Amish religious practices

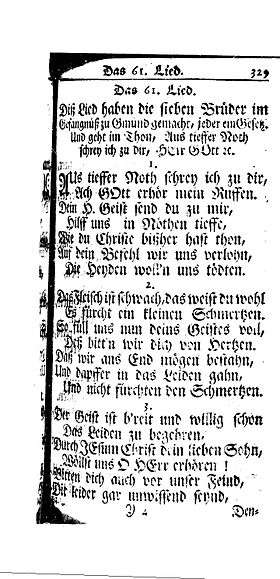

The Old Order Amish typically have worship services every second Sunday in private homes. The typical district has 80 adults and 90 children under age 19.[1] Worship begins with a short sermon by one of several preachers or the bishop of the church district, followed by scripture reading and prayer (this prayer is silent in some communities), then another, longer sermon. The service is interspersed with hymns sung without instrumental accompaniment or harmony. This is meant to put the emphasis on what is said, not how it is being said. Many communities use an ancient hymnal known as the Ausbund. The hymns contained in the Ausbund were generally written in what is referred to as Early New High German, a predecessor to modern Standard German.

Singing is usually very slow, and a single hymn may take 15 minutes or longer to finish. In Old Order Amish services, scripture is either read or recited from the German translation of Martin Luther. Worship is followed by lunch and socializing. Church services are conducted in a mixture of Standard German (or 'Bible Dutch') and Pennsylvania German. Amish ministers and deacons are selected by lot[2] out of a group of men nominated by the congregation. They serve for life and have no formal training. Amish bishops are similarly chosen by lot from those selected as preachers. The Old Order Amish do not work on Sunday, except to care for animals. Some congregations may forbid making purchases or exchanging money on Sundays. Also, within some congregations a motor vehicle and driver may not be hired on Sunday, except in an emergency.[3]

Congregations and districts

The majority of Old Order Amish congregations do not have church buildings, but hold worship services in private homes. Thus they are sometimes called "House Amish." This practice is based on a verse from the New Testament: "The God who made the world and all things in it, since He is Lord of heaven and earth, does not dwell in temples made with hands…" (Acts 17:24). In addition, the early Anabaptists, from whom the Amish are descended, were religiously persecuted, and it may have been safer to pray in the privacy of a home.

Unlike other church congregations whose membership is based on whoever visits, stays and joins, the Amish congregations are based on the physical location of their residence. Contiguous properties are encircled with a congregation's physical boundary. Each congregation is made up of 25–30 neighboring farm or related families whose membership in the congregation in which their farm is located is the only congregation available for membership. Accordingly, each member is also a neighbor. There is no "church hopping" from church to church like modern Protestant churches, and relationships are assumed to be long-term. With long-term neighbor relationships as the norm, extending over time to include multiple generations as members, the implications have major impacts on relationships. Conflict resolution, gossip, grudges, neighborliness, all work to cement relationships vastly different than the socially mobile Protestant church culture.

Congregations meet every other week for the entire Sunday at a member family's farm. Each member family rotates as host so that each year each member family serves as host. This practice conforms to the Biblical teaching to forsake not the assembling of ourselves together, as the manner of some is.[4] Congregations own common property in the form of tables, chairs, and wagons to transport them from farm to farm every other week. In interleaving weeks, time is available to visit a Sunday with family, neighbors and friends in and outside the congregation of their residence and membership.

Each congregation's leadership is made up with one of the members serving as bishop, one as deacon, and one as secretary. Each congregation's leadership, over time, differs from other congregations within enjoining districts in teaching, doctrine, protocol, dress, routines. Congregation leaders meet with other congregation leaders within the same district from time to time and compare needs, problems, teachings, etc.

Humility

Two key concepts for understanding Amish practices are their rejection of Hochmut (pride, arrogance, haughtiness) and the high value they place on Demut (humility) and Gelassenheit (calmness, composure, placidity), often translated as "submission" or "letting-be". Gelassenheit is perhaps better understood as a reluctance to be forward, to be self-promoting, or to assert oneself. The Amish's willingness to submit to the "Will of God", expressed through group norms, is at odds with the individualism so central to the wider American culture. The Amish anti-individualist orientation is the motive for rejecting labor-saving technologies that might make one less dependent on community. Modern innovations like electricity might spark a competition for status goods, or photographs might cultivate personal vanity.

Separation from the world

The Amish consider the Bible a trustworthy guide for living but do not quote it excessively. To do so would be considered a sinful showing of pride. Separation from the rest of society is based on being a "chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people" (1 Peter 2:9), not being "conformed to this world" (Romans 12:2), avoiding the "love [of] the world or the things in the world" (1 John 2:15) and the belief that "friendship with the world is enmity with God" (James 4:4).[5]

Both out of concern for the effect of absence from the family life, and to minimize contact with outsiders, many Old Order Amish prefer to work at home. Increased prices of farmland and decreasing revenues for low-tech farming have forced many Amish to work away from the farm, particularly in construction and manufacturing, and, in those areas where there is a significant tourist trade, to engage in shop work and crafts for profit. The Amish are ambivalent about both the consequences of this contact and the commoditization of their culture. The decorative arts play little role in authentic Amish life (though the prized Amish quilts are a genuine cultural inheritance, unlike hex signs), and are in fact regarded with suspicion, as a field where egotism and a display of vanity can easily develop.

Amish lifestyles vary between, and sometimes within, communities. These differences range from profound to minuscule. Some of the more liberal Beachy Amish congregations, which permit automobiles, may mandate that automobiles be painted black. In some communities, various Old Order groups may vary over the type of suspenders males are required to wear, if any, or how many pleats there should be in a bonnet, or if one should wear a bonnet at all. Groups in fellowship can intermarry and have communion with one another, an important consideration for avoiding problems that may result from genetically closed populations. Thus minor disagreements within communities, or within districts, over dairy equipment or telephones in workshops may or may not splinter churches or divide multiple communities.

Some of the strictest Old Order Amish groups are the Nebraska Amish ("White-top" Amish), Troyer Amish, and the Swartzentruber Amish.[6] Most Old Order Amish people speak Pennsylvania German in the home, with the exception of several areas in the Midwest, where a variety of Swiss German may be used. In Beachy Amish settings, the use of English in church is the norm, but with some families continuing to use Pennsylvania German, or a variety of Swiss German, at home.

Shunning

Members who break church rules may be called to confess before the congregation. Those who will not correct their behavior are excommunicated. Excommunicated members are shunned to shame the individual into returning to the church. Members may interact with and even help a shunned person, but may not accept anything, like a handshake, payment, or automobile ride, directly from the wayward person. Some communities have split in the last century over how they apply this practice of "Meidung". This form of discipline is recommended by the bishop after a long process of working with the individual and must be unanimously approved by the congregation.[7] Excommunicated members will be accepted back into the church if they return and confess their wrongdoing

Generally, the Amish hold communion in the spring and the autumn, and not necessarily during regular church services. Communion is only held open to those who have been baptized. As with regular services, the men and women sit separately. The ritual ends with members washing and drying each other's feet.[9]

Baptism

The practice of believer's baptism is the Amish's admission into the church. They and other Anabaptists do not accept that a child can be meaningfully baptized. Their children are expected to follow the will of their parents in all issues, but when they come of age, they must choose to make an adult, permanent commitment to God and the community. Those who come to be baptized sit with one hand over their face, representing humility and submission to the church. The candidates are asked three questions:

- 1. Can you renounce the devil, the world, and your own flesh and blood?

- 2. Can you commit yourself to Christ and His church, and to abide by it and therein to live and to die?

- 3. And in all order (Ordnung) of the church, according to the word of the Lord, to be obedient and submissive to it and to help therein?[10]

Typically, a deacon ladles water from a bucket into the bishop's cupped hands, which drips over the candidate's head. Then the bishop blesses the young men and greets them into the fellowship of the church with a holy kiss. The bishop's wife similarly blesses and greets the young women.[10]

Baptism is a permanent vow to follow the church and the Ordnung. Since the church leaders only perform weddings for members, baptism is an incentive for young couples with romantic ties, funneling them toward the church. Girls tend to join at an earlier age than boys. About five or six months before the ceremony, classes are held to instruct the candidates, teaching them the strict implications of what they are about to profess. The Saturday before baptism, they are given their last chance to withdraw. The difficulty of walking the narrow path is emphasized, and the applicants are instructed it is better not to vow than to make the vow and break it later on.[11]

Membership is taken seriously. Those who join the church, and then later leave, may be shunned by their former congregation and their families. Those who choose to not join can continue to relate freely with their friends and family. Church growth occurs through having large families and by retaining those children as part of the community. The Old Order Amish do not proselytize, as a rule. Conversion to the Amish faith is rare, but does occasionally occur as in the case of historian David Luthy.[12]

Funerals

Funeral practices vary across Amish settlements. But all of them reflect the core Amish values of simplicity, humility, and mutual aid.[13] The Amish hold funeral services in the home rather than using the funeral parlor. Instead of referring to the deceased with stories of his life, and eulogizing him, services tend to focus on the creation story and biblical accounts of resurrection. In Adams County, Indiana, and Allen County, Indiana, the Old Order Amish use only wooden grave markers that eventually decay and disappear. The same is true of other, smaller communities that have their roots in these two counties.

After the funeral, the hearse carries the casket to the cemetery for a reading from the Bible; perhaps a hymn is read (rather than sung) and the Lord's Prayer is recited. The Amish usually, but not always, choose Amish cemeteries, and purchase gravestones that are uniform, modest, and plain; in recent years, these have been inscribed in English. The bodies of both men and women are dressed in white clothing by family members of the same sex, with women in the white cape and apron of their wedding outfit.[14] After a funeral, the community gathers together to share a meal.

References

- ↑ Based on data from Lancaster county collected. Kraybill (2001), p. 91.

- ↑ Based on Acts 1:23–26

- ↑ Kauffman (2001), p. 125.

- ↑ Hebrews 10:25

- ↑ Kraybill (2001), pp. 37 and 45.

- ↑ Kraybill (2000), p. 68.

- ↑ Kraybill (2001), pp. 131–141

- ↑ Hostetler p. 228

- ↑ Brad Igou (1995). "Amish Religious Traditions". Amish Country News. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- 1 2 Kraybill (2001), pp. 116–119.

- ↑ The Riddle of Amish Culture | Kraybill | p. 116–7

- ↑ The sociology of Canadian Mennonites, Hutterites, and Amish: a …, Volume 2 by Donovan E. Smucker, pg 147

- ↑ "Funerals". Amish Studies. Young Center for Anabaptist & Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College.

- ↑ Kraybill (2001) p. 159.