Ophiomyia simplex

| Ophiomyia simplex | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Family: | Agromyzidae |

| Genus: | Ophiomyia |

| Species: | O. simplex |

| Binomial name | |

| Ophiomyia simplex (Loew, 1869) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

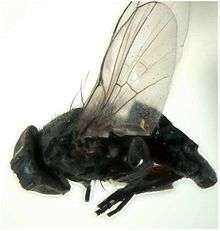

The asparagus miner (Ophiomyia simplex Loew; Diptera; Agromyzidae) is a specialist on asparagus (Asparagus officinalis L.) and is a problem for asparagus growers. It is shiny black and occurs in most major asparagus producing regions of the world.

Identification

The asparagus miner is a bivoltine stem-mining fly and a major pest of asparagus. It is small (~2–5 mm) with a shiny black body and black legs [1] Under a dissecting microscope or with a hand lens, one can confirm the identity of the fly by checking that the costa (the thicker marginal vein) ends at vein R4+5.[2] In addition, the fly has five conspicuous orbital bristles emerging from the middle of its head. The maggots (immature stages) may be up to 5 mm long, and can be found feeding internally in asparagus stems. They are creamy white in appearance, with the anterior spiracles on short stalks. The pupae are darker brown or reddish, and can sometimes be seen as dried skin from the stem peels back around parts that have been mined.

Distribution & History

The asparagus miner occurs in most major asparagus producing regions of the world. The fly was first described by Loew from Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York in the United States in 1869. However, because it is host-specific to asparagus, it was likely introduced to the United States from Europe when asparagus was brought over by settlers. It has been recorded from Germany,[3] Great Britain,[4] France,[5][6] Canada,[7] other locales in the United States,[8][9] and many other countries. The species was originally described as Agromyza simplex, was moved to Melangromyza simplex and its current species name after revisions is Ophiomyia simplex. Some authors, including Tschirnhaus have tried to move simplex to Hexomyza, but this has been met with skepticism by other authors.[10]

Fungal Vector

The miner is a possible passive vector of pathogenic species of fungi [11][12] that are responsible for the development of Fusarium crown and root rot and early decline of fields.[13] Species in this fungal complex include Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium proliferatum, among others,[14] and these can shave 5–8 years off the economic life span of an asparagus field. The fly may passively vector the fungi from spores injected into the asparagus plant from the ovipositor or the sites of mining damage may create entrance points for the fungal spores from windblown sand.[15]

Life Cycle

Adult asparagus miners emerge in mid-May in the northern United States,[16] and seek out recently planted asparagus fields that have gone to fern,[17] which may be especially vulnerable to infestation by the fly. First generation adults peak in abundance during mid-June.[18] After mating, females lay eggs at the base of asparagus stems at the soil surface level or just below.[16] Upon hatching, maggots undergo three larval instars or stages before pupating underneath the stem of the asparagus plant.[4] As they develop, the asparagus miner feeds on cortical tissue.[8]:8 After pupation, the second generation of adult asparagus miners peaks around mid-July to mid-August in the United States.[16] The end of adult flight happens in October and the asparagus miner overwinters as a pupa inside senesced asparagus stems.

Spatial Distribution

Research has shown that the asparagus miner is evenly distributed in an asparagus field during first generation flight, while during the second generation, the asparagus miner is predominately found along the edges of the field.[19] While in the first generation, growers may need to spray the entire asparagus field, during the second generation, growers may be able to treat the margins of asparagus fields and retain adequate control of asparagus miner populations. Neighboring habitat has been shown to influence the abundance of asparagus miner as well, with forested edges of fields resulting in decreases in abundance of the asparagus miner.[19] Moreover, asparagus fields bordered by other asparagus fields have elevated abundance of asparagus miners. As a result, it is often of practical value to conserve forested and natural border habitats around asparagus fields.

Management

An integrated pest management program should be established in problem fields that combine 1) monitoring using yellow sticky traps [20] or scouting, 2) use of degree-day model to guide decisions about spraying (Morrison, in press), and 3) enhancement of biological control from the natural enemies of the asparagus miner. The degree-day model can be accessed in the near future on Enviroweather’s website, a free service maintained by Michigan State University Extension and tied into a statewide network of weather stations. Research is currently ongoing in the investigation of which flowering resources benefit the natural enemies of the asparagus the most.[21] Currently, growers apply broad spectrum pesticides, most commonly Sevin, to treat for adult asparagus miners in the field. Coupling this management action with the degree-day model may allow growers to save money on chemicals and spare unneeded environmental costs.

More Information

More information can be found in the references to this article, or by going to the Vegetable Entomology website at Michigan State University to find more resources regarding insect pests in asparagus. This article was written with funding aid from the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant#2012-67011-19672 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture to Mr. W.R. Morrison at Michigan State University.

References

- ↑ Szendrei, Zsofia; W.R. Morrison III (2011). "Asparagus miner factsheet" (PDF). East Lansing, MI, USA: Michigan State University Extension, Department of Entomology. pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Spencer, KA (1973). Agromyzidae (Diptera) of Economic Importance. Germany: Springer.

- ↑ Dingler, M (1934). "Die kleine Spargelfliege". Anzeiger für Schädlingskunde (134-139).

- 1 2 Barnes, HF (1937). "The asparagus miner (Melanagromyza simplex) H. Loew)". Annals of Applied Biology. 24: 574–618. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1937.tb05854.x.

- ↑ Brunel, E; P Larue (1987). "La mineuse des tiges de l'asperge premiere appreciation de sa nuisibilite". Phytoma. 390: 42–44.

- ↑ Giard, A (1904). "Sur l'Agromyza simplex H. Loew parasite de l'asperge (Dipt).". Bulletin Société Entomologique de France: 176–178.

- ↑ Mailloux, G; V Vujanovic; C Hamel (2004). Identification rapide des insectes auxiliaires dans les aspergerais du Québec. Saint Bruno, Canada: Institut de Recherche et de Development en Agroenvironment.

- 1 2 Eichmann, RD (1943). "Asparagus miner not really a pest". Journal of Economic Entomology. 36: 849–852.

- ↑ Fink, DE (1913). "The asparagus miner and the twelve-spotted asparagus beetle". Vol 331, Bulletin of the Cornell Agricultural Experiment Station. Ithaca, NY, USA. pp. 411–421.

- ↑ Zlobin, VV (2005). "A new species of Melanagromyza feeding on giant hogweed in the Caucasus (Diptera: Agromyzidae)" (PDF). Zoosystematica Rossica. 14 (1): 173–177.

- ↑ 10

- ↑ Gilbertson, RL; WJ Manning; DN Ferro (1985). "Association of the asparagus miner with stem rot caused in asparagus by Fusarium species". Phytopathology. 75: 1188–1191. doi:10.1094/phyto-75-1188.

- ↑ Grogan, RG; KA Kimble (1959). "The association of Fusarium wilt and root rot with the asparagus decline and replant problem in California". Phytopathology. 49: 122–125.

- ↑ Gordon, TR; RD Martyn (1997). "The evolutionary biology of Fusarium oxysporum". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 35: 111–128. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.35.1.111.

- ↑ Morrison III, WR; JK Tuell; MK Hausbeck; Z Szendrei (2011). "Constraints on asparagus production: the association of Ophiomyia simplex (Diptera: Agromyzidae) and Fusarium spp." (PDF). Crop Science. 51: 1414–1423. doi:10.2135/cropsci2011.01.0032.

- 1 2 3 Ferro, DN; RL Gilbertson (1982). "Bionomics and population dynamics of the asparagus, Ophiomyia simplex (Loew), in Western Massachusetts". Environmental Entomology. 11: 639–644.

- ↑ Tuell, JK (2003). "Fusarium and the asparagus miner (Ophiomyia simplex) in Michigan". Department of Plant Pathology, Master of Science, Michigan State University. East Lansing, MI, USA.

- ↑ Tuell, JK; MK Hausbeck (2008). "Characterization of the Ophiomyia simplex (Diptera: Agromyzidae) activity in commercial asparagus fields and its association with Fusarium crown and root rot". 11th International Symposium on Asparagus, Acta Horticulturae: 203–210.

- 1 2 Morrison III, WR; Z Szendrei (2013). "Patterns of spatial and temporal distribution of the asparagus miner (Diptera: Agromyzidae): implications for management" (PDF). Journal of Economic Entomology. 106 (3): 1218–1225. doi:10.1603/ec13018.

- ↑ Ferro, DN; GJ Suchak (1980). "Assessment of visual traps for monitoring the asparagus miner, Ophiomyia simplex (Agromyzidae: Diptera)". Entomologia et Experimentalis Applicata. 28: 177–182. doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.1980.tb03002.x.

- ↑ Z Szendrei; WR Morrison III (2012). "The asparagus miner and its natural enemies in Michigan". Michigan State University Extension, Department of Entomology. East Lansing, MI, USA. pp. 1–2.