Bennett Island

| Native name: <span class="nickname" ">Остров Бе́ннетта | |

|---|---|

A headland in Bennett Island. | |

|

Bennett Island is the westernmost island of the De Long group. | |

| Geography | |

| Location | East Siberian Sea |

| Coordinates | 76°44′N 149°30′E / 76.733°N 149.500°ECoordinates: 76°44′N 149°30′E / 76.733°N 149.500°E |

| Archipelago | De Long Islands |

| Total islands | 5 |

| Area | 150 km2 (58 sq mi) |

| Length | 29 km (18 mi) |

| Width | 14 km (8.7 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 426 m (1,398 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount De Long |

| Administration | |

|

Russia | |

| Federal subject | Far Eastern Federal District |

| Republic | Sakha |

| Demographics | |

| Population | uninhabited |

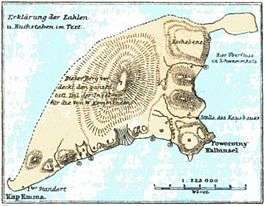

Bennett Island (Russian: Остров Бе́ннетта, Ostrov Bennetta) is the largest of the islands of the De Long group in the northern part of the East Siberian Sea. The area of this island is approximately 150 square kilometres (58 square miles) and it has a tombolo at its eastern end. The highest point of the island is 426 metres (1,398 feet) high Mount De Long, the highest point of the archipelago.

Bennett Island is part of the Sakha Republic administrative division of Russia.

History

Bennett Island was discovered by American explorer George Washington DeLong in 1881 and named after James Gordon Bennett, Jr., who had financed the expedition. DeLong set out in 1879 aboard the Jeannette, hoping to reach Wrangel Island and to discover open seas in the Arctic Ocean near the North Pole. However, the ship entered an ice pack near Herald Island in September 1879 and became trapped. The vessel was crushed by the ice and sank in June 1881. At that point the party was forced to trek over the ice on foot, discovering Bennett Island during July 1881, and claiming it for the United States. They remained on the island for several days before setting out again for the New Siberian Islands and the mainland of Siberia.[1][2]

In August 1901 Russian ship Zarya sailed on an expedition searching for the legendary Sannikov Land (Zemlya Sannikova) but was soon blocked by floating pack ice. During 1902 the attempts to reach Sannikov Land continued while Zarya was trapped in fast ice. Russian explorer Baron Eduard Toll and three companions vanished forever in November 1902 while travelling away from Bennett Island towards the south on loose ice floes.[3]

In 1916 the Russian ambassador in London issued an official notice to the effect that the Imperial government considered Bennett, along with other Arctic islands, integral parts of the Russian Empire. This territorial claim was later maintained by the Soviet Union.

Some U.S. individuals assert American ownership of Bennett Island, and others of the De Long group, based on the 1881 landing. However, the United States government has never claimed Bennett Island, and recognizes it as Russian territory.[4]

Geology

Bennett Island consists of Early Paleozoic, late Cretaceous, Pliocene, and Quaternary sedimentary and igneous rocks. The oldest rocks outcropping on Bennett island are moderately tilted marine Cambrian to Ordovician sedimentary rocks. They consist of an approximately 500-meter-thick sequence of argillites with minor amounts of siltstone, and limestone that contain Middle Cambrian trilobites and 1000–1200 m of Ordovician argillites, siltstones, and quartz sandstones that contain graptolites. These Paleozoic rocks are overlain by Late Cretacecous coal-bearing argillites and quartzite-like sandstones and basaltic lava and tuff with lenses of tuffaceous argillite. The Late Cretaceous strata is overlain by basaltic lavas ranging in age from Pliocene to Quaternary. The Quaternary volcanic rocks form volcanic cones.[5][6][7]

Climate

Little has been published about the climatology of Bennett Island in the English language literature. Dr. Glazovskiy[8] stated that the annual precipitation on Bennett Island varied from 100 mm at sea level to 400 mm at the crest of the Tollya Ice Cap.

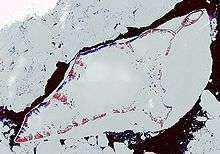

Glaciers

Bennett Island has the largest permanent ice cover within the De Long Islands. In 1987, the permanent ice cap of this island consisted of four separate glaciers that had a total area of 65.87 km² (25.43 mi²). All of these glaciers were perched on high, basaltic plateaus bounded by steep scarp-like slopes.[9]

In 1992, Dr. Verkulich and others[9] named these glaciers as the De Long East, De Long West, Malyy, and Toll glaciers. With an area of 55.5 km² (21.4 mi²) in 1987, Toll Glacier was the largest of them. It occupied the center of Bennett Island; had an elevation of 380 to 390 m (1,250 to 1,280 ft) above mean sea level; and was 160 to 170 m (524 to 560 ft) thick at its center. It had an outlet glacier, West Seeberg Glacier, from which ice flowed downhill from Toll Glacier into the sea. The next largest glacier was De Long East Glacier with an area of 5.16 km² (1.99 mi²) in 1987. It laid about 420 m (1,380 ft) above mean sea level at the southeast end of Bennett Island and had a thickness of 40 to 45 m (130 to 147 ft). Adjacent to De Long East Glacier laid the De Long West Glacier with an area of 1.17 km² (0.45 mi²); an elevation of 330 to 340 m (1,080 to 1,115 ft) above mean sea level; and a thickness of 40 m (130 ft) in 1987. Malyy Glacier, with an area of 4.04 km² (1.56 mi²) in 1987, occupied a basaltic plateau at an elevation of 140 to 160 m (460 to 525 ft) above mean sea level on the northeast end of Bennett Island and was 40 to 50 m (130 to 164 ft) thick. In 1987, all of these glaciers were shrinking in volume and had been so for the past 40 years.[9]

Of the glaciers described by Dr. Verkulich and others,[9] Dr. Glazovskiy[8] discusses only the Toll Ice Cap, which Dr. Verkulich and others[9] referred to as "Toll Glacier". In 1996, it had an area of 54.2 km² and a mean elevation of 384 m (1,260 ft) above sea level. Its equilibrium line altitude was at an elevation of 200 m (660 ft) above sea level.[8]

According to Alekseev,[10] Anisimov and Tumskoy,[11] and Makeyev and others,[12] the glaciers found on Bennett and other islands of the De Long Islands are remnants of small passive ice caps formed during the Last Glacial Maximum (Late Weichselian Epoch) about 17,000 to 24,000 BP. At the time that these ice caps formed, the De Long Islands were major hills within a large subaerial plain, called the Great Arctic Plain, that now lies submerged below the Arctic Ocean and East Siberian Sea.[13]

Vegetation

Rush/grass, forb, cryptogam tundra covers the Bennett Island. It is tundra consisting mostly of very low-growing grasses, rushes, forbs, mosses, lichens, and liverworts. These plants either mostly or completely cover the surface of the ground. The soils are typically moist, fine-grained, and often hummocky.[14]

Atmospheric plumes

Bennett Island plumes are a phenomenon in the arctic that had been a mystery to atmospheric scientists for decades until it was finally explained by a collaborative, post-cold war United States and Russian expedition in the 1990s. For years, scientists observed large, sometimes hundreds of miles long plumes emanating from the northeast coast of Russia over the remote Bennett Island and scientists hypothesized that the plumes were caused by volcanoes, gas plumes or even Soviet cold war testing before satellite observations revealed them to be meteorological in origin.[15]

The most popular theory among scientists was that the plumes were formed when clathrates – methane, trapped and frozen into a crystalline structure similar to ice by a combination of low temperatures and high pressures — melted and released methane gas. These gas deposits can melt, bubble to the surface and erupt like a geyser into the atmosphere.

Due to remaining cold-war tensions, and the Soviet military’s desire to protect the secrecy of submarine facilities, western scientists were only able to observe the plumes remotely via satellite. The melting permafrost/clathrate hypothesis was unable to be tested until spring of 1992, when US and Russian Scientists in Siberia were able to conduct an air-borne expedition conduct a sampling of the plume and surprisingly found no methane.

Scientists had initially dismissed the meteorological explanation of the clouds because the plumes only seemed to be unique to Bennett Island and not the other, similar islands, and because it was thought that the 1,000 foot high island was too low to generate orographic clouds. Orographic clouds normally form when air is forced to rise as it passes over a mountain and cools.

Bennett Island plumes form due to the layering of arctic air at different, very cold temperatures. The region is relatively remote, with only warmer polynyas—open water surrounded by sea ice – to potentially provide instability. When air hits the elevated Bennett Island, which behaves like an airplane air foil it rises up, sometimes to over 3 km (2 mi), nucleates, condenses and forms a cloud. The catalyst for the generation of the plumes was difficult to pinpoint because the apparent source region of the plume can appear to shift with time depending on the weakening or intensification of the strength of the wind flowing over the mountain. Consequently, the plumes were determined to be excellent indicators of the location of arctic fronts and jet stream activity.[16]

Presently, the mystery of Bennett Island plumes has not completely been solved; scientists are still seeking an explanation for why the plumes form at an unusually high latitude of over 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) above the mountain tops. Scientists are also studying the dynamics of the island, and why its unique shape is able to generate these plumes.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ Barr, W., 1980, Baron Eduard von Toll's Last Expedition: The Russian Polar Expedition, 1900–1903. Arctic. vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 201–224.

- ↑ Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, US State Department, 2003, Status of Wrangel and other Arctic islands Last visited May 26, 2008.

- ↑ Kos’ko, M.K., B.G. Lopatin, and V.G. Ganelin, 1990, Major geological features of the islands of the East Siberian and Chukchi Seas and the Northern Coast of Chukotka. Marine Geology. vol. 93, pp. 349–367

- ↑ Kos’ko, M.K., 1992, Major tectonic interpretations and constraints for the New Siberian Islands region, Russia Arctic. 1992 Proceedings International Conference on Arctic Margins, International Conference on Arctic Margins, US Marine Management Service, Alaska Region, Anchorage, Alaska, pp. 195–200.

- ↑ Kos’ko, M.K., and G.V. Trufanov, 2002, Middle Cretaceous to Eopleistocene Sequences on the New Siberian Islands: an approach to interpret offshore seismic. Marine and Petroleum Geology. vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 901–919.

- 1 2 3 Glazovskiy, A.F., 1996, Russian Arctic. in J. Jania and J.O. Hagen, eds. Mass Balance of Arctic Glaciers. International Arctic Science Committee (Working Group on Arctic Glaciology) Report No. 5, Faculty of Earth Sciences University of Silesia, Sosnowiec-Oslo, Norway. 62 pp.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Verkulich, S.R., A.G. Krusanov, and M.A. Anisimov, 1992, The present state of, and trends displayed by, the glaciers of Bennett Island in the past 40 years. Polar Geography and Geology. vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 51–57.

- ↑ Alekseev, M.N., 1997, Paleogeography and geochronology in the Russian eastern Arctic during the second half of the Quaternary. Quaternary International. vol. 41–42, pp. 11–15.

- ↑ Anisimov, M.A., and V.E. Tumskoy, 2002, Environmental History of the Novosibirskie Islands for the last 12 ka. 32nd International Arctic Workshop, Program and Abstracts 2002. Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado at Boulder, pp 23–25.

- ↑ Makeyev, V.M., V.V. Pitul’ko, and A.K. Kasparov, 1992, The natural environment of the De Long Archipelago and ancient man in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. Polar Geography and Geology. vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 55–63.

- ↑ Schirrmeister, L., H.-W. Hubberten, V. Rachold, and V.G. Grosse, 2005, Lost world – Late Quaternary environment of periglacial Arctic shelves and coastal lowlands in NE-Siberia. 2nd International Alfred Wegener Symposium Bremerhaven, October, 30 – November 2, 2005.

- ↑ CAVM Team, 2003, Circumpolar Arctic Vegetation Map.. Scale 1:7,500,000. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) Map No. 1. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska.

- 1 2 "Bennett Island plume". Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS), University of Wisconsin – Madison, USA. December 1, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ↑ "LBL physicist solves Cold War mystery". Diane LaMacchia. December 1, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

External links

Media related to Bennett Island at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bennett Island at Wikimedia Commons- Headland, R. K.,1994, OSTROVA DE-LONGA ('De Long Islands'), Scott Polar Research Institute