Arthur Thomas Doodson

| Arthur Thomas Doodson | |

|---|---|

| Born |

31 March 1890 Boothstown Salford, Greater Manchester |

| Died | 10 January 1968 (aged 77) |

| Alma mater | University of Liverpool |

| Known for | Doodson numbers |

| Notable awards | Fellow of the Royal Society (1933)[1] |

Dr. Arthur Thomas Doodson (31 March 1890 – 10 January 1968) was a British oceanographer.

Biography

He was born at Boothstown, Salford, the son of cotton-mill manager Thomas Doodson. He was educated at Rochdale secondary school and then in 1908 entered the University of Liverpool, graduating in both chemistry (1911) and mathematics (1912). He was profoundly deaf and found it difficult to get a job but started with Ferranti in Manchester as a meter tester. During World War I he worked on the calculation of shell trajectories.[2]

In 1919 he moved to Liverpool to work on tidal analysis and became in 1929 the Associate Director of Liverpool Observatory and Tidal Institute. He then spent much of his life developing the analysis of tidal motions mainly in the oceans but also in lakes, and was the first to devise methods for shallow water as in estuaries. Tide height and current tables are of great importance to navigators, but the detailed motions are complex. The thorough analysis at which he excelled became the international standard for the study of tides and the production of tables through the method of determination of Harmonic Elements by Least-Square fitting to data observed at each place of interest. That is, by proper association of the astronomical phases, observations made at one time can enable predictions decades away with different astronomical phases.

Doodson published a major work on tidal analysis in 1921.[3] This was the first development of the tide generating potential (TGP) to be carried out in harmonic form: Doodson distinguished 388 tidal frequencies.[4] Doodson's analysis of 1921 was based on the then-latest lunar theory of E W Brown.[5] Doodson devised a practical system for specifying the different harmonic components of the tide-generating potential, see below for the Doodson Numbers.

Doodson also became involved in the design of tide-predicting machines, of which a widely used example was the "Doodson-Légé TPM".[5][6]

Among other works, Doodson was also co-author of the "Admiralty Manual of Tides", HMSO London 1941, (Doodson A T, and Warburg H D), reprinted in 1973.

Further biographical information is available from the National Oceanography Centre,[7] whose Liverpool facility was formerly the Liverpool Observatory and Tidal Institute, part of the UK Natural Environment Research Council, of which Doodson became director.[8]

In May, 1933 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society [9] His nomination reads

| “ | Distinguished for his work on tidal theory and on the interpretation of tidal observations, published partly in conjunction with J Proudman, and partly independently, in the Philosophical Transactions, the Royal Society's Proceedings, and elsewhere. Has personally greatly improved the resolution of the astronomical disturbing forces into their more important harmonic constituents. Has carried out the reduction of tidal observations of Antarctic expeditions. Made important contributions to Ballistics during the war, embodying great improvements in calculation, which have since been incorporated in the official Textbook of Anti-aircraft gunnery. Has done valuable work in Statistics, and in the computation of mathematical tables.[10] | ” |

In 1944, as the Allies prepared the invasion of Nazi-occupied France, they wanted to land at first light when it was low tide, so hidden obstacles could be seen. Doodson was enlisted to work out the tidal patterns using his mechanised calculators. His calculations revealed that 5–7 June would provide the best combination of full moon and ideal tidal conditions and D-Day duly took place on 6 June 1944.[11]

Doodson died at Birkenhead on 10 January 1968 and was buried at Flaybrick Hill Cemetery.[12] He had married twice. He married firstly in 1919 Margaret, daughter of J. W. Galloway, a tramways engineer of Halifax with whom he had a daughter, who died in 1936, and a son, whose mother died shortly after his birth in 1931. He married secondly in 1933 Elsie May, daughter of W. A. Carey, who survived him.[13]

Doodson numbers

In order to specify the different harmonic components of the tide-generating potential, Doodson devised a practical system which is still in use,[14] involving what are called the "Doodson numbers" based on the six "Doodson arguments" or Doodson variables.

The number of different tidal frequencies is large, but they can all be specified on the basis of combinations of small-integer multiples, positive or negative, of six basic angular arguments. In principle the basic arguments can possibly be specified in any of many ways; Doodson's choice of his six "Doodson arguments" has been widely used in tidal work. In terms of these Doodson arguments, each tidal frequency can then be specified as a sum made up of a small integer multiple of each one of the six arguments. The resulting six small integer multipliers effectively encode the frequency of the tidal argument concerned, and these are the Doodson numbers: in practice all except the first are usually biased upwards by +5 to avoid negative numbers in the notation. (In the case that the biased multiple exceeds 9, the system adopts X for 10, and E for 11.)[15]

The Doodson arguments are specified in the following way, in order of decreasing frequency:[15]

is 'Mean Lunar Time', the Greenwich Hour Angle of the mean Moon plus 12 hours.

is the mean longitude of the Moon.

is the mean longitude of the Sun.

is the longitude of the Moon's mean perigee.

is the negative of the longitude of the Moon's mean ascending node on the ecliptic.

or is the longitude of the Sun's mean perigee.

In these expressions, the symbols , , and refer to an alternative set of fundamental angular arguments (usually preferred for use in modern lunar theory), in which:-

- is the mean anomaly of the Moon (distance from its perigee).

- is the mean anomaly of the Sun (distance from its perigee).

- is the Moon's mean argument of latitude (distance from its node).

- is the Moon's mean elongation (distance from the sun).

It is possible to define several auxiliary variables on the basis of combinations of these.

In terms of this system, each tidal constituent frequency can be identified by its Doodson numbers. The strongest tidal constituent "M2" has a frequency of 2 cycles per lunar day, its Doodson numbers are usually written 255.555, meaning that its frequency is composed of twice the first Doodson argument, and zero times all of the others. The second strongest tidal constituent "S2" is due to the sun, its Doodson numbers are 273.555, meaning that its frequency is composed of twice the first Doodson argument, +2 times the second, -2 times the third, and zero times each of the other three.[16] This aggregates to the angular equivalent of mean solar time + 12 hours. These two strongest component frequencies have simple arguments for which the Doodson system might appear needlessly complex, but each of the hundreds of other component frequencies can be briefly specified in a similar way, showing in the aggregate the usefulness of the encoding.

A number of further examples can be seen in Theory of tides - Tidal constituents.

Usage

The usual analysis of a periodic function is in terms of Fourier series, that is, over a period of observation covering a time interval , the behaviour is analysed in terms of sinusoidal cycles having zero, one, two, three, etc. cycles in that period; in other words, a collection of frequencies all being a multiple of a particular fundamental frequency. If for example, measurements are made at equally-spaced times (thus at times , , , , , ) then there are observations, and the standard analysis provides an amplitude and phase figure for different frequencies having a period of , , , , etc.

In the case of tidal height (or similarly, tidal current) analysis of the situation is more complex. The frequency (or period) and phase of the forcing cycle is known from astronomical observations, and, there is not just one such frequency. The most important periods are the time of Earth's revolution, the completion of the moon's orbit around the earth, and Earth's orbit around the sun. Notoriously, none of these cycles are convenient multiples of each other. So, rather than proceed with one frequency and its harmonics, multiple frequencies are used.

Further, at each frequency, the influence is not exactly sinusoidal. For each fundamental frequency, the tidal force has the form - that is, an amplitude , an angular frequency , and a phase related to the choice of a zero time and the orientation of the astronomical attribute at that zero time. However, because the orbits are not circular, the magnitude of the force varies, and this variation is also modeled as a sinusoidal factor (or cosinusoidal), so that the amplitude is given by where represents the size of the variation around the average value of , the angular speed of this variation and its phase with regard to the time .

Because , a product of cosine terms can be split into the more convenient addition of two simple cosine terms, but having frequencies that are the sum and difference of the frequencies of the two product terms. Thus, where there was one cosine term whose amplitude varied, there are now three terms, with frequencies , , and . Further, although a variation is well represented by a cosine curve, it is not exactly represented by a cosine curve and so each spawns further terms that are multiples of its fundamental frequency just as in the simple Fourier analysis with one fundamental frequency where the variation being analysed is not exactly sinusoidal.

A determined analysis, such as Doodson excelled at, generates not just dozens of terms but hundreds (though many are tiny: tidal prediction might be performed with one or two dozen only) and the Doodson Number is a part of organising the collection. A particular component will be described with a name (M2, S2, etc.) and its angular frequency specified in terms of the Doodson Number, which specified what astronomical frequencies have been added and subtracted for that component. Thus, if , , , , , are the basic astronomical frequencies and a particular component has the frequency then its Doodson Number would be given as 0110-30 meaning . To avoid the typographical inconvenience of negative signs, the digit string might be presented with five added to each component so that fanciful example would be presented as 566525, except that the first digit may not have five added.

Precise usage depends on the precise choice of the component frequency definitions, whether or not five is added (if not, the string might be called an Indicative Doodson Number), and also, as some forces vary only slowly with time, a calculation once a month (say) might suffice so certain components might not be separated into additive terms following that variation.

Example

This is adapted from a script for the MATLAB system, and its main merit is that it actually does generate a suitable curve. In more general work, times and phases are usually referenced to GMT, and the prediction would be annotated with actual dates and times.

% Speed in degrees per hour for various Earth-Moon-Sun astronomical attributes, as given in Tides, Surges and Mean Sea-Level, D.T. Pugh.

clear EMS;

% T + s - h +15 w0: Nominal day, ignoring the variation followed via the Equation of Time.

EMS.T = +360/(1.0350)/24; %+14.492054485 w1: is the advance of the moon's longitude, referenced to the Earth's zero longitude, one full rotation in 1.0350 mean solar days.

EMS.s = +360/(27.3217)/24; % +0.5490141536 w2: Moon around the earth in 27.3217 mean solar days.

EMS.h = +360/(365.2422)/24; % +0.0410686388 w3: Earth orbits the sun in a tropical year of 365.24219879 days, not the 365.2425 in 365 + y/4 - y/100 + y/400. Nor with - y/4000.

EMS.p = +360/(365.25* 8.85)/24; % +0.0046404 w4: Precession of the moon's perigee, once in 8.85 Julian years: apsides.

EMS.N = -360/(365.25*18.61)/24; % -0.00220676 w5: Precession of the plane of the moon's orbit, once in 18.61 Julian years: negative, so recession.

EMS.pp= +360/(365.25*20942)/24; % +0.000001961 w6: Precession of the perihelion, once in 20942 Julian years.

% T + s = 15.041068639°/h is the rotation of the earth with respect to the fixed stars, as both are in the same sense.

% Reference Angular Speed Degrees/hour Period in Days. Astronomical Values.

% Sidereal day Distant star ws = w0 + w3 = w1 + w2 15.041 0.9973

% Mean solar day Solar transit of meridian w0 = w1 + w2 - w3 15 1

% Mean lunar day Lunar transit of meridian w1 14.4921 1.0350

% Month Draconic Lunar ascending node w2 + w5 .5468 27.4320

% Month Sidereal Distant star w2 .5490 27.3217 27d07h43m11.6s 27.32166204

% Month Anomalistic Lunar Perigee (apsides) w2 - w4 .5444 27.5546

% Month Synodic Lunar phase w2 - w3 = w0 - w1 .5079 29.5307 29d12h44m02.8s 29.53058796

% Year Tropical Solar ascending node w3 .0410686 365.2422 365d05h48m45s 365.24218967 at 2000AD. 365.24219879 at 1900AD.

% Year Sidereal Distant star .0410670 365.2564 365d06h09m09s 365.256363051 at 2000AD.

% Year Anomalistic Solar perigee (apsides) w3 - w6 .0410667 365.2596 365d06h13m52s 365.259635864 at 2000AD.

% Year nominal Calendar 365 or 366

% Year Julian 365.25

% Year Gregorian 365.2425

% Obtaining definite values is tricky: years of 365, 365.25, 365.2425 or what days? These parameters also change with time.

clear Tide;

% w1 w2 w3 w4 w5 w6

Tide.Name{1} = 'M2'; Tide.Doodson{ 1} = [+2 0 0 0 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 1} = 'Principal lunar, semidiurnal';

Tide.Name{2} = 'S2'; Tide.Doodson{ 2} = [+2 +2 -2 0 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 2} = 'Principal solar, semidiurnal';

Tide.Name{3} = 'N2'; Tide.Doodson{ 3} = [+2 -1 0 +1 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 3} = 'Principal lunar elliptic, semidiurnal';

Tide.Name{4} = 'L2'; Tide.Doodson{ 4} = [+2 +1 0 -1 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 4} = 'Lunar semi-diurnal: with N2 for varying speed around the ellipse';

Tide.Name{5} = 'K2'; Tide.Doodson{ 5} = [+2 +2 -1 0 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 5} = 'Sun-Moon angle, semidiurnal';

Tide.Name{6} = 'K1'; Tide.Doodson{ 6} = [+1 +1 0 0 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 6} = 'Sun-Moon angle, diurnal';

Tide.Name{7} = 'O1'; Tide.Doodson{ 7} = [+1 -1 0 0 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 7} = 'Principal lunar declinational';

Tide.Name{8} = 'Sa'; Tide.Doodson{ 8} = [ 0 0 +1 0 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 8} = 'Solar, annual';

Tide.Name{9} = 'nu2'; Tide.Doodson{ 9} = [+2 -1 +2 -1 0 0]; Tide.Title{ 9} = 'Lunar evectional constituent: pear-shapedness due to the sun';

Tide.Name{10} = 'Mm'; Tide.Doodson{10} = [ 0 +1 0 -1 0 0]; Tide.Title{10} = 'Lunar evectional constituent: pear-shapedness due to the sun';

Tide.Name{11} = 'P1'; Tide.Doodson{11} = [+1 +1 -2 0 0 0]; Tide.Title{11} = 'Principal solar declination';

Tide.Constituents = 11;

% Because w0 + w3 = w1 + w2, the basis set {w0,...,w6} is not independent. Usage of w0 (or of EMS.T) can be eliminated.

% For further pleasure w2 - w6 correspond to other's usage of w1 - w5.

% Collect the basic angular speeds into an array as per A. T. Doodson's organisation. The classic Greek letter omega is represented as w.

clear w;

% w(0) = EMS.T + EMS.s - EMS.h; % This should be w(0), but MATLAB doesn't allow this!

w(1) = EMS.T;

w(2) = EMS.s;

w(3) = EMS.h;

w(4) = EMS.p;

w(5) = EMS.N;

w(6) = EMS.pp;

% Prepare the basis frequencies, of sums and differences. Doodson's published coefficients typically have 5 added

% so that no negative signs will disrupt the layout: the scheme here does not have the offset.

disp('Name °/hour Hours Days');

for i = 1:Tide.Constituents

Tide.Speed(i) = sum(Tide.Doodson{i}.*w); % Sum terms such as DoodsonNumber(j)*w(j) for j = 1:6.

disp([int2str(i),' ',Tide.Name{i},' ',num2str(Tide.Speed(i)),' ',num2str(360/Tide.Speed(i)),' ',num2str(15/Tide.Speed(i)),' ',Tide.Title{i}]);

end;

clear Place;

% The amplitude H and phase for each constituent are determined from the tidal record by least-squares

% fitting to the observations of the amplitudes of the astronomical terms with expected frequencies and phases.

% The number of constituents needed for accurate prediction varies from place to place.

% In making up the tide tables for Long Island Sound, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

% uses 23 constituents. The eleven whose amplitude is greater than .1 foot are:

Place(1).Name = 'Bridgeport, Cn'; % Counting time in hours from midnight starting Sunday 1 September 1991.

% M2 S2 N2 L2 K2 K1 O1 Sa nu2 Mm P1...

Place(1).A = [ 3.185 0.538 0.696 0.277 0.144 0.295 0.212 0.192 0.159 0.108 0.102]; % Tidal heights (feet)

Place(1).P = [-127.24 -343.66 263.60 -4.72 -2.55 142.02 505.93 301.5 45.70 86.82 340.11]; % Phase (degrees).

% The values for these coefficients are taken from http://www.math.sunysb.edu/~tony/tides/harmonic.html

% which originally came from a table published by the US. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

% Calculate a tidal height curve, in terms of hours since the start time.

PlaceCount = 1;

Colour=cellstr(strvcat('g','r','b','c','m','y','k')); % A collection.

clear y;

step = 0.125; LastHour = 720; % 8760 hours in a year.

n = LastHour/step + 1;

y(1:n,1:PlaceCount) = 0;

t = (0:step:LastHour)/24;

for it = 1:PlaceCount

i = 0;

for h = 0:step:LastHour

i = i + 1;

y(i,it) = sum(Place(it).A.*cosd(Tide.Speed*h + Place(it).P)); %Sum terms A(j)*cos(speed(j)*h + p(j)) for j = 1:Tide.Constituents.

end; % Should use cos(ix) = 2*cos([i - 1]*x)*cos(x) - cos([i - 2]*x), but, for clarity...

end;

figure(1); clf; hold on; title('Tidal Height'); xlabel('Days');

for it = 1:PlaceCount

plot(t,y(1:n,it),Colour{it});

end;

legend(Place(1:PlaceCount).Name,'Location','NorthWest');

Results

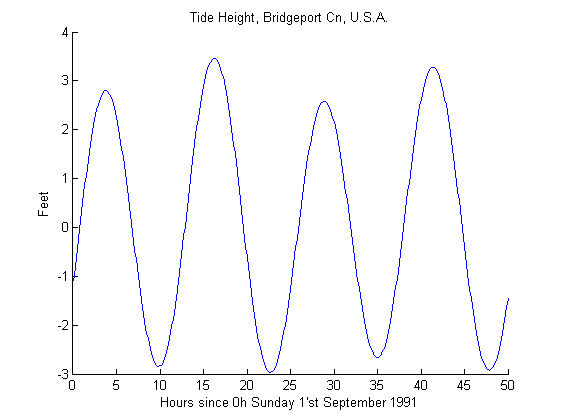

This shows the common pattern of two tidal peaks in a day, though remember that the repeat time is not exactly twelve hours but 12.4206 hours. The two peaks are not equal: the twin tidal bulges beneath the moon and on the far side of the earth are aligned with the moon. Bridgeport is north of the equator, so when the moon is north of the equator also and shining upon Bridgeport, Bridgeport is closer to its maximum effect than approximately twelve hours later when Bridgeport is on the far side of the earth from the moon and the high tide bulge at Bridgeport's longitude has its maximum south of the equator. Thus the two high tides a day alternate in maximum heights: lower high (just under three feet), higher high (just over three feet), and again. Likewise for the low tides.

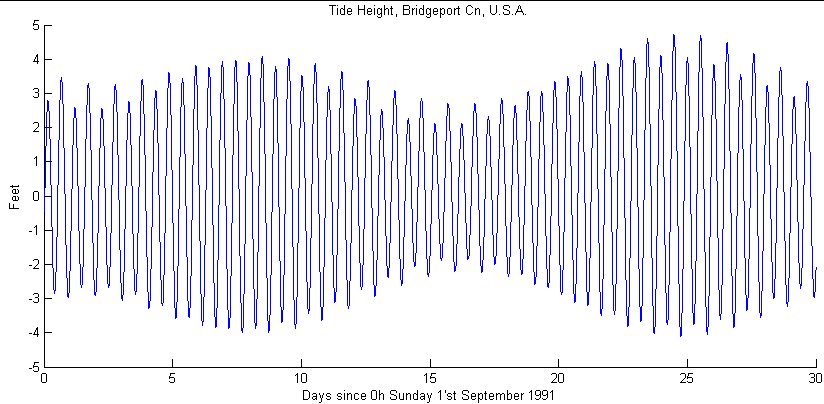

This shows the spring tide/ neap tide cycle in the amplitudes of the tides as the moon orbits the earth from being in line (Sun - Earth - Moon, or Sun - Moon - Earth) when the two main influences combine to give the spring tides, to when the two forces are opposing each other as when the angle Moon - Earth - Sun is close to ninety degrees producing the neap tides. Note also as the moon moves around its orbit it also changes from north of the equator to south of the equator. The alternation in the heights of the high tides becomes smaller, until they are the same (the moon is above the equator), then redevelops but with the other polarity, waxing to a maximum difference and then waning again.

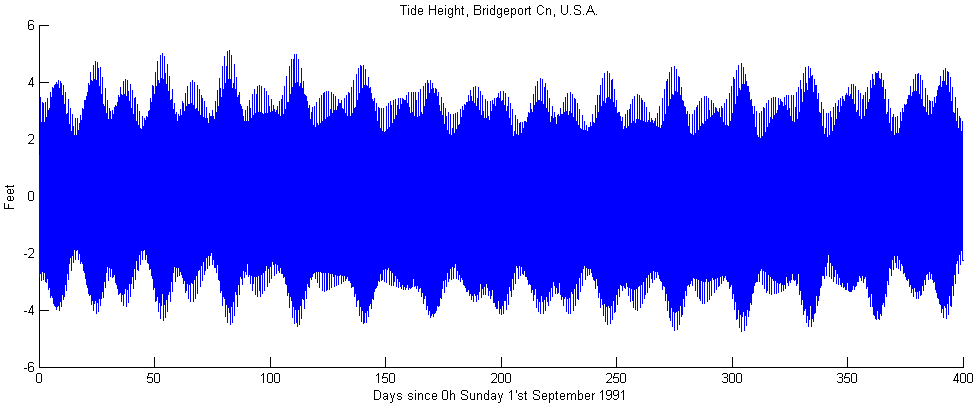

This shows just over a year's worth of tidal height calculations. The sun also cycles between being north or south of the equator and as well the Earth - Sun and Earth - Moon distances change on their own cycles. None of the various cycle periods are commensurate, and the pattern does not repeat.

Remember always that calculated tidal heights take no account of weather effects, nor include any changes to conditions since the coefficients were determined, such as movement of sandbanks or dredging, etc.

References

- ↑ Proudman, J. (1968). "Arthur Thomas Doodson 1890-1968". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 14: 189–126. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1968.0008.

- ↑ Carlsson-Hyslop, Anna (2015). "Human Computing Practices and Patronage: Antiaircraft Ballistics and Tidal Calculations in First World War Britain". Information & Culture: A Journal of History. 50 (1): 70–109. doi:10.1353/lac.2015.0004.

- ↑ Doodson, A. T. (1921). "The Harmonic Development of the Tide-Generating Potential". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 100 (704): 305. Bibcode:1921RSPSA.100..305D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1921.0088.

- ↑ S Casotto, F Biscani, "A fully analytical approach to the harmonic development of the tide-generating potential accounting for precession, nutation, and perturbations due to figure and planetary terms", AAS Division on Dynamical Astronomy, April 2004, vol.36(2), 67.

- 1 2 D E Cartwright, "Tides: a scientific history", Cambridge University Press 2001, at pages 163-4.

- ↑ See also the account of the Doodson-Légé TPM at the National Oceanography Centre.

- ↑ National Oceanography Centre website.

- ↑ Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory (history section); biography of Dr A T Doodson Archived 26 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ↑ http://royalsociety.org/DServe/dserve.exe?dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqDb=Catalog&dsqCmd=show.tcl&dsqSearch=(RefNo==%27EC%2F1933%2F05%27)

- ↑ 'D-Day Has Come', BBC

- ↑ Wirral History - Flaybrick Cemetery, www.wirralhistory.net, retrieved 15 January 2012

- ↑ "Doodson, Arthur Thomas". Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ↑ See e.g. T D Moyer (2003), "Formulation for observed and computed values of Deep Space Network data types for navigation", vol.3 in Deep-space communications and navigation series, Wiley (2003), e.g. at pp.126-8.

- 1 2 Melchior, P. (1971). "Precession-nutations and tidal potential". Celestial Mechanics. 4 (2): 190–212. Bibcode:1971CeMec...4..190M. doi:10.1007/BF01228823. and T D Moyer (2003) already cited.

- ↑ See for example Melchior (1971), already cited, at p.191.

External links

- Works by or about Arthur Thomas Doodson at Internet Archive

- doodson.m Matlab/Octave function of main tidal waves Doodson's arguments and period.