Bernard Leach

Bernard Howell Leach CH CBE (5 January 1887 – 6 May 1979), was a British studio potter and art teacher.[1] He is regarded as the "Father of British studio pottery".[2]

Biography

Early years (Japan)

Leach was born in Hong Kong, but spent his first years in Japan, until his father, Andrew Leach, moved back to Hong Kong in 1890. Later, he attended the Slade School of Fine Art and the London School of Art, where he studied etching under Frank Brangwyn.[3] Reading books by Lafcadio Hearn, he became interested in Japan.

In 1909 he returned to Japan with his young wife Muriel (née Hoyle) with a view to teaching etching. In Tokyo he gave talks and attended meetings along with Mushanokōji Saneatsu, Shiga Naoya, Yanagi Sōetsu and others from the "Shirakaba-Group",[Sub 1] who were trying to introduce western art to Japan after 250 years of seclusion. In etching, Satomi Ton, Kojima Kikuo, and later Ryūsei Kishida, became pupils of Leach.

About 1911 he attended a Raku-yakipottery party which was his first introduction to ceramics, and through introduction by Ishii Hakutei, he began to study under Urano Shigekichi 浦野繁吉 (1851–1923), who stood as Kenzan 6th in the tradition of potter Ogata Kenzan (1663 -1743). Assisting as interpreter for technical terms was the potter Tomimoto Kenkichi, whom he had met already earlier. From this time Leach wrote articles for the Shirakaba.

1913 he also drafted covers for Shirakaba and "Fyūzan".[Sub 2] Attracted by the Prussian philosopher and art scholar Dr. Alfred Westharp, who at the time was living in Peking, Leach moved to Peking in 1915. There he took on the Name 李奇聞 (for "Leach"), but returned the following year to Japan. – It was the year 1919, when young Hamada Shōji visited Leach for the first time. Leach received a kiln from Kenzan and built it up in Yanagi's garden and called it Tōmon-gama. Now established as a potter, he decided to move to England.

In 1920, before leaving, he had an exhibition in Osaka, where he met the potter Kawai Kanjirō. In Tokyo, a farewell exhibition was organised.

Back in England

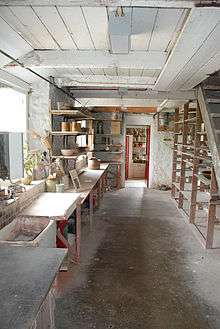

Leach returned to England in 1920 on the invitation of Frances Horne. Horne was establishing a Guild of Handicrafts within the existing artist colony of St Ives in Cornwall. On the recommendation of a family friend, Edgar Skinner, she contacted Leach to suggest that he become the potter within this group. Leach and his wife Muriel were accompanied by the young Hamada Shoji and, having identified a suitable site next to the Stennack river on the outskirts of St Ives, the two established the Leach Pottery in 1920. They constructed a traditional Japanese climbing kiln or 'noborigama', the first built in the West.[4] The kiln was poorly built and was reconstructed in 1923 by Matsubayashi Tsurunosuke. Leach promoted pottery as a combination of Western and Eastern arts and philosophies. His work focused on traditional Korean, Japanese and Chinese pottery, in combination with traditional techniques from England and Germany, such as slipware and salt glaze ware. He saw pottery as a combination of art, philosophy, design and craft – even as a greater lifestyle. A Potter's Book (1940) defined Leach's craft philosophy and techniques, went through many editions and was his breakthrough to recognition.

In 1934, Tobey and Leach travelled together through France and Italy, then sailed from Naples to Hong Kong and Shanghai, where they parted company, Leach heading on to Japan. Leach formally joined the Bahá'í Faith in 1940. A pilgrimage to the Bahá'í shrines in Haifa, Israel, during 1954 intensified his feeling that he should do more to unite the East and West by returning to the Orient "to try more honestly to do my work there as a Bahá'í and as an artist..."[5]

Midlife

Leach advocated simple and utilitarian forms. His ethical pots stand in opposition to what he called fine art pots, which promoted aesthetic concerns rather than function. Popularized in the 1940s after the publication of A Potter's Book, his style had lasting influence on counter-culture and modern design in North America during the 1950s and 1960s. Leach's pottery produced a range of "standard ware" handmade pottery for the general public. He continued to produce pots which were exhibited as works of art.

Many potters from all over the world were apprenticed at the Leach Pottery, and spread Leach's style and beliefs. His British associates and trainees include Michael Cardew, Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie, David and Michael Leach (his sons), Janet Darnell (whom Leach married in 1956) and William Marshall. His American apprentices include Warren MacKenzie (who likewise influenced many potters through his teaching at the University of Minnesota), Byron Temple, Clary Illian and Jeff Oestrich. He was a major influence on the leading New Zealand potter Len Castle who travelled to London to spend time working with him in the mid-1950s. Another apprentice was the Indian potter Nirmala Patwardhan who developed the so-called Nirmala glaze based on an 11th-century Chinese technique. Many of his Canadian apprentices made up the pottery scene of the Canadian west coast during the 1970s in Vancouver. The Cypriot potter Valentinos Charalambous trained with Leach in 1950-51.[6][7]

Leach was instrumental in organising the only International Conference of Potters and Weavers in July 1952 at Dartington Hall, where he had been working and teaching. It included exhibitions of British pottery and textiles since 1920, Mexican folk art, and works by conference participants, among them Shoji Hamada and US-based Bauhaus potter Marguerite Wildenhain. Another important contributor was Japanese aesthetician Soetsu Yanagi, author of The Unknown Craftsman. According to Brent Johnson, "The most important outcome of the conference was that it helped organize the modern studio pottery movement by giving a voice to the people who became its leaders…it gave them [Leach, Hamada and Yanagi] celebrity status…[while] Marguerite Wildenhain emerged from Dartinghall Hall as the most important craft potter in America."[8]

Later years

He continued to produce work until 1972 and never ended his passion for travelling, which made him a precursor of today's artistic globalism. He continued to write about ceramics even after losing his eyesight. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London held a major exhibition of his art in 1977. The Leach Pottery still remains open today, accompanied by a museum displaying many pieces by Leach and his students.

Honours

- Japan Foundation Cultural Award, 1974.[9]

- Companion of Honour, 1973 (UK).[10]

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 1966 (Japan).[11]

- Commander of the Order of the British Empire, 1962.[12]

Edmund de Waal's book

Edmund de Waal, British ceramic artist and Professor of Ceramics at the University of Westminster, had been taught pottery by Geoffrey Whiting, a disciple of Leach, at the King's School, Canterbury.[13] Whilst in Japan de Waal worked on a monograph of Leach, researching Leach’s papers and journals in the archive room of the Japanese Folk Crafts Museum,[14]

De Waal's book on Bernard Leach was published in 1998.[15] He described it as "the first 'de-mystifying' study of Leach."[16] "The great myth of Leach," he said, "is that Leach is the great interlocutor for Japan and the East, the person who understood the East, who explained it to us all, brought out the mystery of the East. But in fact the people he was spending time with, and talking to, were very few, highly educated, often Western educated Japanese people, who in themselves had no particular contact with rural, unlettered Japan of peasant craftsmen".

De Waal noted that Leach did not speak Japanese and had looked at only a narrow range of Japanese ceramics.[Sub 3]

Writings (selected)

- 1940: A Potter's Book. London: Faber & Faber

- New edition, with introductions by Soyetsu Yanagi and Michael Cardew. London: Faber & Faber, 1976, ISBN 978-0-571-10973-9

- 1985: Beyond East and West: Memoirs, Portraits and Essays. New edition, London: Faber & Faber (September 1985), ISBN 978-0-571-11692-8

- 1988: Drawings, Verse & Belief Oneworld Publications; 3rd edition (1988), ISBN 978-1-85168-012-2

Subnotes

- ↑ Shirakaba ="The Birch" (白樺) was an influential cultural magazine at that time.

- ↑ A cultural magazine. Fyūzan = French fusain, charcoal pencil.

- ↑ (1) Leach was not fluent in the Japanese language, but more importantly, he was an educated artist with a keen eye, working in Japan for ten years, much longer than any other western arts and crafts man. (2) When Leach came to Japan in 1909, the everyday potter had already disappeared, due to industrial production of tableware. At that time, his friend Yanagi and others were trying to save expressively this heritage, starting the Mingei-(folklore)-movement. Later in his life, but much before de Waal's book appeared, Leach spent ten years translating Yanagi's book The Unknown Craftsman, together with Japanese friends, into English.

Notes

- ↑ Cortazzi, Hugh. "Review of Emmanuel Cooper's Bernard Leach Life & Work Archived 2 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine., japansociety.org.uk; accessed 16 June 2015.

- ↑ http://collection.britishcouncil.org/collection/artists/leach-bernard-1887

- ↑ "Japan Society". Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ Leach, Bernard. (1990). Hamada, Potter. Foreword by Warren MacKenzie. Kodansha International 1990 [1975]

- ↑ Weinberg, Robert (1999). Spinning the Clay into Stars: Bernard Leach and the Bahá'í Faith, pp. 21, 29.

- ↑ Marion Whybrow, The Leach Legacy: St Ives Pottery and its Influence (1996)

- ↑ Cornwal Artists Index

- ↑ Johnson, Brent, "A Matter of Tradition" in Marguerite Wildenhain and the Bauhaus: An Eyewitness Anthology, (Dean and Geraldine Schwarz, eds.), p. __.

- ↑ Japan Foundation: Awards

- ↑ Bernard Leach archive: bio notes

- ↑ Sims, Barbara R. (1998). Unfurling the Divine Flag in Tokyo, p. 66. Archived 3 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bahá'í Arts Dialogue: Biography notes

- ↑ Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 54, 2003.

- ↑ de Waal, Edmund.The Hare with Amber Eyes: a hidden inheritance. Vintage, 2011, p. 3. ISBN 978-0-09-953955-1.

- ↑ de Waal, Edmund. Bernard Leach. Tate Publishing, 1998. ISBN 978-1-85437-227-7.

- ↑ Bernard Leach; University of Westminster

References

- Olding, Simon. (2010). The Etchings of Bernard Leach, Crafts Study Centre.

- Johnson, Brent. (2007). "A Matter of Tradition"

- Cooper, Emmanuel. (2003). Bernard Leach Life & Work. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09929-0 (cloth)

- Johnson, Brent. (2007). "A Matter of Tradition" in Marguerite Wildenhain and the Bauhaus: An Eyewitness Anthology Dean and Geraldine Schwarz, eds.. Decorah, Iowa: South Bear Press. ISBN 978-0-9761381-2-9 (cloth)

- Watson, Oliver. (1997). Bernard Leach: Potter and Artist, London: Crafts Council.

- Weinberg, Robert. (1999). Spinning the Clay into Stars: Bernard Leach and the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: George Ronald Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85398-440-5 (paper)

- Ohara Museum of Art/Asahi Shimbun (1980): An Exhibition of the Art of Bernard Leach. Catalogue in Japanese.

- Sōetsu Yanagi: The Unknown Craftsman. Foreword by Shōji Hamada. Adapted by Bernard Leach. Kodansha International, 1972.

- Leach, Bernard. (1990). Hamada, Potter. Foreword by Warren MacKenzie. Kodansha International 1990 [1975].

External links

| Library resources about Bernard Leach |

| By Bernard Leach |

|---|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bernard Leach. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bernard Leach |

- Leach Pottery

- Further information

- Studio Pottery

- Leach Source Collection and Bernard Leach Archive held at the Crafts Study Centre and hosted online by the Visual Arts Data Service (VADS)

- Historic Leach pottery at Stoke-on-Trent Museums

- "Accidental Masterpiece". Ceramics. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- "Bernard Leach, 'Cup and Saucer'". Ceramics. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 9 December 2007.