Arab television drama

Arab television drama or Arab soap opera (also known as "مسلسل", musalsal, plural musalsalat) is a television form of melodramatic serialized fiction.[1] The musalsalat are similar in style to Latin American telenovelas.[1] They are often historical epics about Islamic figures or love stories involving class conflict and intrigue.[1] The word musalsal literally means "chained, continuous".[2]

During the evenings of the month of Ramadan, after the Iftar meal is eaten to break the day's fast, families across much of the Arab world watch these special dramas on television.[3] Arab satellite channels broadcast the programs each night, drawing families who have gathered to break their fast.[4] Most musalselat are bundled into about 30 episodes, or about one episode for each night of Ramadan.[5] These television series are an integral part of the Ramadan tradition, the same way the hakawati, the storyteller who recounted tales and myths, was part of Ramadan nights in the past.[6]

According to the market research firm Ipsos, during the first two weeks of Ramadan 2011 television figures rose across the Middle East by 30%, and as many as 100 Arab soap operas and shows broadcast on state and private channels.[7] The Ramadan season has been compared to a month-long Super Bowl for its importance in the Arab world's television market.[7] During this period, television ratings remain high well into the night, and the cost of a 30-second advertisement during peak Ramadan viewing hours can be more than double the normal rate.[7] According to the Pan Arab Research Center, the amount spent in 2012 for Ramadan television advertising exceeded a forecast of US$420 million, out of an estimated $1.98 billion for the total Arab television advertising market for the same year.[8]

In 2012, YouTube has announced a new online channel specifically dedicated to showing Ramadan shows.[9]

Egypt

In 2012 Egyptian television channels had more than 50 soap operas on offer, for a combined production cost estimated at a record 1.18 billion Egyptian pounds.[3]

Kuwait

Kuwaiti soap operas are the most-watched soap operas in the Gulf region.[10][11] They are the second most-watched soap operas in the Arab world (after Egypt).[10] Although usually performed in the Kuwaiti dialect, they have been shown with success as far away as Tunisia.[12] Soap operas have become important national pastimes in Kuwait. They are most popular during the time of Ramadan, when families gather to break their fast. Most Gulf soap operas are based in Kuwait.[13][14] Darb El Zalag, Khalti Gmasha, and Ruqayya wa Sabika are among the most important television productions in the Gulf region.

Lebanon

Lebanese drama series lag significantly behind the more popular Syrian or Egyptian production, a lack of popularity thought to be caused primarily by weak scripts.[6] Lebanese series also face challenges because of low budgets and an absence of government support.[15] Because of the war in Syria, some Syrian production companies have relocated their projects to Lebanon.[16]

Syria

Syrian soap operas took off in the 1990s, when satellite-television access increased across the Arab world, and were watched by tens of millions of people from Morocco to the Persian Gulf. As a consequence of the Syrian civil war, Syrian production companies have shelved new shows and viewers throughout the Arab world have called for a boycott of Syrian satellite channels. A tax break issued by the government has failed to revive the industry.[17] In 2010, some 30 Syrian soaps were aired during Ramadan, some only in Syria, but most on pan-Arab satellite channels.[18]

Syrian musalselat have become one of the country's most prized exports, and are very popular in the Persian Gulf countries.[5] Following the onset of the 2011 Syrian uprising, some have called for a boycott of Syrian musalselat.[5]

Many Syrian actors, producers and directors left the country; many film sets have been destroyed or made inaccessible by the fighting.[19] By 2014 only 20 Syrian series were being made, compared to the 40 produced in 2010.[19]

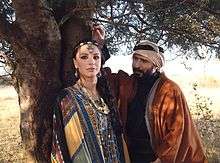

Jordan

Jordan produces a number of “Bedouin Soap Operas” that are filmed outdoors with authentic props.[20] The actors use Bedouin-accented Arabic to make the story feel more authentic. These musalsalat have become popular in Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

In musalsalat that center around traditional village life during the time period just before World War II. Oftentimes, these dramas are permeated by themes of tension between the traditional and modern ways of life with specific emphasis on the patriarchal systems and the role of women within them. Unique to this particular type of musalsal is the willingness of the shows’ creators to confront sensitive issues such as honor killing. Another musalsal genre is that of the historical drama. Topics of these shows range from pre-Islamic poets to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Many of these are joint productions by Jordanian, Syrian, and Persian Gulf region television producers. According to a survey of Jordan’s television viewers, 92.5% prefer watching Syrian dramas while 61.6% prefer Egyptian ones. This is compared to 26.6% who prefer watching Jordanian drama series.[21]

While the aforementioned musalsalat target a broader, Arabic-speaking audience, certain programs target Jordanians specifically. These shows tend to deal with social and political issues particular to present-day Amman. Acting in these programs, as well as Jordanian musalsalat in general, is often lauded as being superior to that of many Egyptian-produced soap operas.[22]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Ideas & Trends: Ramadan Nights; Traditions Old (Fasting) and New (Soap Operas)". New York Times. November 23, 2003.

- ↑ Salamandra, Christa. A New Old Damascus: Authenticity And Distinction In Urban Syria. pp. 169–170.

- 1 2 "Ramadan soap opera boom for Egypt". BBC News. 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Syrian Soap Opera Captivates Arab World". Washington Post. October 12, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Syria's Subversive Soap Operas". The Atlantic. Jul 29, 2011.

- 1 2 "Soap operas: a Ramadan family favorite". Saida Online. 2011-08-20.

- 1 2 3 "Ramadan TV: Your ultimate guide to the best of the month's television programmes". Gulf News. July 17, 2012.

- ↑ "Ramadan shows give TV revenue a big boost". The National. Aug 5, 2012.

- ↑ "YouTube Launches Ramadan TV". Nuqudy. 2012-07-18.

- 1 2 Fattahova, Nawara (26 March 2015). "First Kuwaiti horror movie to be set in 'haunted' palace". Kuwait Times.

- ↑ Al Mukrashi, Fahad (22 August 2015). "Omanis turn their backs on local dramas". Gulf News.

Kuwait’s drama industry tops other Gulf drama as it has very prominent actors and actresses, enough scripts and budgets, produces fifteen serials annually at least.

- ↑ Mansfield, Peter (1990). Kuwait: vanguard of the Gulf. Hutchinson. p. 113.

Some Kuwaiti soap operas have become extremely popular and, although they are usually performed in the Kuwaiti dialect, they have been shown with success as far away as Tunisia.

- ↑ "Big plans for small screens". BroadcastPro Me.

Around 90% of Khaleeji productions take place in Kuwait.

- ↑ Papavassilopoulos, Constantinos (10 April 2014). "OSN targets new markets by enriching its Arabic content offering". IHS Inc.

- ↑ "Lebanon's Ramadan TV series prepare to air". The Daily Star. July 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Made in Beirut: Syrians produce drama in Lebanon". Al Bawba. December 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Another Casualty of War: Soap Operas". New York Times. August 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Tough times for Syrian soap operas". Financial Times. July 14, 2011.

- 1 2 "A Syrian drama: The end of an affair". The Economist. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ "Artists concerned with decline in Jordan's Bedouin dramas". Al-Shorfa. 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Jordanian TV viewers prefer Syrian and Egyptian drama series over Jordanian ones". Arab Advisors Group. September 19, 2010.

- ↑ Shoup, John A. "Literature and Media." Culture and Customs of Jordan. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2006. 45–54. Print.

External links

- Most Popular Arabic-Language TV Series – IMDb

- Arab television: Battle of the box – The Economist

- The State of the Musalsal: Arab Television Drama and Comedy and the Politics of the Satellite Era By Marlin Dick

- Arab website for ramadan series and programs;–