Barr body

A Barr body (named after discoverer Murray Barr)[1] is the inactive X chromosome in a female somatic cell,[2] rendered inactive in a process called lyonization, in those species in which sex is determined by the presence of the Y (including humans) or W chromosome rather than the diploidy of the X. The Lyon hypothesis states that in cells with multiple X chromosomes, all but one are inactivated during mammalian embryogenesis.[3] This happens early in embryonic development at random in mammals,[4] except in marsupials and in some extra-embryonic tissues of some placental mammals, in which the father's X chromosome is always deactivated.[5]

In humans with more than one X chromosome, the number of Barr bodies visible at interphase is always one fewer than the total number of X chromosomes. For example, men with Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY karyotype) have a single Barr body, whereas women with a 47,XXX karyotype have two Barr bodies. Barr bodies can be seen on the nucleus of neutrophils.

Mechanism

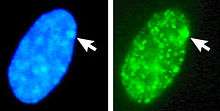

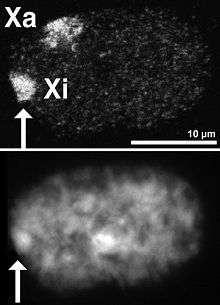

A typical human female has only one Barr body per somatic cell, while a typical human male has none.

Mammalian X-chromosome inactivation is initiated from the X inactivation centre or Xic, usually found near the centromere.[6] The center contains twelve genes, seven of which code for proteins, five for untranslated RNAs, of which only two are known to play an active role in the X inactivation process, Xist and Tsix.[6] The centre also appears to be important in chromosome counting: ensuring that random inactivation only takes place when two or more X-chromosomes are present. The provision of an extra artificial Xic in early embryogenesis can induce inactivation of the single X found in male cells.[6]

The roles of Xist and Tsix appear to be antagonistic. The loss of Tsix expression on the future inactive X chromosome results in an increase in levels of Xist around the Xic. Meanwhile, on the future active X Tsix levels are maintained; thus the levels of Xist remain low.[7] This shift allows Xist to begin coating the future inactive chromosome, spreading out from the Xic.[8] In non-random inactivation this choice appears to be fixed and current evidence suggests that the maternally inherited gene may be imprinted.[4]

It is thought that this constitutes the mechanism of choice, and allows downstream processes to establish the compact state of the Barr body. These changes include histone modifications, such as histone H3 methylation(i.e. H3K27me3 by PRC2 which is recruited by Xist)[9] and histone H2A ubiquitination,[10] as well as direct modification of the DNA itself, via the methylation of CpG sites.[11] These changes help inactivate gene expression on the inactive X-chromosome and to bring about its compaction to form the Barr body.

See also

References

Links to full text articles are provided where access is free, in other cases only the abstract has been linked.

- ↑ Barr, M. L., Bertram, E. G., (1949), A Morphological Distinction between Neurones of the Male and Female, and the Behaviour of the Nucleolar Satellite during Accelerated Nucleoprotein Synthesis. Nature. 163 (4148): 676-7.

- ↑ Lyon, M. F., (2003), The Lyon and the LINE hypothesis. j.semcdb 14, 313-318. (Abstract)

- ↑ Lyon, M. F. (1961), Gene Action in the X-chromosome of the Mouse (Mus musculus L.) Nature. 190 (4773): 372-3. doi:10.1038/190372a0 PMID 13764598 (Abstract)

- 1 2 Brown,C.J., Robinson,W.P., (1997), XIST Expression and X-Chromosome Inactivation in Human Preimplantation Embryos. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 5-8 (Full Text PDF)

- ↑ Lee, J. T., (2003), X-chromosome inactivation: a multi-disciplinary approach. j.semcdb 14, 311-312. (doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.025 Abstract)

- 1 2 3 Rougeulle, C., Avner, P. (2003), Controlling X-inactivation in mammals: what does the centre hold?. j.semcdb 14, 331-340. (Abstract)

- ↑ Lee, J. T., Davidow, L. S., Warshawsky, D., (1999), Tisx, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nat. Genet. 21, 400-404. Full Text

- ↑ Lyon, M. F., (2003), The Lyon and the LINE hypothesis. j.semcdb 14, 313-318. (Abstract

- ↑ Heard, E., Rougeulle, C., Arnaud, D., Avner, P., Allis, C. D. (2001), Methylation of Histone H3 at Lys-9 Is an Early Mark on the X Chromosome during X Inactivation. Cell 107, 727-738. (Full Text)

- ↑ de Napoles,M., Mermoud,J.E., Wakao,R., Tang,Y.A., Endoh,M., Appanah,R., Nesterova,T.B., Silva,J., Otte,A.P., Vidal,M., Koseki,H., Brockdorff,N., (2004), Polycomb Group Proteins Ring1A/B Link Ubiquitylation of Histone H2A to Heritable Gene Silencing and X Inactivation. Dev. Cell 7, 663-676 (Abstract)

- ↑ Chadwick,B.P., Willard,H.F., (2003), Barring gene expression after XIST: maintaining faculative heterochromatin on the inactive X. j.semcdb 14, 359-367 (Abstract)

Further reading

- Alberts,B., Johnson,A., Lewis,J., Raff,M., Roberts,K., Walter,P., (2002), Molecular Biology of the Cell, Fourth Edition, (428-429) Garland Science, 0-8153-4072-9 (Web Edition, Free access)

- Turnpenny & Ellard: Emery's Elements of Medical Genetics 13E (http://www.studentconsult.com/content/default.cfm?ISBN=9780702029172&ID=HC006029)