Benjamin Ingham

| Benjamin Ingham | |

|---|---|

|

Benjamin Ingham | |

| Born |

1712 Ossett, Yorkshire |

| Died | 1772 |

| Residence | Aberford |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Batley Grammar School and Queen’s College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Cleric |

| Known for | Founding the Inghamites |

| Religion | Anglican, Methodist, Sandemanian, Independent |

| Spouse(s) | Lady Margaret |

| Children | Ignatius |

Benjamin Ingham (11 June 1712 [O.S.] - 1772), was born and raised in the Yorkshire and Humber region of England. He earned his B.A. degree from Oxford, and was ordained at age 23. Methodist connections from Oxford led to a colonial mission in America where he developed a keen interest in the Moravian church from German missionaries. Following a 1738 visit to Germany for greater exposure to the Moravian faith, Ingham returned to preaching in Yorkshire for the next four years. During this time he built up a following of more societies than he could manage. Ingham relinquished control of his societies to the Moravian Brethren in 1742. Ingham’s Moravian transformation occurred the year following his marriage to Lady Margaret Hastings. The Moravians, or Unitas Fratrum, were recognized by the British Crown in 1749 thereby creating the Moravian Church in England. While Ingham’s bond with his Brethren strengthened, it was a relationship that was to evolve. By the early 1750s Ingham found his views differing from the Oxford Methodists. When the viewpoints of the Moravian elders clashed with those representing the Church of England, Ingham used this 1753 scandal to distance himself from his Brethren and reestablish his own Inghamite societies. Still insecure as an independent church, Ingham turned to Sandemanianism during the final years of his life as a viable option forward for his followers. While he shared many Sandemanian views he chose independence instead. The majority of his societies splintered and joined with other denominations which included Methodists, Sandemanians and Congregationalists. He died at Aberford in 1772, four years after his wife.

Early life

Benjamin Ingham was born in Ossett, Yorkshire, on 11 June 1712 [O.S.]. His father, William Ingham, was a descendent of a group of clergy ejected from the Church of England by the Act of Uniformity 1662.[1] He attended Batley Grammar School and Queen’s College, Oxford, where he completed a B.A. degree in 1734. He was ordained the following year by the Bishop of Oxford, Dr. John Potter. While at Oxford, Ingham made the acquaintance of the Wesley brothers, John and Charles, and George Whitefield, all of whom had joined John Wesley’s society of Methodists at Oxford. This society has been referred to as the Holy Club.[2]

Missionary Work in Georgia

On 9 June 1732 [O.S.], King George II of Great Britain enacted a corporate charter authorizing James Oglethorpe to colonize the Province of Georgia. Oglethorpe planted his original colony near an Indian village along the banks of the Savannah River. The city that later formed here took on the name of the river that flowed past. Tomochichi, a Yamacraw chief, together with John and Mary Musgrove (outpost traders), were instrumental to Oglethorpe as mediators and interpreters in the establishment of peaceful relations between the original European settlers in Georgia and the Lower Creek people.

Word travelled quickly throughout Europe that both land and English citizenship were available in Georgia. Count Nicolous Ludwig von Zinzendorf arranged for August Gottlieb Spangenberg to lead a party of 10 Moravians to the province in January 1736, just ahead of Oglethorpe’s return. Scotch Highlanders sailed from Inverness aboard the Prince of Wales in October. They arrived in January 1736 and established their town of New Inverness. Rev. John McLeod was their minister.[3] After a four-month stay in England, Tomochichi's Creek party returned to Georgia with the first group of 56 Salzburgers.[4]

During his return to Georgia, Oglethorpe’s party of 231 persons set sail from Gravesend, Kent in December aboard the brigs Simond and London Merchant. They were accompanied on part of their journey by the sloop HMS Hawke. Among the passengers were the brothers, John and Charles Wesley, Benjamin Ingham, Chas. Delamotte, 26 Moravians led by their bishop, David Nitschman, and a second group of Salzburgers headed by Baron Philip George Friederich von Reck.[5] There were many other nationalities represented in this group of immigrants. These colonists arrived off Savannah on 8 February 1736 [O.S.].[6][7][8]

During the first months ashore, this second wave of colonists established fortifications and dwellings among and around the various settlements as they adjusted to their Georgian setting. The community leaders incessantly communicated with one another discussing future plans. The Moravian Brethren, at the inclination of Oglethorpe, built a schoolhouse near Tomochichi’s village to teach reading and writing to the Creek children. The site was named Irene, and was built over the grave of an earlier chief. John Töltschig led five other Moravians to the island location and started the construction on 13 August 1736 [N.S.].[9][10] The building had three rooms: one for Benjamin Ingham, one for Peter Rose and his wife, and the third would be the schoolroom for the children. The hut was finished the next month allowing the mission to proceed. This arrangement initially worked well for all parties. Benjamin Ingham acted as liaison between the main settlement in Savannah and this school, where he and the Roses instructed the children.

The Indian village went on the warpath, and Ingham sailed to England, via Pennsylvania on 9 March 1737 [N.S.]. He returned to London to rally support for the colony. In his possession were letters from Spangenberg to the Trustees of the Province of Georgia. John Wesley followed Ingham to London some months later.[11] Upon John Wesley’s return, the two journeyed with John Töltschig to Marienborn, home of Zinzendorf, and Herrnhut for greater exposure to Moravian Christianity.[12][13] John Wesley was replaced by George Whitefield as Oglethorpe’s Chaplain to Georgia.[14]

Fetter Lane, The London Influence

James Hutton was a London bookseller who made the acquaintance of the Wesley brothers during their Oxford schooling. While sending John Wesley off on his Georgian mission, Hutton was transformed by the experience he had on board Simond with the Moravian Brethren. Hutton recorded the date in his memoirs as Tuesday, 14 October 1735[O.S.].[15] So moved was he by this experience with them that he formed a society which met weekly in his home to pray. They concluded each meeting with a reading of the latest Wesley correspondence describing the ongoing mission with the Moravian Brethren. In this way they practiced until John Wesley’s return to England in 1738.

It was during this period that another young Moravian missionary, Peter Boehler, en route to America, was invited to one of these meetings at Fetter Lane. He had studied at the University of Jena and had been ordained by Count Zinzendorf. Peter’s inspiring presence transformed Hutton’s Society into “The Great Meeting House” which became the “First Religious Society in Fetter Lane, London.” This 1738 event could be described as planting the seed of the Moravian Church in England. This gathering, or “Vestry Society,” rightly considered themselves as part of the Church of England, and at times included members of the Holy Club. Peter Boehler established the rules he had learned under Zinzendorf, James Hutton presided, and Philip Henry Molther ministered. This society was repeatedly slandered for their “non-traditional” approach to Christianity. In response to the church doors being closed to their preaching, they shared the word in fields and on street corners to those who would listen.

The Fetter Lane Society continued to grow and looked to the Moravian connection for recognition of their achievement. Spangenberg returned to London in November 1742 to elevate the status of the society at Fetter Lane. He recognized the “First Religious Society in Fetter Lane, London” as a full congregation of Brethren and after introducing them to the rules and Officers of the German Congregation referred to them as the “London Church.” He saw this congregation as the union between the Moravian Church and the Church of England whose duty was to preach the Gospel.[16] Spangenberg's words were echoed by Zinzendorf to this London Church upon his return from America in March 1743.[17]

Return to Yorkshire, Preaching

Ingham returned to Yorkshire from his 1738 visit to Saxony where he reestablished his ministry in The North, primarily the countryside surrounding Wakefield, Leeds, and Halifax. The following summer the English clergy responded to the Methodists. Ingham, like his fellow ministers from Oxford, was forbidden to preach inside English churches, a condition that lasted some five years. These evangelists responded with open air preaching on street corners in London, and in the fields of Yorkshire to further the Gospel. Despite this opposition, Ingham strengthened his Moravian connection. Töltschig made his first visit to Yorkshire in 1739. Boehler followed in 1741 upon his return from America.[18] The Fetter Lane society served as the nerve center for Methodist communications throughout England. As Wesleys' theological views shifted away from those of the United Brethren, the chapel at 32 Fetter Lane was turned over to them.[19]

Marriage

Ingham made the lasting acquaintance of a Lady Margaret Hastings upon his return to Yorkshire. They were married on 12 November 1741 [O.S.]. Following this union, he relocated his residence to Aberford.[20] Beyond his personal life, Ingham cultivated tremendous growth from among his societies. He turned to Spangenberg, then residing in London, for help relinquishing personal control. Spangenberg immediately called for a pilgrimage. These settlers were organized along the lines of German communities in Herrnhut.[21][22] In addition to Spangenberg, the list of Moravians that answered this call to Yorkshire included Töltschig, Hutton and a great many others. This transfer of power strengthened the bond of trust between the Moravian Church and those English in communion with them on 30 July 1742 [O.S.].

Birth of a Settlement

Beyond Ingham’s societal reorganization, the Brethren needed land to farm. Zinzendorf’s 1743 visit to Yorkshire strengthened the fraternal bond with Ingham, who reciprocated to attend the Synog held in Vogtland later that year with his wife, Lady Margaret. The decision to purchase the property for the Fulneck pilgrim settlement was made at this Synog. Ingham purchased the Fallneck (or Fallen Oak) Estate in 1744 as a gift to the Brethren.[23] The foundation of Grace Hall, within the Fulneck settlement, was laid on 10 May 1746 with Br. Töltschig leading the congregation in the ceremony. This building was followed by the girls’ school in October 1749 and the boys’ school in 1753.[24] While the Fulneck settlement developed, the United Brethren Church continued to press for recognition from Great Britain in order to safeguard their missionaries from military service in the United Kingdom and overseas. Ingham, Hutton, and Bell aided this cause when they attained an audience with the King to demonstrate the loyalty of the United Brethren on 27 April 1744.[25] Parliament, with the firm backing of the Church of England, enacted legislation in 1749 championed by James Oglethorpe that recognized the “ancient Protestant Episcopal church” of these Moravian Brethren as being the same as their own.[26][27][28][29]

Detachment

By 1753 the leading Methodist personalities had distanced their theological views from those of the United Brethren. That same year, Count Zinzendorf’s Church suffered a credit crisis which severely strained what was left of those underlying friendships. This rift coincided with the end of Oglethorpe’s Charter to Georgia. Among the key issues during the transformation to a Crown colony were military service and slavery, both of which the Moravian Brethren opposed. Most of their settlements in Georgia had long since relocated to Pennsylvania. In response to this unfortunate situation, Ingham distanced himself and his societies from both the Moravian Church and the Church of England. He softened his initial demand for full payment of the land surrounding Grace Hall, to require only an annual rent for some 500 years.[30][31] His followers were referred to as Inghamites.[32] Ingham considered reunification for his societies with his associates from Oxford, the Wesley brothers, in 1755, but was unable to get John Wesley’s full support. Later that year in Lancashire, Ingham was elected to the position of “General Overseer” of his societies,[33] with James Allen and William Batty chosen as his two principal helpers.[34] By that time, Ingham had near 80 flourishing congregations that viewed him as their head Pastor.

In Search of

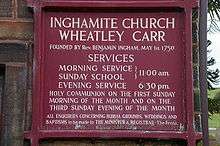

In 1759, Benjamin Ingham read Glas’s Testimony of the king of martyrs concerning his kingdom, and Sandeman's Letters on Theron and Aspasio.[35] Ingham, by way of correspondence with Glas and Sandeman, joined into discussion with them in an attempt to save his Inghamites through unification with congregations that most closely resembled those of the Moravian-Methodists he had established in Yorkshire. The following year, Ingham sent two of his ministers, James Allen and William Batty, on a discreet mission to Scotland to learn first-hand about Glasite practices. They formally reported to Ingham in October 1761. While their report swayed the conference decision from Methodism to Sandemanianism, they could not agree on the specifics of this transformation as Ingham intended to maintain his position as "General Overseer".[36] The resulting split left Batty supporting Ingham, neither of whom was willing to fully convert. The formal conversion would mean confessing their faith amongst a Sandemanian (or Glasite) congregation and being accepted as members of that community.[37][38] Allen returned to Scotland, converted, became an Elder, returned to Yorkshire as a missionary, and converted several Inghamite congregations to Sandemanianism.[39] Ingham’s congregations continued to act in an independent manner. They lacked the unifying organizational structure inherent in either the Moravian or the elder-led Sandemanian congregations. In the absence of such discipline, the Inghamite societies have slowly unraveled and have nearly been overtaken by Methodism, Sandemanianism, Congregationalism and others. In 1762, Ingham was elected an elder to the Church at Tadcaster, and continued in the office of "General Overseer" until his parting.[40] At the age of 60, Benjamin Ingham died in 1772, some four years after his wife, Lady Margaret, at Aberford. By 1863, the number of Inghamite chapels had been reduced to half a dozen. As of February 2010 there remain but two active Inghamite chapels located at Salterforth and Wheatley Lane.

Legacy

- His church.

- Benjamin Ingham wrote several hymns for inclusion with the Kendal Hymn Book published in Leeds in 1757 to which an appendix was added four years later.

- The 1886 edition of the Moravian Hymn book also contains two of Ingham’s works.[41]

- Ingham published A Discourse on the Faith and Hope of the Gospel in 1763 which explained his revised views on the Christian faith. This work was heavily influenced by the writings of John Glas and Robert Sandeman.[42]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benjamin Ingham. |

- ↑ See page 57 of Tyerman (1895).

- ↑ See page 60 of Tyerman (1895).

- ↑ See pages 62, 123-5, and 127 of Stevens (1847).

- ↑ See pages 146-150 of Bruce (1890).

- ↑ See page 131 of Stevens (1847). The Salzburgers were a group of Lutherans expelled around 1731 by the Catholic Ruler of Austria (see Early modern Europe).

- ↑ See page 767 Julian (1892).

- ↑ See pages 185, 186, and 245 of Spangenberg (1838).

- ↑ See pages 51-53 of Stevens (1878).

- ↑ See page 152 of Fries (1905). The German writer of this text wrote dates using only the Gregorian calendar.

- ↑ See page 365 of Stevens (1847).

- ↑ See pages 152-155, and 168 of Fries (1905).

- ↑ See "Inghamites" and "Moravians" in Canney (1921).

- ↑ See page 245 of Spangenberg (1838).

- ↑ See pages 16-23 of Smith (1877).

- ↑ See page 11 of Benham (1856).

- ↑ See page 186-88 of Hutton (1895).

- ↑ See pages 318 and 319 of Spangenberg (1838).

- ↑ See pages 244 - 246 of Seymour (1840).

- ↑ See pages 41, 228 and 229 of Benham (1856).

- ↑ See pages 121 and 127 of Tyerman (1873).

- ↑ See "Moravians" in Canney (1921).

- ↑ See pages 192 - 199 of Hutton (1895).

- ↑ See pages 111, 230, 234 and 268 of Benham (1856). This location was originally named Lamb’s Hill by Count Zinzendorf on one of his walks with Ingham.

- ↑ See pages 223 and 285 of Benham (1856). Among the listed workers was an Ignatius Ingham.

- ↑ See pages 3 and 150 of Benham (1856). Benham indicated this event was not recorded in the usual manner.

- ↑ See pages 211 and 212 of Hutton (1895). While portions of this Act were subsequently repealed in 1867 (United States achieved independence in 1783), the recognition of the Brethren Church would remain intact. The Royal Assent was provided the following month. The vast support for this Act by both the House of Lords and Church of England indicate the positive press the Moravians garnered for all of their tireless efforts dating back to the 1732 Georgia mission.

- ↑ See pages 388-390 of Spangenberg (1835).

- ↑ See pages 193 and 194 of Cooper (1904).

- ↑ See page 542 of The Statutes: Revised Edition, Vol. II. (1871).

- ↑ See pages 100, 123, and 124 of Tyerman (1873).

- ↑ See page 280 of Benham (1856).

- ↑ See page 198 of Fries (1905).

- ↑ See page 138 of Tyerman (1873).

- ↑ See "Moravians" in Canney (1921).

- ↑ See pages 55-6 of Cantor (1991).

- ↑ See page 145 of Tyerman (1873).

- ↑ See pages 43, 44, and 47 of Cantor (1991).

- ↑ See page 83 of Smith (2008).

- ↑ See pages 84-5 of Smith (2008). Through visitation by their elders, Sandemanians maintained an even handed discipline.

- ↑ See page 152 of Tyerman (1873).

- ↑ See "Inghamite Hymnology" and pages 1387 and 1467 of Julian (1892). Julian indicates Allen edited the 1748 Hymn book.

- ↑ See pages 147-151 of Tyerman (1873).

Bibliography

- Benham, Daniel: Memoirs of James Hutton: Comprising the Annuls of his Life and Connection with the United Brethren. (London, 1856).

- Bruce, Henry: The Life of General Oglethorpe, (London, 1890).

- Canney, Maurice A: An Encyclopedia of Religions, Routledge and Sons Ltd., (London, 1921).

- Cantor, Geoffrey N: Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist: A Study of Science and Religion in the Nineteenth Century, Macmillan (Hampshire, 1991).

- Cooper, Harriet C: James Oglethorpe, Founder of Georgia, (New York, 1904).

- Fries, Adelaide L: The Moravians in Georgia, 1735–1740, Edwards and Broughton (Raleigh, NC, 1905).

- Hutton, Joseph Edmund: A Short History of the Moravian Church, Moravian Publication Office (London, 1895).

- Julian, John Ed: A Dictionary of Hymnology, Charles Scribner’s Sons (New York, 1892).

- Seymour, Aaron C.H: The Life and Times of Selina Countess of Huntingdon, Painter, (London, 1840).

- Smith, Geo. G. Jr: The History of Methodism in Georgia and Florida from 1785–1865, (Macon, Ga.,1877).

- Smith, John Howard: The Perfect Rule of the Christian Religion: A History of Sandemanianism in the Eighteenth Century, SUNY (Albany, NY, 2008).

- Spangenberg, Rev. August Gottlieb: The life of Nicholas Lewis, Count Zinzendorf, bishop and ordinary of the United (or Moravian) Brethren, Original text published in 1772-1775. This translation by Samuel Jackson (London, 1838).

- Stevens, Abel: The History of the Religious Movement of the Eighteenth Century called Methodism. (London, 1878).

- Stevens, Rev. William Bacon: A History of Georgia From its First Discovery by Europeans to the Adoption of the Present Constitution in 1798. Vol. I. (New York, 1847).

- Thompson, Richard Walker: Benjamin Ingham (The Yorkshire Evangelist) and The Inghamites, R.W. Thompson & Co (Kendal, 1958)

- Tyerman, Luke: The Oxford Methodist: Memoirs of the Rev. Messrs. Clayton, Ingham, Gambold, Hervey, and Broughton, with Biographical Notices of Others, Harper and Brothers (New York, 1873).

- Great Britain: The Statutes: Revised Edition. Vol. II. William and Mary to 10 George III. A.D. 1688-1770. (London, 1871). 22nd Year of George II chapter XXX.

"Ingham, Benjamin". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Ingham, Benjamin". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.