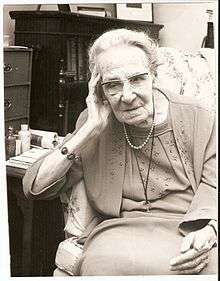

Alice Seeley Harris

| Lady Alice Seeley Harris | |

|---|---|

Alice Seeley Harris | |

| Born |

Alice Seeley 24 May 1870 Malmesbury, Wiltshire, England |

| Died |

24 November 1970 (aged 100) Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Occupation | Missionary, photographer, activist |

| Spouse(s) | John Hobbis Harris |

| Children | Alfred, Margaret, Katharine, Noel |

| Parent(s) | Alfred and Caroline Seeley |

Alice Seeley Harris (1870–1970)[1][2] was an English missionary and an early documentary photographer. Her photography helped to expose the human rights abuses in the Congo Free State under the regime of Leopold II, King of the Belgians.

Family and origins

Alice Seeley was born in Malmesbury, Wiltshire, England to Aldred and Caroline Seeley. Her sister, Caroline Alfreda, was a school teacher who never married. Alice married John Hobbis Harris (later Sir John) at a Registry Office in London. They had four children: Alfred John, Margaret Theodora, Katherine Emmerline (known as “Bay”) and Noel Lawrence. Alice spent many years in Frome, Somerset and died at the age of 100 in 1970 at Lockner Holt, in Surrey.

Career

In 1889, aged 19 yrs, Alice entered the Civil Service and was later appointed to the Accountant General’s office in GPO London. Alice gave her spare time to Frederick Brotherton Meyer’s mission work at Regent’s Park Chapel and later Christ Church, in Lambeth.

Alice left the Civil Service to enter Doric Lodge, the RBMU’s (Region Beyond Missionary Union, previously the Congo Balolo Mission) Missionary Training College and in 1894, met her future husband John Hobbis Harris. Finally in 1897, after seven years of trying, Alice was accepted to go out to the Congo Free State. Shortly afterwards, Alice and John got engaged and were married on 6 May 1898.

On the 10 May 1898, Alice and John departed on the SS Cameroon to the Congo Free State as missionaries with the Congo Balolo Mission, it was to be her ‘honeymoon’. They arrived in the Congo three months later, on the 4 August 1898, and then travelled to the Mission Station Ikau near Basankusu.

Alice was appalled and saddened at what she witnessed in the so-called Congo Free State, and began campaigning for the human rights of the Congolese natives to be recognised.[3]

Campaigner

Alice was stationed with her husband John from 1898 – 1901 at the Mission Station at Ikau. Ikau is located near the River Lulanga, which is a tributary of the River Congo in the Balolo Tribal region. Later, from 1901 - 1905, they were stationed at the Mission Station at Baringa, a village in Tshuapa District, Befale Territory in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It stands on the banks of the Maringa River, approximately 100km upriver from Basankusu.

During her time in the Congo, Alice taught English to the local children, but her most important contribution was to photograph the injuries that were sustained by the Congolese natives at the hands of the agents and soldiers of King Leopold II of Belgium.Leopold was partly exploiting the local population so fiercely to profit from increased rubber demand after the invention of the pneumatic or inflatable tire by John Boyd Dunlop in Belfast in 1887. Methods of coercion included whipping, hostage-taking, rape and murder, and burning of gardens and villages.

The most famous and shocking atrocity, whose aftermath Harris captured in her photography was the severing of hands. In 1904 two men arrived at their mission from a village attacked by 'sentries' of the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company (ABIR) after failing to provide the required rubber quota. One of the men, Nsala, was holding a small bundle of leaves which when opened revealed the severed hand and foot of a child. Sentries had killed and mutilated Nsala's wife and daughter. Appalled, Alice persuaded Nsala to pose with his child's remains on the veranda of her home for a picture.

Initially Alice's photographs were used in Regions Beyond, the magazine of the Congo Balolo Mission. In 1902, the pair returned to Britain temporarily. In 1904 Alice's photographs reached wider distribution including inside a pamphlet titled Congo Slavery that was prepared by Mrs. H. Grattan-Guinness, wife of the editor of Regions Beyond and in King Leopold's rule in Africa[4] by E. D. Morel. The same year saw the founding of the Congo Reform Association by Morel.

In early 1906, Alice and her husband toured the United States. John wrote that they had presented her images at 200 meetings in 49 cities via magic lantern screenings.

In 1906 Alice and her husband began working for Morel's Congo Reform Association.

In December 1906 the daily paper New York American used Harris's photographs to illustrate articles on atrocities in the Congo for an entire week.

In 1908, Alice and John became joint organizing secretaries of the Congo Reform Association and, in April 1910, they became joint organizing secretaries of the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines' Protection Society. Alice soon relinquished her official position, but assisted John at the Society until his death in 1940. She continued her very active speaking career and was listed with Christy's Lecture Service alongside luminaries such as Winston Churchill and Ernest Shackleton.

In November 1908 Leopold ceded administration of the Congo Free State to the Belgian government, thus creating the Belgian Congo.

The pair returned to the Congo from 1911–12, following the 1908 handover of the Congo to Belgium by King Leopold II. They noted improved conditions in the treatment of natives and later produced a book, Present Conditions in the Congo, illustrated with Alice's photographs. Soon thereafter, hundreds of Alice's African documentary photographs were displayed at an exhibition at the Colonial Institution.

In 1933, Alice's husband John was knighted for his services to humanity and Alice became Lady Alice, but is known for saying "...don't call me Lady!"[5] Some commentators think that Alice should have received an honour for her services, in her own right, in being one of the first people to use photography in a human rights campaign.

In 1970, Alice reached 100 years old and was interviewed by BBC Radio 4 on a programme "Women of Our Time"[6]

Legacy

From 16 January to 7 March 2014, Autograph ABP in Rivington Place, London held an exhibition titled When Harmony Went to Hell - Congo Dialogues: Alice Seeley Harris and Sammy Baloji[7]

From 24 January to 7 September 2014, the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool held an exhibition titled Brutal Exposure: the Congo centered on Alice's photographs.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Thompson, T. Jack (October 2002). "Light on the Dark Continent: The Photography of Alice Seely Harris and the Congo Atrocities of the Early Twentieth Century". International Bulletin of Missionary Research. 26 (4): 146–9.

- ↑ "Congo Dialogues: Alice Seeley Harris and Sammy Baloji", Autograph ABP. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ "Alice Seeley Harris".

She would have been only 27 when she went out there, I believe she was also pregnant

- ↑ "King Leopold's rule in Africa".

- ↑ Pollard Smith, Judy (20 Jan 2014). Don't Call Me Lady - The journey of Lady Alice Seeley Harris (First ed.). AbbottPress. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-45821-289-4.

- ↑ "Women of Our Time". Soundcloud. BBC Radio 4.

- ↑ "When Harmony went to Hell". Autograph ABP.

- ↑ "Brutal Exposure: the Congo".

Further reading

- Pavlakis, Dean (2015). British Humanitarianism and the Congo Reform Movement,1896-1913. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4724-3647-4.

- Sliwinski, Sharon (2006). "The Childhood of Human Rights: The Kodak on the Congo". Journal of Visual Culture. 5 (3): 333–63. doi:10.1177/1470412906070514.

- Peffer, John (2008). "Snap of the Whip/Crossroads of Shame: Flogging, Photography, and the Representation of Atrocity in the Congo Reform Campaign". Visual Anthropology Review. 24: 55–77. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7458.2008.00005.x.

- Hunt, Nancy Rose (2008). "An Acoustic Register, Tenacious Images, and Congolese Scenes of Rape and Repetition". Cultural Anthropology. 23 (2): 220–53. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2008.00008.x.

- Wylie, Lesley (2012). "Travel Writing and Atrocities: Eyewitness Accounts of Colonialism in the Congo, Angola, and the Putumayo". Nineteenth-Century Contexts. 34 (2): 192–4. doi:10.1080/08905495.2012.671686.

- "Women of Action". A Celebration of Women.