Artillery battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit of guns, mortars, rockets or missiles so grouped to facilitate better battlefield communication and command and control, as well as to provide dispersion for its constituent gunnery crews and their systems. The term is also used in a naval context to describe groups of guns on warships.

Land usage

Historically the term "battery" referred to a cluster of cannon in action as a group, either in a temporary field position during a battle or at the siege of a fortress or a city. Such batteries could be a mixture of cannon, howitzer, or mortar types. A siege could involve many batteries at different sites around the besieged place. The term also came to be used for a group of cannon in a fixed fortification, for coastal or frontier defence. During the 18th century "battery" began to be used as an organizational term for a permanent unit of artillery in peace and war, although horse artillery sometimes used "troop" and fixed position artillery "company". They were usually organised with between six and 12 ordnance pieces, often including cannon and howitzers. By the late 19th century "battery" had become standard mostly replacing company or troop.

In the 20th century the term was generally used for the company level sub-unit of an artillery branch including field, air-defence, anti-tank and position (coastal and frontier defences). Artillery operated target acquisition emerged during the First World War and were also grouped into batteries and have subsequently expanded to include the complete intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance (ISTAR) spectrum. 20th-century firing batteries have been equipped with mortars, guns, howitzers, rockets and missiles.

Mobile batteries

During the Napoleonic Wars some armies started grouping their batteries into larger administrative and field units. Groups of batteries combined for field combat employment called Grand Batteries by Napoleon.

Administratively batteries were usually grouped in battalions, regiments or squadrons and these developed into tactical organisations. These were further grouped into regiments, simply "group" or brigades, that may be wholly composed of artillery units or combined arms in composition. To further concentrate fire of individual batteries, from World War I they were grouped into "artillery divisions" in a few armies. Coastal artillery sometimes had completely different organizational terms based on shore defence sector areas.

Batteries also have sub-divisions, which vary across armies and periods but often translate into the English "platoon" or "troop" with individual ordnance systems called a "section" or "sub-section", where a section comprises two artillery pieces.

The rank of a battery commander has also varied, but is usually a lieutenant, captain, or major.

The number of guns, howitzers, mortars or launchers in an organizational battery has also varied, with the calibre of guns usually being an important consideration. In the 19th century four to 12 guns was usual as the optimum number to maneuver into the gun line. By late 19th century the mountain artillery battery was divided into a gun line and an ammunition line. The gun line consisted of six guns (five mules to a gun) and 12 ammunition mules.[1]

During the American Civil War, artillery batteries often consisted of six field pieces for the Union Army and four for the Confederate States Army, although this varied. Batteries were divided into sections of two guns apiece, each section normally under the command of a lieutenant. The full battery was typically commanded by a captain. Often, particularly as the war progressed, individual batteries were grouped into battalions under a major or colonel of artillery.

In the 20th century it varied between four and 12 for field artillery (even 16 if mortars), or even two pieces for very heavy pieces. Other types of artillery such as anti-tank or anti-aircraft have sometimes been larger. Some batteries have been "dual-equipped" with two different types of gun or mortar, and taking whichever was more appropriate when they deployed for operations.

From the late 19th century field artillery batteries started to become more complex organisations. First they needed the capability to carry adequate ammunition, typically each gun could only carry about 40 rounds in its limber so additional wagons were added to the battery, typically about two per gun. The introduction on indirect fire in the early 20th century necessitated two other groups, firstly observers who deployed some distance forward of the gun line, secondly a small staff on the gun position to undertake the calculations to convert the orders from the observers into data that could be set on the gun sights. This in turn led to the need for signalers, which further increased as the need to concentrate the fire of dispersed batteries emerged and the introduction fire control staff at artillery headquarters above the batteries.

Fixed battery

_Gun_on_Moncrieff_disappearing_mount%2C_at_Scaur_Hill_Fort%2C_Bermuda.jpg)

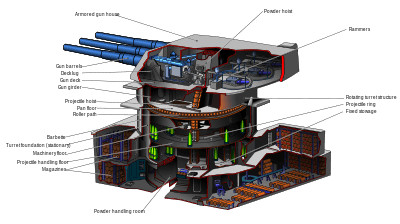

Fixed artillery refers to guns or howitzers on mounts that were either anchored in one spot (though capable of being moved for purposes of traverse and elevation), or on carriages intended to be moved only for the purposes of aiming, and not for tactical repositioning. Historical versions often closely resembled naval cannon of their day, "garrison carriages," like naval carriages, were short, heavy, and had four small wheels meant for rolling on relatively smooth, hard surfaces. Later, both naval and garrison carriages evolved traversing platforms and pivoting mounts. Such mounts were typically used in forts, or permanent defensive batteries, such as coastal artillery. Fixed batteries could be equipped with much larger guns than field artillery units could transport, and the gun emplacement was only one part of an extensive installation that included magazines and systems to deliver ammunition from the magazines to the guns. Improvements in mobile artillery, naval and ground; air attack; and precision guided weapons have limited fixed position's usefulness.

Naval usage

The term "battery" has also been used in association with warships. Early warships that mounted guns, such as the ship of the line, mounted dozens of cannons, carronades, and other guns in broadsides, sometimes on several decks. This remained the standard layout for centuries, until new designs, such as the revolving turret, made it obsolete.

The first operational use of a rotating turrets was on the American ironclad USS Monitor, designed by John Ericsson. Other designs used open barbettes to house their main batteries on rotating mounts. Both designs allowed naval engineers to dramatically reduce the number of guns present in the battery, by giving a handful of guns the ability to concentrate on either side of the ship.

A revolution in ship armament occurred in 1906, with the completion of HMS Dreadnought. In previous battleship designs, the main battery often consisted of four large caliber guns in two turrets: one forward and the other aft. The ships also had a mixed secondary battery of smaller guns that were also intended to be used offensively. The differences in gun calibers and ranges made it difficult to accurately judge shell splashes, and thus to fire the guns accurately, which led to decreased effectiveness of the ships. Dreadnought's design did away with the offensive secondary battery, and replaced it with a main battery of ten heavy caliber guns, and a smaller secondary battery to be used for self-defense. This leap in armament made all other battleships obsolete.

Often, ships have had a main battery for offensive purposes, and a secondary and sometimes even a tertiary (or more) battery for self-defense. An example of this was the German battleship Bismarck, which carried a main battery of eight 380 mm (15 in) guns, a secondary battery of twelve 150 mm (5.9 in) guns for defense against destroyers and torpedo boats, as well as a tertiary battery of various anti-aircraft guns ranging in caliber from 105-to-20 mm (4.13-to-0.79 in). Many later ships used dual-purpose guns to combine the functions of the secondary battery and the heavier guns of the tertiary batteries, in order to simplify the design.

Most modern vessels have largely done away with conventional artillery, instead using cruise and guided missiles for most offensive and defensive purposes, respectively. Guns are retained for niche roles, such as the Phalanx CIWS, a multi-barrel rotary cannon used for point defense, the Mark 45 5-inch (130 mm), or the Otobreda 76 mm, which is used for close defense against surface combatants and shore bombardment.

Modern battery organization

In modern battery organization, the military unit typically has six to eight howitzers or six to nine rocket launchers and 100 to 200 personnel and is the equivalent of a company in terms of organisation level.

In the United States Army, generally a towed howitzer battery has six guns, where a self-propelled battery (such as an M 109 battery) contains eight. They are subdivided into:

- Field batteries, equipped with 105 mm howitzers or equivalent;

- Medium batteries, equipped with 155 mm howitzers or equivalent;

- Heavy batteries, which are equipped with guns of 203 mm or more calibre, but are now very rare; and

- Various more specialised types, such as anti-aircraft, missile, or Multiple Launch Rocket System batteries.

- Headquarters batteries, which themselves have no artillery pieces, but are rather the command and control organization for a group of firing batteries (for example, a regimental or battalion headquarters battery).

The battery is typically commanded by a captain in US forces and is equivalent to an infantry company. A US Army battery is divided into the following units:

- The firing section, which includes the individual gun sections. Each gun section is typically led by a staff sergeant (US Army Enlisted pay grade E-6); the firing section as a whole is usually led by a lieutenant and a senior NCO.

- The fire direction center (FDC), which computes firing solutions based on map coordinates, receives fire requests and feedback from observers and infantry units, and communicates directions to the firing section. It also receives commands from higher headquarters (i.e. the battalion FDC sends commands to the FDCs of all three of its batteries for the purpose of synchronizing a barrage).

Other armies can be significantly different, however. For example:

The United Kingdom and Commonwealth forces have classified batteries according to the caliber of the guns. Typically:

- Field or light batteries, equipped with 105 mm howitzers or smaller

- Medium batteries, equipped with larger calibres, up to155 mm howitzers or equivalent

- Heavy batteries, with larger calibres although until after WWII 155mm were classified as heavy

- Various more specialised types, such as anti-aircraft, missile, or Multiple Launch Rocket System batteries

Headquarters batteries, which themselves have no artillery pieces, but are rather the command and control organization for a group of firing batteries (for example, a regimental or battalion headquarters battery).

The basic field organization being the "gun group" and the "tactical group". The former being reconnaissance and survey, guns, command posts, logistic and equipment support elements, the latter being the battery commander and observation teams that deploy with the supported arm. In these armies the guns may be split into several fire units, which may deploy dispersed over an extended area or be concentrated into a single position. In some cases batteries have operationally deployed as six totally separate guns, although sections (pairs) are more usual.

A battery commander, or "BC" is a Major (like his infantry company commander counterpart). However, in these armies the battery commander leads the "tactical group" and is usually located with the headquarters of the infantry or armoured unit the battery is supporting. Increasingly these direct support battery commanders are responsible for the orchestration of all forms of fire support (mortars, attack helicopters, other aircraft and naval gunfire) as well as artillery. General support battery commanders are likely to be at brigade or higher headquarters.

The gun group is commanded by the Battery Captain (BK), the battery's second-in-command. However this position has no technical responsibilities, its primary concern is administration, including ammunition supply, local defence and is based in the "wagon-lines" a short distance from the actual gun position, where the gun towing and logistic vehicles are concealed. Technical control is by the Gun Position Officer (GPO, a lieutenant) who is also the reconnaissance officer. The battery has two Command Posts (CP), one active and one alternate, the latter provides back-up in the event of casualties, but primarily moves with the preparation party to the next gun position and becomes the main CP there. Each CP is controlled by a Command Post Officer (CPO) who is usually a Lieutenant, 2nd Lieutenant or Warrant Officer Class 2. Gun positions may be "tight", perhaps 150 × 150 metres when the counter battery threat is low, or gun manoeuver areas, where pairs of self-propelled guns move around a far larger area, if the counter-battery threat is high.

During the Cold War NATO batteries that were dedicated to a nuclear role generally operated as "sections" comprising a single gun or launcher.

Groupings of mortars, when they are not operated by artillery, are usually referred to as platoons.

United States Marine Corps

155mm Howitzer Battery, Artillery Battalion, Artillery Regiment, Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force

(Battery Organization consisting of 147 Marines and Navy personnel, per Table of Organization T/O 1113G)

- Battery Headquarters

- Headquarters Section – Battery CO (Capt), Battery 1stSgt, plus 3 Marines

- Communications Section –16 Marines, led by the Radio Chief (SSGT)

- Maintenance Section – 11 Marines, led by the Battery Motor Transport Chief (GySgt)

- Medical Section – 3 Navy Hospital Corpsmen

- Liaison Section – led by the Liaison Officer (1stLt)

- Liaison Team – 5 Marines, led by the Observer Liaison Chief (SGT)

- Forward Observer Team (3) – 4 Marines, led by a Forward Observer (2ndLT)

- Firing Platoon

- Ammunition Section – 17 Marines, led by the Ammunition Chief (SSGT)

- Headquarters Section – Platoon Commander/Battery XO (1stLt), Battery Gunnery Sergeant (GySgt), and Local Security Chief/Platoon Sergeant (SSGT)

- Battery Operations Center – 5 Marines, led by the Assistant XO/FDO (2ndLt) and an Operations Assistant (SGT)

- Fire Direction Center – 9 Marines, led by the Fire Direction Officer (FDO) (1stLT) and the Operations Chief (SSGT)

- Artillery Section (6) – 10 Marines, led by the Section Chief (SSGT), with a Gunner (SGT), two Assistant Gunners (CPL), five Cannoneers (PVT-LCPL), and a Motor Vehicle Operator (LCPL) to operate and maintain the prime mover (i.e., truck used to tow the artillery piece and transport the gun crew and baggage).

Other armies can be significantly different, however. For example: the basic field organization being the "gun group" and the "tactical group". The former being reconnaissance and survey, guns, command posts, logistic, and equipment support elements, the latter being the battery commander and observation teams that deploy with the supported arm. In these armies the guns may be split into several fire units, which may deploy dispersed over an extended area or be concentrated into a single position. It some cases batteries have operationally deployed as six totally separate guns, although sections (pairs) are more usual.

See also

Notes

- ↑ p.263, Bethell

References

- Bethell, Henry Arthur, 1911, Modern Artillery in the Field: A Description of the Artillery of the Field, London, Macmillan and Co Ltd