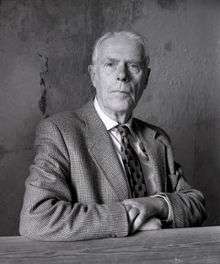

Anthony Powell

| Anthony Powell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Anthony Dymoke Powell 21 December 1905 Westminster, England |

| Died |

28 March 2000 (aged 94) Frome, Somerset |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Notable works | A Dance to the Music of Time |

| Spouse | Lady Violet Pakenham |

Anthony Dymoke Powell CH CBE (/ˈpoʊəl/ POH-əl;[1] 21 December 1905 – 28 March 2000) was an English novelist best known for his twelve-volume work A Dance to the Music of Time, published between 1951 and 1975.

Powell's major work has remained in print continuously and has been the subject of TV and radio dramatisations. In 2008, The Times newspaper named Powell among their list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".[2]

Biography

Powell was born in Westminster, England, to Philip Lionel William Powell and Maud Mary Wells-Dymoke. His father was an officer in the Welsh Regiment. His mother came from a land-owning family in Lincolnshire. Because of his father's career and World War I, the family moved several times, and mother and son sometimes lived apart from Powell's father.

Powell attended Gibbs's pre-prep day-school for a brief time. He was then sent to New Beacon School near Sevenoaks, which was popular with military families. Early in 1919, Powell passed the Common Entrance Examination for Eton where he started that autumn. There he made a friend of a fellow pupil, Henry Yorke, later to become known as the novelist Henry Green.

At Eton, Powell spent much of his spare time at the Studio, where a sympathetic art master encouraged him to develop his talent as a draughtsman and his interest in the visual arts. In 1922 he became a founding member of the Eton Society of Arts. The Society's members produced an occasional magazine called The Eton Candle.

In the autumn of 1923, Powell went up to Balliol College, Oxford. Soon after his arrival he was introduced to the Hypocrites Club. Outside that club he came to know Maurice Bowra, then a young don at Wadham College. During his third year Powell lived out of college, sharing rooms with Henry Yorke. Powell travelled on the Continent during his holidays. He was awarded a third-class degree at the end of his academic years.

He married Lady Violet Pakenham (1912–2002),[3] sister of Lord Longford, on 1 December 1934 at All Saints, Ennismore Gardens, Knightsbridge. Powell and his wife relocated to 1 Chester Gate in Regent's Park, London, where they remained for seventeen years.

Powell's first son, Tristram, was born in April 1940, but Powell and his wife spent most of the war years apart. A second son, John, was born in January 1946.[4]

Powell was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1956, and in 1973 he declined an offer of knighthood. He was appointed Companion of Honour (CH) in 1988. He served as a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery from 1962 to 1976.[5] With Lady Violet, he travelled to the United States, India, Guatemala, Italy, and Greece.

Anthony Powell died at The Chantry, in Frome, somerset, on 28 March 2000.

Work

Powell came to work in London during the autumn of 1926 and lived at various London addresses for the next 25 years. He worked in a form of apprenticeship at the publishers Gerald Duckworth and Company in Covent Garden, leaving their employ in 1932 after protracted negotiations about title, salary, and working hours. He next took a job as a script writer at the Warner Brothers Studio in Teddington, where he remained for six months.[6] He made an abortive attempt to find employment in Hollywood as a screenwriter in 1937. He next found work reviewing novels for The Daily Telegraph and memoirs and autobiographies for The Spectator.

Upon the outbreak of World War II, Powell joined his regiment as a Second Lieutenant at the age of 34, more than ten years older than most of his fellow subalterns, not at all well prepared and lacking in experience. His superiors found uses for his talents, resulting in a series of transfers that brought him special training courses designed to produce a nucleus of officers to deal with the problems of military government after the Allies had defeated the Axis powers. He eventually secured an assignment with the Intelligence Corps and additional training. His military career continued with assignment to the War Office in Whitehall, where he was attached to the section known as Military Intelligence (Liaison), and later—for a short time—to the Cabinet Office to serve on the Secretariat of the Joint Intelligence Committee, securing promotions along the way.

Returning to Military Intelligence (Liaison), in the War Office, he had responsibility for dealings with the Czechs, later with the Belgians and Luxembourgers, and later still the French. In November 1944, Powell acted as assistant escorting officer to a group of fourteen Allied military attachés taken to France and Belgium to see something of the campaign.

After his demobilisation at the end of the war, writing became his sole career.

Social life

Upon his arrival in London, part of Powell's social life developed around attendance at formal debutante dances at houses in Mayfair and Belgravia.

He renewed acquaintance with Evelyn Waugh, whom he had known at Oxford and was a frequent guest for Sunday supper at Waugh's parents' house. Waugh introduced him to the Gargoyle Club, which gave him experience in London's Bohemia.

He came to know the painters Nina Hamnett and Adrian Daintrey, who were neighbours in Fitzrovia, and the composer Constant Lambert, who remained a good friend until Lambert's death in 1951.

Despite a holiday trip to the Soviet Union in 1936, he remained unsympathetic to the popular-front, Leftist politics of many of his literary and critical contemporaries. A confirmed Tory, Powell maintained a certain scepticism. He was wary of right-wing groups and suspicious of inflated rhetoric.[7]

Writing

Powell's first novel, Afternoon Men, was published by Duckworth in 1931, with Powell supervising its production himself. The same firm published his next three novels, two of them after Powell had left the firm. During his time in California Powell contributed several articles to the magazine Night and Day, edited by Graham Greene. Powell wrote a few more occasional pieces for the magazine until it ceased publication in March 1938. Powell completed his fifth novel, What's Become of Waring, in late 1938 or early 1939. After being turned down by Duckworth, it was published by Cassell in March of that year. The book sold fewer than a thousand copies.

Anticipating the difficulties of creative writing during wartime, Powell began to assemble material for a biography of the seventeenth-century writer John Aubrey. His army career, it turned out, forced him to postpone even that biographical work. When the war ended Powell resumed work on Aubrey, completing the manuscript of John Aubrey and His Friends in May 1946, though it only appeared in 1948 after difficult negotiations and arguments with publishers. He then edited a selection of Aubrey's writings that appeared the following year.

Powell returned to novel writing and began to ponder a long novel-sequence. Over the next 30 years, he produced his major work: A Dance to the Music of Time. Its twelve novels have been acclaimed by such critics as A. N. Wilson and fellow writers including Evelyn Waugh and Kingsley Amis as among the finest English fiction of the twentieth century. Auberon Waugh dissented, calling it "tedious and overpraised—particularly by literary hangers-on".[8] Long-time friend V. S. Naipaul cast similar doubts regarding the work, if not the Powell oeuvre. Naipaul described his sentiments after a long-delayed review of Powell's work following the author's death this way: "it may be that our friendship lasted all this time because I had not examined his work".[9] While often compared to Proust, others find the comparison "obvious, although superficial."[10] Its narrator's voice is more like the participant-observer of The Great Gatsby than that of Proust's self-regarding narrator.[11] Powell was awarded the 1957 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for the fourth volume, At Lady Molly's. The eleventh volume, Temporary Kings, received the W.H. Smith Prize in 1974.[12] The cycle of novels, narrated by a protagonist with experiences and perspectives similar to Powell's own, follows the trajectory of the author's own life, offering a vivid portrayal of the intersection of bohemian life with high society between 1921 and 1971.

The title of the multi-volume series is taken from the painting of the same name by Poussin, which hangs in the Wallace Collection. Its characters, many modelled loosely on real people,[13] surface, vanish and reappear throughout the sequence. It is not, however, a roman à clef. The characters are drawn from the upper classes, their marriages and affairs, and their bohemian acquaintances.

In parallel with his creative writing, Powell served as the primary fiction reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement. He served as Literary Editor of Punch from 1953 to 1959. From 1958 to 1990, he was a regular reviewer for The Daily Telegraph, resigning after a vitriolic personal attack on him by Auberon Waugh appeared in that newspaper. He also reviewed occasionally for The Spectator.

He published two more novels, O, How the Wheel Becomes It! (1983) and The Fisher King (1986). He reprinted many of his book reviews in two volumes of critical essays, Miscellaneous Verdicts (1990) and Under Review (1992). Several volumes of Journals, covering the years 1982 to 1992, appeared between 1995 and 1997. His Writer's Notebook was published posthumously in 2001, and a third volume of critical essays, Some Poets, Artists, and a Reference for Mellors, appeared in 2005.

Alan Furst, author of insightful books of espionage, has noted of Powell, "Powell does everything a novelist can do, from flights of aesthetic passion to romance to comedy high and low. His dialogue is extraordinary; often terse, pedestrian and perfect, each character using three or four words. Anthony Powell taught me to write; he has such brilliant control of the mechanics of the novel."[14]

Recognition

Dance was adapted by Hugh Whitemore for a TV mini-series during the autumn of 1997, and broadcast in the UK on Channel 4. The novel sequence was earlier adapted by Graham Gauld and Frederick Bradnum for a BBC Radio 4 26-part series broadcast between 1978 and 1981. In the radio version the part of Jenkins as narrator was played by Noel Johnson. A second radio dramatisation by Michael Butt was broadcast during April and May 2008.

A centenary exhibition in commemoration of Powell's life and work was held at the Wallace Collection, London, from November 2005 to February 2006. Smaller exhibitions were held in 2005 and 2006 at Eton College, Cambridge University, the Grolier Club in New York City, and Georgetown University in Washington, DC.

In 1995, he was awarded an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Letters) from the University of Bath.[15]

Bibliography

A Dance to the Music of Time, the twelve-volume series of novels:

- A Question of Upbringing (1951)

- A Buyer's Market (1952)

- The Acceptance World (1955)

- At Lady Molly's (1957)

- Casanova's Chinese Restaurant (1960)

- The Kindly Ones (1962)

- The Valley of Bones (1964)

- The Soldier's Art (1966)

- The Military Philosophers (1968)

- Books Do Furnish a Room (1971)

- Temporary Kings (1973)

- Hearing Secret Harmonies (1975)

Partial bibliography of other novels, plays, and works:

- The Barnard Letters (1928)

- Afternoon Men (1931)

- Venusberg (1932)

- From a View to a Death (1933)

- "The Watr'y Glade", in The Old School: Essays by Divers Hands, ed. Graham Greene (1934)

- Agents and Patients (1936)

- What's Become of Waring (1939)

- John Aubrey and His Friends (1948)

- Two Plays: The Garden God, The Rest I'll Whistle (1971)

- O, How the Wheel Becomes It! (novel) (1983)

- The Fisher King (1986)

- A Writer’s Notebook, 2001

- Miscellaneous Verdicts. Writings on Writers 1946-1989, 1990

- Under Review. Further Writings on Writers 1946-1989, 1991

- Some Poets, Artists & ´A Reference for Mellors`, 2005

- The Acceptance of Absurdity. Anthony Powell & Robert Vanderbilt: Letters 1952 - 1963. Edited by John Saumarez Smith & Jonathan Kooperstein. Maggs Brothers, London 2011

Memoirs

- To Keep the Ball Rolling: Memoirs of Anthony Powell

- vol. 1, Infants of the Spring (1976)

- vol. 2, Messengers of Day (1978)

- vol. 3, Faces in My Time (1980)

- vol. 4, The Strangers All are Gone (1982)

A one-volume abridgment, called simply To Keep the Ball Rolling, was published in 1983.

Diaries

- Journals 1982–1986 (1995)

- Journals 1987–1989 (1996)

- Journals 1990–1992 (1997)

Notes

- ↑ Michael Barber, Anthony Powell: A Life (London: Duckworth Overlook, 2004), 291

- ↑ The 50 greatest British writers since 1945. 5 January 2008. The Times. Retrieved on 19 February 2010.

- ↑ Nicholas Birns, Understanding Anthony Powell (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2004), xiii–xiv

- ↑ Birns, 7

- ↑ Barber, 242–3

- ↑ Barber, 103

- ↑ Nicholas Birns, 312–4, 320–2; Barber, 46

- ↑ Alan Watkins, Brief Lives with Some Memoirs (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1982), 197

- ↑ V. S. Naipaul. A Writer's People 36–40, Knopf, 2007

- ↑ Compare Birns, ix, and Neil McEwan, Anthony Powell (NY: St. Martin's Press, 1991), 121–2

- ↑ Barber, 120, 211–2, 226, 231–2

- ↑ Literary Thing: "Book awards: WH Smith Literary Award", accessed 29 Dec. 2009

- ↑ Anthony Powell Society: The Anthony Powell Society

- ↑ Alan Furst "By the Book," New York Times May 29, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/01/books/review/alan-furst-by-the-book.html?hpw&rref=books&_r=0

- ↑ "Honorary Graduates 1989 to present". bath.ac.uk. University of Bath. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

Additional reading

- Barber, Michael. Anthony Powell: A Life, Duckworth Overlook, 2004. ISBN 0-7156-3049-0

- Birns, Nicholas. Understanding Anthony Powell, University of South Carolina Press, 2004. ISBN 1-57003-549-0

- Hitchens, Christopher: Anthony Powell: An Omnivorous Curiosity (Review of To Keep the Ball Rolling, in: Arguably. Essays by Christopher Hitchens, pp. 276 – 289, New York 2011 [first published in The Atlantic, June 2001]. ISBN 978-1-4555-0409-1

- Joyau, Isabelle: Investigating Powell's A Dance to the Music of Time, London 1994. ISBN 0-312-10670-X

- Kislinger, Peter: Review Article: Isabelle Joyau, Investigating Powell’s ´A Dance to the Music of Time´, London 1994, in: Anthony Powell Society Newsletter 3/Spring 2001 [originally published in German in: Sprachkunst, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1996/2]

- Roger K. Miller, "Author offers intelligent study of 'English Proust'", The Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 5 September 2004

- The Album of Anthony Powell’s 'Dance to the Music of Time' [Hardcover, with 224 illustrations], Anthony Powell (Preface), edited by Violet Powell, Introduction by John Bayley, London 1987.

- Selig, Robert: Time and Anthony Powell. A Critical Study, Cranbury 1991. ISBN 0-8386-3405-2

- Norman Shrapnel, "Anthony Powell", The Guardian, 30 March 2000

- Spurling, Hilary. Invitation to the Dance: A Guide to Anthony Powell's Dance to the Music of Time, Little Brown, 1977. ISBN 0-316-80900-4

- Tucker, James. The Novels of Anthony Powell, Columbia University Press, 1976. ISBN 0-231-04150-0

- Powell author page and archive at The London Review of Books

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anthony Powell |

- Michael Barber (Spring–Summer 1978). "Anthony Powell, The Art of Fiction No. 68". The Paris Review.

- "Archival material relating to Anthony Powell". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Anthony Dymoke Powell at the National Portrait Gallery, London