Ambroise Paré

| Ambroise Paré | |

|---|---|

Posthumous, fantasy portrait | |

| Born |

1510 Bourg-Hersent near Laval, France |

| Died |

20 December 1590 (aged 80) Paris, France |

| Citizenship | France |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | Barber Surgery |

Ambroise Paré (c. 1510 – 20 December 1590) was a French barber surgeon who served in that role for kings Henry II, Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. He is considered one of the fathers of surgery and modern forensic pathology and a pioneer in surgical techniques and battlefield medicine, especially in the treatment of wounds. He was also an anatomist and invented several surgical instruments. He was also part of the Parisian Barber Surgeon guild.

In his personal notes about the care he delivered to Captain Rat, in the Piémont campaign (1537–1538), Paré wrote: " Je le pansai, Dieu le guérit " (I bandaged him and God healed him). This epitomises a philosophy that he used throughout his career. [1][2] At this time, little could be done for battlefield wounds and injured soldiers were often put out of their misery by comrades if the wound was too severe to be treated. During the 1536 Battle of Milan, Paré encountered two men who had been horribly burned by gunpowder. A soldier came up and asked if anything could be done to help them, to which he shook his head. The soldier then calmly took out his dagger and proceeded to cut their throats. A horrified Paré shouted that he was "a villain", to which he was told "Were I in such a situation, I would only pray to God for someone to do the same for me."

Early career

Paré was born in 1510 in Bourg-Hersent in north-western France. As a child he watched, and was first apprenticed to, his older brother, a barber-surgeon in Paris. He was also a pupil at Hôtel-Dieu, France's oldest hospital. Paré first experienced being a battle medic at Piedmont, during the campaign of Francis I. When, one day, he was presented with more gunshot wounds than he had oil for, he improvised and used an old Roman technique, using oil of roses, egg white, and turpentine. He worried through the night that the soldiers would die, but to his surprise, he found the next morning that the soldiers treated with oil were in agony, their wounds swollen and some had even died during the night, whereas the men treated the Roman way were well rested, their wounds calm and beginning to heal. He then continued with this approach to sealing wounds, rather than the largely accepted method of cauterizing wounds. His new technique was not perfect, as there was still a chance of infection and the pain was still a problem, but both of these were a much smaller problem than when using boiling oil.

Medicine

Paré was a keen observer and did not allow the beliefs of the day to supersede the evidence at hand. In his autobiographical book, Journeys in Diverse Places, Paré inadvertently practiced the scientific method when he returned the following morning to a battlefield. He compared one group of patients who paid for treatment treated in the traditional manner with boiling elderberry oil and cauterization, and the remainder from a recipe made of egg yolk, oil of roses and turpentine, and left overnight. Paré discovered that the soldiers treated with the boiling oil were in agony, whereas the ones treated with the ointment had recovered because of the antiseptic properties of turpentine. This proved this method's efficacy, and he avoided cauterization thereafter.[3] However, treatments such as this were not widely used until many years later. He published his first book The method of curing wounds caused by arquebus and firearms in 1545.

Paré also reintroduced the ligature of arteries (first used by Galen) instead of cauterization during amputation.[4] The usual method of sealing wounds by searing with a red-hot iron often failed to arrest the bleeding and caused patients to die of shock. For the ligature technique he designed the "Bec de Corbeau" ("crow's beak"), a predecessor to modern haemostats. Although ligatures often spread infection, it was still an important breakthrough in surgical practice. Paré detailed the technique of using ligatures to prevent hemorrhaging during amputation in his 1564 book Treatise on Surgery. During his work with injured soldiers, Paré documented the pain experienced by amputees which they perceive as sensation in the 'phantom' amputated limb. Paré believed that phantom pains occur in the brain (the consensus of the medical community today) and not in remnants of the limb.[5]

In 1542, during the siege of Perpignan, Paré, accompanying the French army, employed a novel technique to aid in bullet extraction. During a battle, Maréchal de Brissac was wounded, having been shot in the shoulder. When finding the bullet seemed impossible, Paré had the idea to ask the victim to put himself in the exact position he was in when shot. The bullet was then found and removed by Henry's personal surgeon, Nicole Lavernault.[7]

Paré was also an important figure in the progress of obstetrics in the middle of the 16th century. He revived the practice of podalic version, and showed how even in cases of head presentation, surgeons with this operation could often deliver the infant safely, instead of having to dismember the infant and extract the infant piece by piece.

Paré also introduced the lancing of infants' gums using a lancet during teething, in the belief that teeth were failing to emerge from the gums due to lack of a pathway, and that this failure was a cause of death. This belief and practice persisted for centuries, with some exceptions, until towards the end of the nineteenth century lancing became increasingly controversial and was then abandoned.[8]

Paré was ably seconded by his pupil Jacques Guillemeau, who translated his work into Latin, and at a later period himself wrote a treatise on midwifery. An English translation of it was published in 1612 with the title Childbirth; or, The Happy Delivery of Women.

In 1552, Paré was accepted into royal service of the Valois Dynasty under Henry II; he was however unable to cure the king's fatal blow to the head, which he received during a tournament in 1559. Paré stayed in the service of the Kings of France to the end of his life in 1590, serving Henry II, Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III.

According to Henri IV's Prime Minister, Sully, Paré was a Huguenot and on 24 August 1572, the day of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, Paré's life was saved when King Charles IX locked him in a clothes closet. He died in Paris in 1590 from natural causes in his 80th year. While there is evidence that Paré may have been sympathetic to the Huguenot cause, he seems to have kept appearances of being Catholic to avoid danger: he was twice married, was buried, and had his children baptized into the Catholic faith.

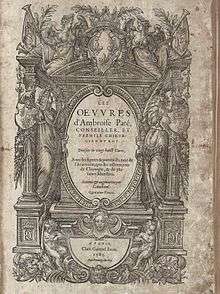

A collection of Paré's works (he published these separately throughout his life, based on his experiences treating soldiers on the battlefield) was published at Paris in 1575. They were frequently reprinted, several editions appeared in German and Dutch, and among the English translations was that of Thomas Johnson (1634).

Bezoar stone experiment

In 1567, Ambroise Paré described an experiment to test the properties of bezoar stones. At the time, the stones were commonly believed to be able to cure the effects of any poison, but Paré believed this to be impossible. It happened that a cook at Paré's court was caught stealing fine silver cutlery, and was condemned to be hanged. The cook agreed to be poisoned, on the conditions that he would be given a bezoar straight after the poison and go free in case he survived. The stone did not cure him, and he died in agony seven hours after being poisoned. Thus Paré had proved that bezoars could not cure all poisons.[9]

Forensics

Paré's writings further include the results of his methodical studies on the effects of violent death on internal organs.[10][11] He also created and wrote, Reports in Court,[12] a procedure on the writing of legal reports in relation to medicine.[13] His writings and instructions are known to be the beginning of modern forensic pathology.[10][11]

Prostheses

Paré contributed both to the practice of surgical amputation and to the design of limb prostheses.[14][15] He also invented some ocular prostheses,[16] making artificial eyes from enameled gold, silver, porcelain and glass.

See also

References

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Poirier, Ambroise Paré, Paris, 2006, p. 42.

- ↑ In 1522, near Metz, a citizen had been pierced by twelve sword thrusts and was left to die; but Paré was able to treat him: "I was his doctor, pharmacist, surgeon and cook: I bandaged him until the end of the treatment, and God healed him." (Jean-Michel Delacomptée, Ambroise Paré, La main savante, Gallimard, 2007, pp. 166–167.) originally from Voyage d'Allemagne, Œuvres, t. III, p. 698. Elsewhere Paré also wrote: "Preservation lies more in the divine providence than in the physician or surgeon’s advice." (Jean-Pierre Poirier, Ambroise Paré, Paris, 2006, p. 33.)

- ↑ Ambroise Paré, "A Surgeon in the Field," in The Portable Renaissance Reader, James Bruce Ross and Mary Martin McLauglin, eds. (New York, Viking Penguin, 1981): 558–563.

- ↑ Paget, Stephen (1897). Ambroise Paré and his times, 1510-1590. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 26. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ News.nationalgeographic.com

- ↑ Neonatology.org

- ↑ Fabricio Cardenas, Vieux papiers des Pyrénées-Orientales, Ambroise Paré à Perpignan en 1542 , 13 February 2015

- ↑ "The lancet and the gum-lancet: 400 years of teething babies", Ann Dally, The Lancet, Volume 348, Issue 9043, 21–28 December 1996, Pages 1710–1711

- ↑ Thompson, C. J. S. (1924) Poison Mysteries in History, Romance and Crime J.B. Lippincott, New York, pages 61–62, OCLC 1687048

- 1 2 "History of Forensics". The Discovery Channel. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- 1 2 "Forensic History Timeline". American College of Forensic Examiners. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ↑ "History of Crime". Crimeline. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ↑ Thomas Spencer Baynes (1888). The Encyclopaedia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature, Volume 15. H.G. Allen. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ↑ "Prostheses by Ambroise Paré" drawings

- ↑ Thurston, Alan J. (2007) "Paré and prosthetics: the early history of artificial limbs" ANZ Journal of Surgery 77(12): pp. 1114–1119, doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04330.x

- ↑ Snyder, Charles (1963) "Ambroise Pare and Ocular Prosthesis" Archives of Ophthalmology 70(1): pp. 130–132

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ambroise Paré. |

- Statue of Ambroise Paré, Place du Jet d'eau in Laval, France

- Page through a virtual copy of Paré's Oeuvres

- Stephen Paget (1897), Ambroise Paré and His Times, 1510–1590, G.P. Putnam's sons. Bezoar stone story on pages 186–7. Paré not a huguenot on page 84

- Famous Surgeons in History