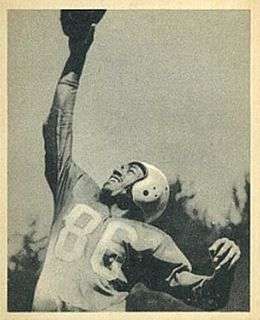

Bob Mann (American football)

| |

| Date of birth | April 8, 1924 |

|---|---|

| Place of birth | New Bern, North Carolina |

| Date of death | October 21, 2006 (aged 82) |

| Place of death | Detroit, Michigan |

| Career information | |

| Position(s) | Wide receiver |

| Height | 5 ft 11 in (180 cm) |

| Weight | 172 lb (78 kg) |

| College | Hampton Institute, Michigan |

| Career history | |

| As player | |

| 1948–1949 | Detroit Lions |

| 1950–1954 | Green Bay Packers |

| Honors | Packers Hall of Fame |

| Career stats | |

| |

Robert "Bob" Mann (April 8, 1924 – October 21, 2006) was an American football end. A native of New Bern, North Carolina, Mann played college football at Hampton Institute in 1942 and 1943 and at the University of Michigan in 1944, 1946 and 1947. He broke the Big Ten Conference record for receiving yardage in 1946 and again in 1947. Mann later played professional football in the National Football League (NFL) for the Detroit Lions (1948–1949) and Green Bay Packers (1950–1954). He was the first African American player for both teams.

Mann led the NFL in receiving yardage (1,014 yards) and yards per reception (15.4) in 1949. Mann was asked to take a pay cut after the 1949 season and became a "holdout" when the Lions opened practice in July 1950. He was traded to the New York Yankees in August 1950 and released three weeks later. Mann charged that he had been "railroaded" out of professional football for refusing to take a pay cut. He signed with the Green Bay Packers near the end of the 1950 NFL season and was the Packers' leading receiver in 1951. He remained with the Packers through the 1954 season. He was inducted into the Green Bay Packers Hall of Fame in 1988.

Mann later became a lawyer and practiced law in Detroit.

Early years

Mann was born in New Bern, the county seat of Craven County, North Carolina, in 1924. His father, Dr. William Mann, was a physician, and his mother, Clara Mann, was a supervisor of elementary schools in Craven County.[1] Mann began his football career at West Street High School in New Bern.[1]

College football

Hampton Institute

In 1941, Mann enrolled at Hampton Institute (now known as Hampton University), a historically black university located in Hampton, Virginia. He joined the school's football team, and as a sophomore, he scored 45 of Hampton's 99 points while playing at the left end position. He scored three touchdowns in Hampton's final game against Virginia Union.[2]

University of Michigan

Mann transferred to Michigan in 1944. He later recalled that his transfer had more to do with academics than football. His father hoped his son would follow him into the medical profession and believed it would be easier to get into medical school if his son attended a university that had a medical school.[3]

Mann later recalled that, upon his arrival in the fall of 1944, Ann Arbor was "a conservative city," noting, "There were some places we (black students) couldn't go."[3] Mann worked in a restaurant near campus to help pay his way through college.[3] He joined the football team and was one of two African-American players (Gene Derricotte was the other) on the 1944 Michigan Wolverines football team.[4] Mann took a year off for military service and returned to Michigan in 1946.[3]

Mann became a starter at the left end position for Fritz Crisler's 1946 and 1947 Michigan Wolverines football teams. In a 2005 profile of Mann's role in integrating football, The Michigan Chronicle wrote:

"Despite the fact that Mann was a standout receiver, earning second-team All-American honors, he was routinely kept on the bench for the first few plays of every game, some say, because there were those at Michigan who did not want to bear the stigma of including a Negro player in its starting lineup. Despite his two-play hiatus at the beginning of games, Bob Mann went on to become one of the University of Michigan's greatest receivers. "[3]

The contention that Mann was "routinely" kept out of the starting lineup for racial reasons, however, is not supported by University of Michigan records which show that an African-American started at the left end position in 6 of 9 games during the 1946 season, with Len Ford (who was also African-American) starting 4 games and Mann starting 2 games.[5] Further, Gene Derricotte (who was also African-American) started 5 games for the 1946 team at the left halfback position.[5] And in 1947, Mann was the starting left end in 8 of 10 games for the Wolverines.[6] Derricotte and Ford also started games for the 1947 Michigan team.[6]

In November 1946, Mann worked his way into the starting lineup and had big games against Wisconsin, Minnesota and Ohio State. In a 28–6 win over Wisconsin, he caught two touchdown passes in the first quarter—a 13-yard pass from Bump Elliott and a 27-yard pass from Bob Chappuis.[7] He also caught touchdown passes from Chappuis against Minnesota and Ohio State.[8][9] Mann also made a diving catch on a 17-yard pass from Chappuis at the Ohio State 3-yard line to set up another Michigan touchdown.[9] During the 1946 season, Mann set a new Big Ten Conference record with 13 receptions for 284 yards.[10][11]

As a senior in 1947, Mann starred on Crisler's undefeated national championship team.[6] During the 1947 season, Mann caught 12 passes for 302 yards and three touchdowns. He also ran for 129 yards on 15 end-around plays.[12] Against Stanford, Mann caught a 61-yard touchdown pass from Chappuis on Michigan's second play from scrimmage. The Chicago Daily Tribune described the plays as follows: "Stanford today was like a boxer taking a Joe Louis knockout punch before having a chance to get his hands up. On the second play after the opening kickoff, Bob Chappuis hurled a touchdown pass to dusky Bob Mann for 61 yards."[13]

Against Pitt, he scored Michigan's first touchdown on a 70-yard pass from Chappuis in the second quarter; he scored again in the second half against Pitt on a 22-yard touchdown pass from Jack Weisenburger.[14]

After the 1947 season, Mann and fellow Michigan end, Len Ford, played in the East-West college all-star game at Gilmore Stadium in Los Angeles; both caught touchdown passes in the game.[15] Mann was also selected by the Associated Press as a first-team end for its All-Big Nine team.[16] He was also selected as a second-team All-American by the Associated Press.[17]

Professional football

Detroit Lions

Signing with the Lions

In February 1948, Mann traveled to New York and met with New York Yankees coach Ray Flaherty. Mann said at the time that he would like to play for the Yankees, but was reluctant to agree to any terms as he was expecting to receive feelers from several other teams in the All-America Football Conference and National Football League.[18] In April 1948, Mann signed with the Detroit Lions of the NFL.[12] Mann's first NFL contract was for $7,500 and a $2,500 bonus, considered to be "solid NFL money in those days."[3] At the time, Detroit coach Bo McMillin said, "We're tickled to get Mann. We've been after his name on a Detroit contract ever since I came here as a coach.[19] We know he will be a valuable professional performer."[12]

Mann was also hired as a spokesman for the Goebel Brewing Company in Detroit's black community. The Lions' president, Edwin J. Anderson, was also president of Goebel, which sponsored Detroit Lions and Detroit Tigers radio broadcasts.[3]

1948 season

As a rookie in 1948, Mann became the first African-American to play for the Lions; halfback Mel Groomes also played for the Lions in 1948.[20] He appeared in all 12 games for the Lions, but was not included in the starting lineup in any of the Lions' games in 1948. Despite his role as a "backup," Mann finished the season with 33 catches for 560 yards, ranking him 7th in the NFL in receiving yards and 4th in yards per reception.[21]

In December 1948, Mann joined Jesse Owens' Olympians professional basketball team in Cleveland. He had played two years of basketball at Hampton Institute but did not play basketball at Michigan.[22]

1949 season

In the pre-season prior to the 1949 NFL season, the Lions played an exhibition game against the Philadelphia Eagles in New Orleans. Coach McMillin met with the Lions' three African-American players (Mann, Groomes and Wally Triplett) before the trip. He explained that there had never been an interracial game in New Orleans. McMillan said he did not think he should break the prohibition and that the three of them would also not be permitted to stay with the team at the hotel.[3] McMillan offered to let the three attend the game and sit on the bench, but Mann declined. Interviewed in 2005, he recalled the incident:

"I said if I can't play in the game I don't want to sit on the bench. ... Bo could've ended all that. He was supposed to be Mr. Great Liberal. But he didn't do it. He just passed it by. He could've been a big guy, a big fellow, but he didn't do it. I've never forgotten that. Don't tell me how liberal Bo was; he wasn't. He had a chance to be a hero, step up to the plate, but he didn't do it."[3]

In Mann's second season in the NFL, the Lions had a new quarterback in Frank Tripucka. Following a team outing, Mann overheard Tripucka's wife complaining that too many receivers were dropping balls. Mann told Mrs. Tripucka to tell her husband to throw the ball to him, saying, "I don't drop passes."[3] On December 11, 1949, Mann was credited with 8 catches for 182 yards and two touchdowns (including a 64-yard touchdown pass from Tripucka in the first quarter and a 41-yard touchdown pass in the fourth quarter) against the Green Bay Packers.[23] The mark tied his own single-game NFL record for receiving yardage.[24] After the game, Mann's wife, described as "an ardent football fan," pointed out to statistician Nick Kerbawy that her tally sheet showed that her husband caught nine passes. Kerbawy ran back through the play-by-play account of the game and discovered she was right.[24][25]

During the 1949 season, Mann led the NFL with 1,014 receiving yards and yards per catch (15.4).[26] He also finished second in receptions with 66 (Tom Fears set an NFL record in 1949 with 77 receptions).[26][27] At the time, Mann's totals in receiving yards and receptions both ranked as the third-highest single-season totals in NFL history.[28]

Despite leading the NFL in receiving yards, Mann was not selected by the United Press for either its first- or second-team All-NFL team. Instead, the UP named him to its "Honorable Mention" team.[29]

Salary dispute in 1950

During the off-season in 1950, the Lions asked Mann to take a $1,500 pay cut from $7,500 to $6,000.[26][30] Mann objected and held out, refusing to sign a 1950 contract with the Lions.[31] Adding fuel to the negotiations, the African-American community in Detroit had called for a boycott of Goebel beer, after a bid by an African-American group for a distributorship in Detroit's black community had been rejected.[30] Mann recalled that Goebels/Lions president Anderson was under the mistaken impression that Mann had met with representatives of the losing bidder concerning the boycott. Mann recalled one meeting at which Anderson "left the room to run cool water on his wrists as a way to calm his anger."[3]

Trade to the New York Yankees

On July 31, 1950, Mann became a "hold out" when he failed to show up on the first day of practice for the Lions.[3][32] that same day, his position as a spokesman for Goebel was terminated.[30] Four days later, he was sent to the New York Yankees in payment for quarterback Bobby Layne.[33] The Lions had previously traded fullback Camp Wilson for Layne, but Wilson refused to report to the Yankees.[32] Mann later recalled that Yankees' coach Red Strader was upset about the trade. Despite a good training camp, Mann received little playing time in exhibition games. John Rauch, a rookie quarterback, told Mann that he had been ordered not to throw to him. The day after Rauch threw a 53-yard touchdown pass to Mann in a pre-season game against the Washington Redskins, Mann was released by the Yankees. He was not picked up by any other team.[3]

Charges of blackballing

Through the months of September and October 1950, Mann was jobless.[26] At the end of October 1950, Mann publicly charged that he had been "railroaded" out of professional football.[26] He claimed that, despite leading the NFL in receiving yards in 1949, the Lions had asked him to take a 20% pay cut. After he objected, he contended that the NFL had taken a "hands off" policy toward him. Mann publicly stated, "I must have been blackballed -- it just doesn't make sense that I'm suddenly not good enough to make a single team in the league.[26] The Lions' response to Mann's charge was a statement that they "want something more from an end than pass-catching ability."[28]

In the fall of 1950, the Michigan Chronicle, an African-American newspaper in Detroit, also questioned the treatment of Mann. Bill Matney wrote in the Chronicle:

"Has a 'freeze' been put on Bob Mann? Mann was expected to have his best year in 1950. He played a total of three minutes in four exhibition games. Officially, Mann has been told by the New York Yanks that he is 'too small to make the team.' Consider the following - the previous year he was considered one of the best receivers in the league. Rival coaches were comparing him to the great Don Hutson in pass catching ability, and shiftiness. Still, after a great year, he was asked to take a pay cut from $8,000 to $6,500. However, after his release, not one NFL team has indicated any interest in picking him up...Many fans believe Mann to be the victim of a 'league fix,' a situation which may be created by team owners which spells 'finis' to the grid career of the player in question...They [fans] are still wondering why such a superior player as Mann in 1949, would not be wanted by any team in the NFL just nine months later. Fans are wondering if outside forces or a situation in which he became innocently involved, have created a 'boycott' which has driven Mann right out of the league."[3]

Green Bay Packers

Mann was signed by the Green Bay Packers on November 25, 1950.[34] On November 26, 1950, he appeared in the Packers' final home game against the San Francisco 49ers, becoming the first African-American to play for the Packers.[35][36] In 1951, Mann led the Packers with 50 catches, 696 receiving yards and eight touchdowns; he also ranked 4th in the NFL in both receptions and receiving yards in 1951.[21][36] He caught three touchdown passes in an October 1951 game against the Philadelphia Eagles.,[37]

Mann remained with the Packers through the 1954 NFL season.[21] Lee Remmel, who worked for the Packers in public relations and served as a team historian, described Mann as "on the small side" (5 feet 11 inches, 175 pounds), but a "nifty and productive wide receiver."[1] Green Bay Gazette sports writer Art Daley recalled a story involving Mann and teammate Dick Afflis, who later became known in professional wrestling as "Dick the Bruiser." The Packers stayed at a Baltimore hotel that would not allow Mann to stay with the team on account of a policy against allowing African-American guests. When Mann left to go to another hotel, the 252-pound Afflis left with him. When a cab driver told Afflis that he would not drive Mann because of his race, Afflis grabbed the driver by the shirt and said, "You will take him wherever he wants to go."[1] Daley also recalled how he had protested the hotel not accepting Mann and Mann calmed him down by saying with a shrug, "That's just politics."

In November 1955, Mann filed a $25,000 breach of contract suit against the Packers. Mann charged he was released illegally after sustaining a knee injury in an exhibition game against the Eagles.[38][39]

Mann was inducted into the Green Bay Packers Hall of Fame in 1988.[36] At the time of his death, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel recalled Mann as one of the players who undid "the myth of white superiority in football."[40] The Journal Sentinel wrote:

"It sounds incredible now, given pro football today, but at one time a myth held sway that black men couldn't play as well as white men. That myth helped to justify the National Football League's practice of recruiting only whites. A player who helped make a lie of the myth was Bob Mann, an African-American who integrated the Green Bay Packers in 1950. In 1948, he and Melvin Groomes had done the same for the Detroit Lions. ... Mann pioneered the idea that skin color does not limit talents."[40]

Later years

Mann later attended law school, graduating from the Detroit College of Law in 1970.[41] He worked as a defense lawyer in Detroit and headed Robert Mann & Associates.[20] Mann's law office was located a few blocks from the Detroit Lions' Ford Field. At the Lions' first regular season game at Ford Field on September 22, 2002, Mann was the Lions' honorary captain.[1]

Mann died in October 2006 at age 82.[20] Pro Football Hall of Famer Lem Barney said of Mann, "Bob was a great example to everyone. He gave of himself to the city and the entire community."[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "New Bern's Mann established several sports firsts". Sun Journal, New Bern, N.C. January 16, 2010. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Bob Mann Scores 45 Points: Sophomore Left End Paces Pirates in Football Tallying". The Afro American. December 8, 1942.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Michael Ranville, Gregory Eaton (October 26 – November 1, 2005). "Bob Mann arrives in Detroit after stellar career at U of M". The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit, Michigan. p. C1.

- ↑ "1944 Michigan Football Roster". University of Michigan, Bentley Historical Library. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- 1 2 "1946 Football Team". University of Michigan, Bentley Historical Library. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "1947 Football Team". University of Michigan, Bentley Historical Library. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Wolverines Tip Badgers, 28-6: Bob Mann Scores Twice on Passes in First Period of Tilt". The Milwaukee Journal. November 16, 1946.

- ↑ "Michigan Defeats Minnesota, 21 to 0". Reading Eagle. November 3, 1946.

- 1 2 Wilfred Smith (November 24, 1946). "Michigan Routs Ohio, 58–6; Indiana, Minnesota Win". Chicago Daily Tribune.

- ↑ Wilfrid Smith (December 22, 1946). "COLLEGES HAVE GREATEST YEAR FOR FOOTBALL". Chicago Daily Tribune.

- ↑ "MICHIGAN SHIFTS MANN". Chicago Daily Tribune. September 19, 1947.

- 1 2 3 "Detroit Lions Sign Bob Mann". St. Petersburg Times. April 23, 1948.

- ↑ Edward Prell (Oct 5, 1947). "Stanford Gets 49 to 13 Jolt at Michigan". Chicago Daily Tribune.

- ↑ "Michigan Steamroller Pulverizes Pitt, 69 to 0". The Milwaukee Journal. October 12, 1947.

- ↑ Dick Hyland (January 19, 1948). "3083 See West Grids Top East". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Four Wolverines, Three Illini Named on All-Conference Team; Indiana, Wisconsin, Purdue and Minnesota Each Places One Man on the First Eleven Selected by Coaches of Big Nine". The New York Times. November 24, 1947.

- ↑ "Irish, Michigan Rule Roost on AP All-America". Chicago Daily Tribune. December 3, 1947.

- ↑ "Bob Mann, Ford Weigh Pro Football Careers". Baltimore Afro-American. February 7, 1948.

- ↑ McMillin became the Lions' head coach in 1948.

- 1 2 3 "Bob Mann dies; first African American to play on Lions". Michigan Chronicle. Detroit, MI. Oct 25–31, 2006. p. C1.

- 1 2 3 "Bob Mann profile". pro-football-reference.com. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Detroit Gridder To Join Cagers". San Antonio Express. December 19, 1948.

- ↑ "Packers End Season With 21 To 7 Loss". The Sheboygan (Wis.) Press. December 12, 1949.

- 1 2 "Wife Keeps Eye On Grid Hubby". Syracuse Herald-American. December 25, 1949.

- ↑ "Mrs. Bob Mann Finds Record-Book Error". THE HOLLAND MICHIGAN EVENING SENTINEL. December 14, 1949.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "BOB MANN AIMS CHARGE THAT HE WAS 'RAILROADED' AT NFL". Los Angeles Times (UP story). November 1, 1950.; via United Press. "Mann Asserts Pro Loop Blackballed His Services: Former Michigan End, Top Pass receiver in 1949, Says He Can't Get a Job Now", The Milwaukee Journal, October 31, 1950. Accessed September 27, 2010.

- ↑ "RAMS' FEARS TOPS NFL PASS CATCHERS". Los Angeles Times. February 23, 1950.

- 1 2 Dan Daly (June 28, 2007). "Old pain left behind in NFL". The Washington Times. p. C.01.

- ↑ "Four Rams Selected on All-NFL Team". Los Angeles Times. December 13, 1949.

- 1 2 3 Charles K. Ross (2001). Outside the Lines: African Americans and the Integration of the National Football League. NYU Press. pp. 123–124.

- ↑ "Lions Send Mann to Grid Yankees". Los Angeles Times (AP story). August 6, 1950.

- 1 2 "Lions Send Bob Mann To Yanks for Layne". IRONWOOD DAILY GLOBE, IRONWOOD, MICH. August 5, 1950.

- ↑ "Lions Send Bob Mann to Yanks to Pay for Layne". Chicago Daily Tribune (AP story). August 5, 1950.

- ↑ "Green Bay Packers Sign End Bob Mann". Wisconsin State Journal (AP story). November 26, 1950.

- ↑ Cliff Christl (January 12, 1999). "Packers are ahead of the game in diversity: Green Bay has made great strides in race relations since Wolf's arrival". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Milwaukee, Wis. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 "FIRST BLACK PACKER DIES". Madison Capital Times, Madison, Wisconsin. October 24, 2006. p. D.2.

- ↑ "Green Bay Aerial Circus Upsets Eagles, 37–24: Bob Mann Scores Three Touchdowns". The LaCrosse Tribune. October 15, 1951.

- ↑ "Mann Files $25,000 Suit Against Packers". Ironwood Daily Globe (AP story). November 24, 1955.

- ↑ "Suit Filed by Packers' Mann Goes to Detroit". Chicago Daily Tribune. January 5, 1956.

- 1 2 "Weekly laurels and laments". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. October 28, 2006. p. A.12.

- ↑ Michael Ranville, Gregory Eaton (Nov 2–8, 2005). "Will America ever right all that is wrong in its history?". The Michigan Chronicle. Detroit, MI. p. C1.