Battle of St. Jakob an der Birs

Coordinates: 47°32′31″N 7°37′05″E / 47.542°N 7.618°E

| Battle of St. Jakob an der Birs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Old Zürich War | |||||||

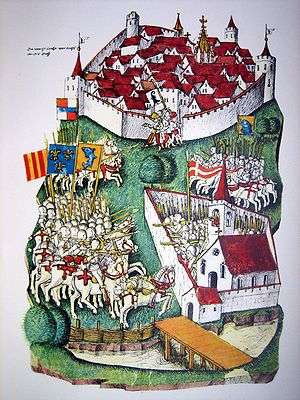

illustration of the battle in the Tschachtlanchronik of 1470. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000–40,000[1] | 1,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000[2] | 1200–1500[3] | ||||||

The Battle of St. Jakob an der Birs was fought between the Old Swiss Confederacy and French (mostly Armagnac) mercenaries, on the banks of the river Birs. The battle took place on 26 August 1444 and was part of the Old Zürich War. The site of the battle was near Münchenstein, Switzerland, just above 1 km outside the city walls of Basel, today within Basel's St-Alban district.

Background

In 1443, the seven cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy invaded the canton of Zürich and besieged the city. Zürich had made an alliance with Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, who now appealed to Charles VII of France to send an army to relieve the siege.

Charles, seeking to send away troublesome troops made idle by the truce with Henry VI of England in the Hundred Years' War, sent his son the Dauphin (later Louis XI of France) with an army of about 30,000 mercenaries into Switzerland, most of them Armagnacs, to relieve Zürich.[1] As the French forces entered Swiss territory at Basel, the Swiss commanders stationed at Farnsburg decided to send an advance troop of 1,300, mostly young pikemen. These moved to Liestal on the night of 25 August, where they were joined by a local force of 200.

The Battle

In the early morning, they managed to surprise and rout French vanguard troops at Pratteln and Muttenz. Enthused by this success, and in spite of strict orders to the contrary, the Swiss troops crossed the Birs to meet the bulk of the French army of some 30,000 men,[1] which was ready for battle.

Immediately the Swiss forces formed three pike squares of five hundred men each, and they fought well when Armagnac cavalry charged again and again and were repulsed.

Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (1405–1464, later Pope Pius II, until 1439 participant in the Council of Florence), described the battle in vivid detail, telling how the Swiss ripped bloody crossbow bolts from their bodies, and charged the enemy even after they had been pierced by spears or had lost their hands, charging the Armagnacs to avenge their [own] deaths.

The fighting lasted for several hours and was of an intensity evoking awed commentary from witnesses. Eventually, the Swiss pike squares weakened, so the commander ordered his men to retreat into a small hospital of St. Jakob. A reinforcement force from Basel was repulsed, and the Armagnac troops set their own artillery to bombarding the hospital. The Swiss pikemen suffered heavy casualties. The Swiss, as the offensive party, categorically refused to surrender and as the Armagnacs moved into the hospital, the remaining Swiss were pressed into the hospital's garden and killed to the last man within half an hour.

Aftermath

Even though the battle itself was a devastating defeat for the Swiss, and a major blow to Bern, the canton which contributed the force, it was nevertheless a Swiss success in strategic terms. In view of the heavy casualties on the French side, the original plan of moving towards Zürich, where a Swiss force of 30,000 was ready, was now judged unfavourably by the Dauphin and the French troops turned back, contributing to the eventual Swiss victory in the Old Zürich War. The actions of the Swiss was praised as heroic by contemporary observers and reports of the event quickly spread throughout Europe.

The Dauphin formally made peace with the Swiss Confederacy and with Basel in a treaty signed at Ensisheim on 28 October, and withdrew his troops from the Alsace in the spring of 1445. The intervention of the Church Council being held in the city of Basel at that time was crucial in instigating this peace: the Swiss Confederates were allies of the city of Basel, and so the Dauphin's war could also be construed as an aggressive act against the Council housed within its walls. Charles VII of France had implemented the reformist decrees of the Council of Basel in 1438, so it was important for the Dauphin not to appear to be threatening its members.[4]

In terms of military tactics, the battle exposed the weakness of pike formations against artillery, marking the beginning of the era of gunpowder warfare.

Legacy in Swiss historiography and patriotism

While the sheer bravery or foolhardiness on the Swiss side was recognized by contemporaries, it was only in the 19th century, after the collapse of the Napoleonic Helvetic Republic, that the battle came to be stylized as a kind of Swiss Thermopyle, a heroic and selfless rescue of the fatherland from a French invasion.[5]

The battle became a symbol of Swiss military bravery in the face of overwhelming odds and was celebrated in 19th century Swiss patriotism, finding explicit mention in Rufst du, mein Vaterland, the Swiss national anthem from the 1850s to 1961. A first monument at the site of the battle was erected in 1824, the current monument by Ferdinand Schlöth dates to 1872. Memorial ceremonies at the site were held from 1824, from 1860 to 1894 on a yearly basis, and afterwards every five years (discontinued after 1994).

The death of knight Burkhard VII. Münch, according to the chroniclers at the hands of a dying Swiss fighter, became symbolic of the outcome of the battle and the strategy of deterring powers of superior military strength from invading Switzerland by the threat of inflicting disproportionate casualties even in defeat, pursued by Swiss high command during the World Wars.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 the estimate of 30,000 to 40,000 troops is due to Hans Rudolf Kurz, Schweizerschlachten 2nd ed.

- ↑ ca. 2,000 dead on the Armagnac side according to Meyer (2012)

- ↑ reportedly all except for 16 who escaped; Meyer (2012) cites "about 1,200" dead on the Swiss side.

- ↑ Hardy, Duncan (2012). "The 1444-5 Expedition of the Dauphin Louis to the Upper Rhine in Geopolitical Perspective". Journal of Medieval History. 38 (3): 358–387. doi:10.1080/03044181.2012.697051.

- ↑ Wie einst der Spartanerkönig Leonidas und seine Schar hatte sich die tapfere Jungmannschaft der Eidgenossen geopfert, um das Vaterland vor der Zerstörung zu bewahren.' Volker Reinhardt, Die Geschichte der Schweiz. Von den Anfängen bis heute. C. H. Beck, München 2011.

- Werner Meyer: Battle of St. Jakob an der Birs in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2012.

- Miller, Douglas & Embleton G.A. The Swiss at War 1300-1500. London: Osprey Publishing, 1981. ISBN 0-85045-334-8

- Peter Keller, "Vom Siegen ermüdet", Weltwoche 16/2012.