Biological oceanography

Biological oceanography is the study of how organisms affect and are affected by the physics, chemistry, and geology of the oceanographic system. Biological oceanography mostly focuses on the microorganisms within the ocean; looking at how they are affected by their environment and how that affects larger marine creatures and their ecosystem.[1] Biological oceanography is similar to marine biology, but is different because of the perspective used to study the ocean. Biological oceanography takes a bottom up approach (in terms of the food web), while marine biology studies the ocean from a top down perspective. Biological oceanography mainly focuses on the ecosystem of the ocean with an emphasis on plankton: their diversity (morphology, nutritional sources, motility, and metabolism); their productivity and how that plays a role in the global carbon cycle; and their distribution (predation and life cycle).[1][2][3] Biological oceanography also investigates the role of microbes in food webs, and how humans impact the ecosystems in the oceans.[1]

History

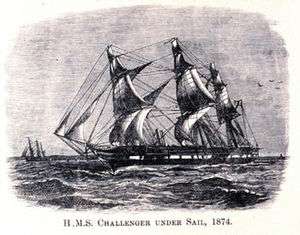

The Challenger Expedition was pivotal to biological oceanography and oceanography in general. The Challenger Expedition was headed by Charles Wyville Thomson in 1872-1876[1] The expedition also included two other naturalists, Henry N. Moseley and John Murray. Prior to the expedition, the ocean was, although interesting to many, considered an unpredictable and mostly life-less body of water and this expedition made them rethink this stance on the ocean This expedition was at the behest of The Royal Society in order to see if they would be able to lay cables at the bottom of the ocean. They also brought the equipment to collect data about the biological, chemical, and geological properties of the ocean in a systematic way.[1] They mapped the oceanic sediment and collected data[1] The data collected in this voyage proved that there was life in deep waters (5500 meters) and that the composition of water in the ocean is consistent.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lalli, Carol M., and Timothy R. Parsons. "Introduction." Biological Oceanography: An Introduction. First Edition ed. Tarrytown, New York: Pergamon, 1993. 7-21. Print.

- ↑ Menden-Deuer, Susanne. "Course Info." OCG 561 Biological Oceanography. Web. 22 Oct. 2014. <http://www.gso.uri.edu/ocg561/>.

- ↑ Miller, Charles B., and Patricia A. Wheeler. Biological Oceanography. Second ed. Chinchester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. Print.