Battle of Pungdo

| Battle of Pungdo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Sino-Japanese War | |||||||

Ukiyoe by Kobayashi Kiyochika dated August 1894 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3 cruisers |

1 cruiser 2 gunboats 1 transport | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

1 gunboat sunk 1 transport sunk 1 gunboat captured 1,100 (killed & wounded) | ||||||

The Battle of Pungdo or Feng-tao (Japanese: Hoto-oki kaisen (豊島沖海戦)) was the first naval battle of the First Sino-Japanese War. It took place on 25 July 1894 off Asan, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea, between cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy of Meiji Japan and components of the Beiyang Fleet of the Empire of China.

Background

Both Qing China and Japan had been intervening in Korea against the Donghak Peasant Revolution. While China tried to maintain her suzerain relationship with Korea, Japan wanted to increase her sphere of influence. Both countries had already had troops in Korea as requested by different factions within the Korean government. Chinese troops from the Beiyang Army, stationed in Asan, south of Seoul, numbering 3,000 men in early July, could be effectively supplied only by sea through the Bay of Asan. This presented a situation very similar to the British position at the beginning of the Yorktown campaign during the American Revolution.

The Japanese plan was to blockade the entrance of the Bay of Asan, while her land forces moved overland to encircle the Beiyang Army detachment in Asan before reinforcements arrived by sea.

Some amongst the Chinese Beiyang Fleet command were aware of this dangerous situation and had advocated either the withdrawal of troops further north to Pyongyang (captain of cruiser Jiyuan, Fang Boqian, the ranking Chinese officer in the Battle of Pungdo, among them), or the sailing the entire Beiyang fleet to Inchon as a deterrent against Japanese intentions. However, the Qing leadership was split between Viceroy Li Hongzhang's basic instinct to protect his fleet from danger and the Guangxu Emperor's demand for a stronger stand. As a compromise, the detachment at Asan was to be reinforced for the time being under escort by ships already on station in Korean waters. Inaction paralyzed the Chinese command on the eve of war.

The battle

According to Chinese records, the Chinese ships, cruiser Jiyuan and gunboat Kwang-yi (広乙/广乙), in port in Asan since 23 July, left on the morning of 25 July and were on their way to rendezvous with the troopship Kowshing (高陞) and Tsao-kiang (操江) en route from Tianjin. At 7:45 am, near Pungdo, a small island (also known as "Feng Island" in Western sources [1] sitting next to the two navigable channels out of the Bay of Asan, in Korean territorial waters, the two Chinese ships were fired upon by three Japanese cruisers Akitsushima, Naniwa, and Yoshino. Chinese ships returned fire at 0752 hours.

According to Japanese records, at 0700 on 25 July, the Japanese cruisers Yoshino, Naniwa and Akitsushima, which had been patrolling in the Yellow Sea off of Asan, encountered the Chinese cruiser Jiyuan, and gunboat Kwang-yi. These vessels had steamed out of Asan in order to meet another Chinese gunboat, Tsao-kiang , which was convoying the transport Kowshing toward Asan. The two Chinese vessels did not return the salute of the Japanese ships as required under International Maritime Regulations, and when the Japanese turned to the southwest, the Chinese opened fire.

The battle occurred at close range, and Jiyuen took severe damage and began to lose steering control, but one of the German military advisors aboard, Hoffman, managed to jury-rig a tiller under fire, and the vessel was able to maneuver. The timely arrival of the gunboat Kwang-yi distracted Naniwa, and Yoshino and Jiyuen used the opportunity to break off the engagement and escaped. Kwang-yi was stranded on some rocks, and its gunpowder magazine exploded. Yoshino pursued Jiyuen, but for uncertain reasons was unable to catch the slower vessel. In the meantime Tsao-kiang and the transport Kowshing, which was flying a British civil ensign and conveying some 1,200 Beiyang Army and stores, had the unfortunate timing of appearing on the scene.

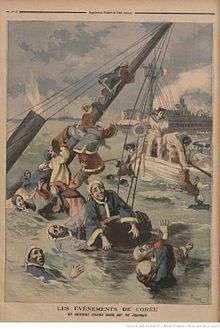

At approximately 0900 hours, Kowshing was ordered to follow the Japanese cruiser Naniwa to the main Japanese squadron. After a formal protest citing the neutrality of the British flag, the English captain, Thomas Ryder Galsworthy, agreed. However, the Chinese soldiers on board revolted, and threatened to kill the crew unless Galsworthy took them back to China. After four hours of negotiation, when the Beiyang troops were momentarily distracted, Galsworthy and the British crew jumped overboard and attempted to swim to Naniwa, but were fired upon by the Chinese. Most of the sailors were killed, but Galsworthy and two crewmen were rescued by the Japanese. Naniwa then opened fire on Kowshing, sinking her and her mutineers. A few on board (including German military advisor Major Constantin von Hanneken) escaped by swimming and was rescued by a local fisherman. The first officer of Kowshing gave an interview to The Times on 25 October 1894 stating that the Chinese were distracted by a torpedo launched from Naniwa, which failed to explode, and that he was only able to jump overboard after Naniwa started shelling Kowshing. While in the water, he was fired upon and wounded by the Chinese, but was rescued by the Japanese along with other European survivors. He also stated that Naniwa sunk two lifeboats full of Chinese troops. Only three out of the forty three crew of Kowshing survived the sinking.[2]

Chinese casualties were approximately 1,100, including more than 800 from the troop transport Kowshing alone, against none for the Japanese. Some 300 Chinese troops survived by swimming to nearby islands.

At 1400 hours, the cruiser Akitsushima intercepted Tsao-kiang which was quickly captured.

Aftermath of the battle

The battle had a direct impact on the fighting on land. The reinforcements with twelve cannons on board Kowshing and other military supplies on board Tsao-kiang failed to reach Asan. And the outnumbered and isolated Beiyang Army detachment in Asan was attacked and defeated in the subsequent Battle of Seonghwan four days later. Formal declarations of war came only on August 1, 1894, after the battle of Seonghwan.

Naniwa was under the command of Captain (later Fleet Admiral) Togo Heihachiro. The owners of Kowshing, Jardine, Matheson & Company (better known for its role in the opium trade with China, protested the action in the British press and demanded compensation from the Japanese government. The public response to Japan having fired upon a vessel flying the British flag almost led to a diplomatic incident between Japan and Great Britain. Japan also came under criticism for having failed to make any effort to rescue any of the Chinese survivors of the sinking. However, calls for Japan to pay an indemnity ceased after British jurists ruled that the action was in conformity with International Law regarding the treatment of mutineers.[1]

The sinking was also specifically cited by the Chinese government as one of the "treacherous actions" by the Japanese in their formal declaration of war against Japan.

One major result of this battle was the introduction of Western maritime prize rules into Japanese law. On 21 August 1894, a new Japanese law provided for the establishment of a Japanese prize court at Sasebo to judge on such matters.

In 2000, a Korean salvage company tried to salvage the wreck of Kowshing, claiming to investors that the ship contained a treasure of gold and silver bullion. The wreckage was destroyed in the operation, and only a few artifacts of little monetary value were discovered.[3]

Notes

- 1 2 Paine, S.C.M., Richard (2003). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perception, Power, and Primacy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81714-5.

- ↑ Sequence of events of sinking of Kowshing" and numbers of rescued and dead taken from several articles from The Times of London from 2 August 1894 – 25 October 1894

- ↑ Sino-Japanese War Research Society

References

- Chamberlin, William Henry. Japan Over Asia, 1937, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston, 395 pp.

- Elleman, Bruce A. (2001). Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795–1989. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21474-2.

- Evans, David (1979). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, MD: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Olender, Piotr (2014). Sino-Japanese Naval War 1894–1895. Sandomierz, Poland: Stratus s.c. ISBN 83-63678-30-9.

- Paine, S.C.M (2003). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-61745-6.

- Lone, Stewart. Japan's First Modern War: Army and Society in the Conflict with China, 1894–1895, 1994, St. Martin's Press, New York, 222 pp.

- Wright, Richard N. J.The Chinese Steam Navy 1862–1945 Chatham Publishing, London, 2000, ISBN 1-86176-144-9

External links

Coordinates: 37°05′48″N 126°34′58″E / 37.0968°N 126.5827°E