An American in Paris

An American in Paris is a jazz-influenced symphonic poem by the American composer George Gershwin, written in 1928. Inspired by the time Gershwin had spent in Paris, it evokes the sights and energy of the French capital in the 1920s and is one of his best-known compositions.

Gershwin composed An American in Paris on commission from the conductor Walter Damrosch. He scored the piece for the standard instruments of the symphony orchestra plus celesta, saxophones, and automobile horns. He brought back some Parisian taxi horns for the New York premiere of the composition, which took place on December 13, 1928, in Carnegie Hall, with Damrosch conducting the New York Philharmonic.[1] Gershwin completed the orchestration on November 18, less than four weeks before the work's premiere.[2]

Gershwin collaborated on the original program notes with the critic and composer Deems Taylor, noting that: "My purpose here is to portray the impression of an American visitor in Paris as he strolls about the city and listens to various street noises and absorbs the French atmosphere." When the tone poem moves into the blues, "our American friend ... has succumbed to a spasm of homesickness." But, "nostalgia is not a fatal disease." The American visitor "once again is an alert spectator of Parisian life" and "the street noises and French atmosphere are triumphant."

Background

Gershwin was attracted by Maurice Ravel's unusual chords. After transatlantic letters back and forth as to whether Ravel took students and how much he charged, Ravel looked at Gershwin's prior year earnings and sent a telegram to Gershwin jokingly saying he (Ravel) should study with Gershwin!...but he accepted him as a student. Gershwin went to Paris in 1926 ready to study and to enjoy his first trip to Paris. After his initial student audition with Ravel turned into a sharing of musical theories, Ravel said he couldn't teach him but he would send a letter referring him to Nadia Boulanger. While the studies were cut short, that 1926 trip resulted in the initial version of An American in Paris written as a 'thank you note' to Gershwin's hosts, Robert and Mabel Shirmer. Gershwin called it "a rapsodic ballet' written so freely and much more modern than his prior works.

Gershwin strongly encouraged Ravel to come to the United States for a tour, something Ravel had been reluctant to do. To this end, upon his return to New York, Gershwin joined the efforts of Ravel's friend Robert Schmitz, a pianist Ravel had met during the War to urge Ravel to tour the U.S. Schmitz was the head of Pro Musica promoting Franco-American musical relations and was able to offer Ravel a $12,000 fee for the tour, an enticement Gershwin knew would be important to Ravel.

Gershwin greeted Ravel in New York in February 1928 at the start of Ravel's U.S. Tour, and joined Ravel again later in the tour in Los Angeles. After a lunch together with Chaplin in Beverly Hills, Ravel was persuaded to perform an unscheduled 'house concert' in a friend's music salon, performing among kindred spirits.

Ravel's tour reignited Gershwin's desire to return to Paris which he did in March 1928. Ravel's high praise of Gershwin in an introductory letter to Boulanger caused Gershwin to seriously consider taking much more time to study abroad in Paris. Yet after playing for her, she told him she could not teach him. Nadia Boulanger gave Gershwin basically the same advice she gave all of her accomplished master students "Don't copy others; be yourself." In this case "Why try to be a second rate Ravel when you are already a first rate Gershwin?" This did not set Gershwin back, as his real intent abroad was to complete a new work based on Paris and perhaps a second rhapsody for piano and orchestra to follow his Rhapsody in Blue. Paris at this time hosted many expatriate writers: among them Ezra Pound, W. B. Yeats, Ernest Hemingway; and artist Pablo Picasso.[3]

Composition

Gershwin based An American in Paris on a melodic fragment called "Very Parisienne", written in 1926 on his first visit to Paris as a gift to his hosts, Robert and Mabel Schirmer. He described the piece as a "rhapsodic ballet" because it was written freely and is more modern than his previous works. Gershwin explained in Musical America, "My purpose here is to portray the impressions of an American visitor in Paris as he strolls about the city, listens to the various street noises, and absorbs the French atmosphere."

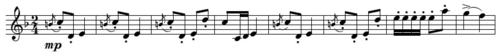

The piece is structured into five sections, which culminate in a loose ABA format. Gershwin's first A episode introduces the two main "walking" themes in the "Allegretto grazioso" and develops a third theme in the "Subito con brio". The style of this A section is written in the typical French style of composers Claude Debussy and Les Six. This A section featured duple meter, singsong rhythms, and diatonic melodies with the sounds of oboe, English horn, and taxi horns. The B section's "Andante ma con ritmo deciso" introduces the American Blues and spasms of homesickness. The "Allegro" that follows continues to express homesickness in a faster twelve-bar blues. In the B section, Gershwin uses common time, syncopated rhythms, and bluesy melodies with the sounds of trumpet, saxophone, and snare drum. "Moderato con grazia" is the last A section that returns to the themes set in A. After recapitulating the "walking" themes, Gershwin overlays the slow blues theme from section B in the final “Grandioso.”

Instrumentation

An American in Paris is scored for 3 flutes (3rd doubling on piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets in B-flat, bass clarinet in B-flat, 2 bassoons, 4 horns in F, 3 trumpets in B-flat, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, bass drum, triangle, wood block, cymbals, low and high tom-toms, xylophone, glockenspiel, celesta, 4 taxi horns labeled as A, B, C and D with circles around them, alto saxophone/soprano saxophone, tenor saxophone/soprano saxophone/alto saxophone, baritone saxophone/soprano saxophone/alto saxophone, and strings. Although most modern audiences have heard the taxi horns using the notes A, B, C and D, it has recently come to light[4] that Gershwin's intention was to have used the notes A♭4, B♭4, D5, and A4.[5] It is likely that in labeling the taxi horns as A, B, C and D with circles, he may have been referring to the use of the four different horns and not the notes that they played.

The revised edition by F. Campbell-Watson calls for three saxophones, alto, tenor and baritone. In this arrangement the soprano and alto doublings have been rewritten to avoid changing instruments.

William Daly arranged the score for piano solo which was published by New World Music in 1929.

Response

Gershwin did not particularly like Walter Damrosch's interpretation at the world premiere of An American in Paris. He stated that Damrosch's sluggish, dragging tempo caused him to walk out of the hall during a matinee performance of this work. The audience, according to Edward Cushing, responded with "a demonstration of enthusiasm impressively genuine in contrast to the conventional applause which new music, good and bad, ordinarily arouses." Critics believed that An American in Paris was better crafted than his lukewarm Concerto in F. Some did not think it belonged in a program with classical composers César Franck, Richard Wagner, or Guillaume Lekeu on its premiere. Gershwin responded to the critics, "It's not a Beethoven Symphony, you know... It's a humorous piece, nothing solemn about it. It's not intended to draw tears. If it pleases symphony audiences as a light, jolly piece, a series of impressions musically expressed, it succeeds."

Preservation status

On September 22, 2013, it was announced that a musicological critical edition of the full orchestral score will be eventually released. The Gershwin family, working in conjunction with the Library of Congress and the University of Michigan, are working to make scores available to the public that represent Gershwin's true intent. It is unknown if the critical score will include the four minutes of material Gershwin later deleted from the work (such as the restatement of the blues theme after the faster 12 bar blues section), or if the score will document changes in the orchestration during Gershwin's composition process.[6]

The score to An American in Paris is currently scheduled to be issued first in a series of scores to be released. The entire project may take 30 to 40 years to complete, but An American in Paris will be an early volume in the series.[7][8]

Two Urtext Editions of the work have been published by the German publisher B-Note Music in 2015. The changes made by Campbell-Watson have been withdrawn in both editions. In the extended Urtext, 120 bars of music have been re-integrated. Conductor Walter Damrosch had cut them shortly before the first performance.[9]

Recordings

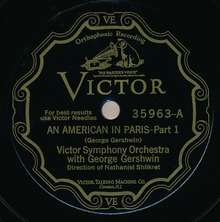

An American in Paris has been frequently recorded. The first recording was made for RCA Victor in 1929 with Nathaniel Shilkret conducting the Victor Symphony Orchestra, drawn from members of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Gershwin was on hand to "supervise" the recording; however, Shilkret was reported to be in charge and eventually asked the composer to leave the recording studio. Then, a little later, Shilkret discovered there was no one to play the brief celesta solo during the slow section, so he hastily asked Gershwin if he might play the solo; Gershwin said he could and so he briefly participated in the actual recording. This recording is believed to use the taxi horns in the way that Gershwin had intended using the notes A flat, B flat, a higher C and a lower D.[4] The radio broadcast of the September 8, 1937 Hollywood Bowl George Gershwin Memorial Concert, in which An American in Paris, also conducted by Shilkret, was second on the program, was recorded and was released in 1998 in a two-CD set. Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Orchestra recorded the work for RCA Victor, including one of the first stereo recordings of the music. In 1945, Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra recorded the music in Carnegie Hall, one of the few commercial recordings Toscanini made of music by an American composer. The Seattle Symphony also recorded a version in 1990 of Gershwin's original score, before he made numerous edits resulting in the score as we hear it today.[10] Harry James released a version of the blues section on his 1953 album One Night Stand, recorded live at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago (Columbia GL 522 and CL 522).

Use in film

In 1951, MGM released the musical film An American in Paris, featuring Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron. Winning the 1951 Best Picture Oscar and numerous other awards, the film was directed by Vincente Minnelli, featured many tunes of Gershwin, and concluded with an extensive, elaborate dance sequence built around the An American in Paris symphonic poem (arranged for the film by Johnny Green), costing $500,000.

References

- ↑ Georghe Gershwin. "Rhapsody in Blue for Piano and Orchestra : An American in Paris" (PDF). Nyphil.prg. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ↑ Richard Freed. "An American in Paris: About the Work". The Kennedy Center. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ LSRI Archives Oral Interview Anita Loos and Mary Anita Loos October 1979 re: letters and Ravel's telegram to Gershwin

- 1 2 "Have We Been Playing Gershwin Wrong for 70 Years?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ↑ "1929 Gershwin Taxi Horn Photo Clarifies Mystery". University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance. 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ↑ "New, critical edition of George and Ira Gershwin's works to be compiled | PBS NewsHour". Pbs.org. 2013-09-14. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ↑ "The Editions » Gershwin". Music.umich.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ↑ "Musicology Now: George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition". Musicologynow.ams-net.org. 2013-09-17. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ↑ "An American in Paris Urtext". Bnote.de. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- ↑ Bargreen, Melinda (1990-06-28). "Entertainment & the Arts | Recordings | Seattle Times Newspaper". Community.seattletimes.nwsource.com. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

Further reading

- Rimler, Walter. George Gershwin – An Intimate Portrait. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 2009. 29–33.

- Pollack, Howard. George Gershwin – His Life and Work. Berkeley, University of California Press, 2006. 431–42.

External links

- An American in Paris: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- 1944 recording by the New York Philharmonic conducted by Artur Rodziński

- An American in Paris on YouTube, New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein, 1959