998, the British magazine Prospect published an edited version of the lecture given by the German historian Joachim Fest at the inauguration of the Adam von Trott Meeting Room at Balliol College, Oxford. Fest said:

Few witnesses have spoken up for the resistance and few sentences have survived to describe the debates of the "Kreisauer Kreis," the urgent pleas of Stauffenberg and Tresckow, the thoughts of Haefte, Moltke, York and Leber. Trott's final memorandum - he said he had put his heart into it - has also been lost. Even the minutes of the hearings in the People's Court, where the conspirators were able to proclaim the principles which had governed their actions for the last time, have only survived as fragments: some were manipulated by the censor.This silence from the original sources has prolonged the isolation which surrounded the resistance from its beginnings. In fact, it has contributed to what might be called its second defeat. Commemorating the name of Adam von Trott in a meeting room at Balliol College is thus an act of justice.[10]

Clarita von Trott

Adam von Trott married Clarita Tiefenbacher in June 1940. He was survived by his wife, who was jailed for some months, and by their two daughters, who were taken from their grandmother's house by the Gestapo and given to Nazi Party families for adoption. Their mother recovered them in 1945. Clarita von Trott died in Berlin, at the age of 95, on 28 March 2013.[11]

Quotes

- "I am also a Christian, as are those who are with me. We have prayed before the crucifix and have agreed that since we are Christians, we cannot violate the allegiance we owe God. We must therefore break our word given to him who has broken so many agreements and still is doing it. If only you knew what I know Goldmann! There is no other way! Since we are Germans and Christians we must act, and if not soon, then it will be too late. Think it over till tonight."[12] (Adam von Trott zu Solz speaking in an attempt to recruit Lieutenant Gereon Goldmann, a Wehrmacht medic and former Roman Catholic seminarian. Lt. Goldmann had balked at violating the soldier's oath and had questioned the morality of assassinating Adolf Hitler. However, Goldmann overcame his qualms and joined the 20 July Plot as a carrier of dispatches).

Works

Adam von Trott was the author of:

- Hegels Staatsphilosophie und das internationale Recht; Diss. Göttingen (V&R), 1932

Notes

- ↑ For the impact on von Trott of his experience as a Rhodes Scholar, see, e.g., Donald Markwell, Instincts to Lead, 2013, pages 148-62 & passim

- ↑ von Klemperer, Klemens. (1992). German Resistance against Hitler: the Search for Allies Abroad, 1938-1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 148n. ISBN 0198219407.

- 1 2 Klemperer 1994, p. 275.

- 1 2 3 4 Gordon 1990, p. 445.

- ↑ Kuhlmann 2003, p. 158.

- ↑ Klemperer 1994, pp. 275–276.

- 1 2 3 Gordon 1990, p. 446.

- ↑ Hayes 2011, p. 211.

- ↑ John Jones (1999). "Memorial inscriptions". Balliol College Archives & Manuscripts. Balliol College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ↑ Joachim Fest: Portrait - Adam von Trott (Prospect magazine, London, July 1998, pp 48-53).

- ↑ Death of Clarita von Trott, osthessen-news.de; accessed 15 May 2015.(German)

- ↑ Fr. Gereon Goldmann, OFM, "The Shadow of his Wings," Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 2001. Page 86.

Cited references

- Gordon, Leonard A. (1990), Brothers against the Raj: a biography of Indian nationalists Sarat and Subhas Chandra Bose, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-07442-1

- Hayes, Romain (2011), Subhas Chandra Bose in Nazi Germany: Politics, Intelligence and Propaganda 1941-1943, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-932739-3

- Klemperer, Klemens von (1994), German Resistance Against Hitler: The Search for Allies Abroad 1938-1945, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-151334-3

- Kuhlmann, Jan (2003), Subhas Chandra Bose und die Indienpolitik der Achsenmächte, Berlin; Tübingen: Verlag Hans Schiler, ISBN 978-3-89930-064-2

- MacDonogh, Giles (1994), A good German: Adam von Trott zu Solz, Quartet Books, ISBN 978-0-7043-0215-0

- Sykes, Christopher (1968), Troubled loyalty: a biography of Adam von Trott zu Solz, London: Collins

Further reading

- Hedley Bull, Edited by: The Challenge of the Third Reich –The Adam von Trott Memorial Lectures Oxford University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-19-821962-8

- Christabel Bielenberg: The Past is Myself, Corgi, 1968. ISBN 0-552-99065-5. Published in the US as When I was a German, 1934-1945, University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8032-6151-9

- Shiela Grant Duff: Fünf Jahre bis zum Krieg (1934–1939), Verlag C.H.Beck, trans. Ekkehard Klausa, ISBN 3-406-01412-7. (In German)

- Shiela Grant Duff: The Parting of Ways—A Personal Account of the Thirties, Peter Owen, 1982, ISBN 0-7206-0586-5.

- The Earl of Halifax: Fulness of Days, Collins, 1957, London.

- Michael Ignatieff: A Life of Isaiah Berlin, Chatto&Windus, 1998, ISBN 0-7011-6325-9.

- Diana Hopkinson: The Incense Tree, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1968, ISBN 0-7100-6236-2.

- Annedore Leber, collected by: Conscience in Revolt—Sixty-four Stories of Resistance in Germany 1933-45, Valentine, Mitchell & Co, London 1957 (Das Gewissen Steht Auf, Mosaik-Verlag, Berlin, 1954).

- Klemens von Klemperer (Editor): A Noble Combat—The Letters of Shiela Grant Duff and Adam von Trott zu Solz, 1932-1939, 1988, ISBN 0-19-822908-9.

- Donald Markwell, "The German Rhodes Scholarships: an early peace movement", in Markwell, "Instincts to Lead": On Leadership, Peace, and Education, 2013, ISBN 9781922168702.

- A. L. Rowse: All Souls And Appeasement—A Contribution to Contemporary history, Macmillan & Co., London/New York, 1961.

- A. L. Rowse: A Man of The Thirties, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1979, ISBN 0-297-77666-5.

- A. L. Rowse: A Cornishman Abroad, Jonathan Cape, 1976, ISBN 0-224-01244-4.

- Clarita von Trott zu Solz: Adam von Trott zu Solz. Eine Lebensbeschreibung. Lukas Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86732-063-4. (In German)

- Marie Vassiltchikov (aka Maria Vasilchilkova): Berlin Diaries 1940-1945, 1988. ISBN 0-394-75777-7 (Vassiltchikov was a friend of Trott and other members of the 1944 plot)

- John W. Wheeler-Bennett: The Nemesis of Power—The German Army in Politics, 1918-1945 Macmillan & Co, London/New York, 1953.

- Sir John Wheeler-Bennett: Friends, Enemies and Sovereigns—The Final Volume of his Auto-biography, MacMillan, London 1976, ISBN 0-312-30555-9.

External links

- Adam von Trott zu Solz, jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- Adam von Trott zu Solz, wiesenthal.org

- Adam von Trott collection, Balliol College Archives & Manuscripts, University of Oxford