Book size

The size of a book is generally measured by the height against the width of a leaf, or sometimes the height and width of its cover.[2] A series of terms is commonly used by libraries and publishers for the general sizes of modern books, ranging from folio (the largest), to quarto (smaller) and octavo (still smaller). Historically, these terms referred to the format of the book, a technical term used by printers and bibliographers to indicate the size of a leaf in terms of the size of the original sheet. For example, a quarto (from Latin quartō, ablative form of quartus, fourth[3]) historically was a book printed on a sheet of paper folded twice to produce four leaves (or eight pages), each leaf one fourth the size of the original sheet printed. Because the actual format of many modern books cannot be determined from examination of the books, bibliographers may not use these terms in scholarly descriptions.

Book formats

In the hand press period (up to about 1820) books were manufactured by printing text on both sides of a full sheet of paper and then folding the paper one or more times into a group of leaves or gathering. The binder would sew the gatherings (sometimes also called signatures) through their inner hinges and attached to cords in the spine to form the book block. Before the covers were bound to the book, the block of text pages was sometimes trimmed along the three unbound edges to open the folds of the paper and to produce smooth edges for the book. When the leaves were not trimmed, the reader would have to cut open the leaf edges using a knife.

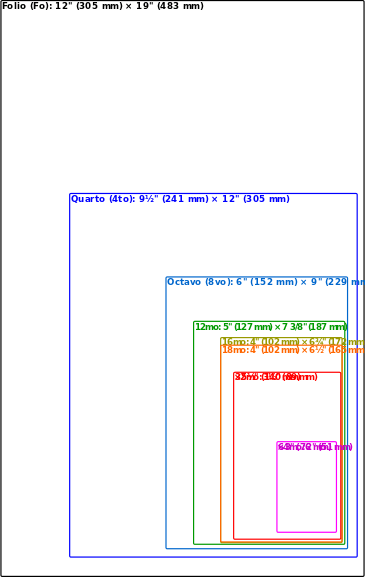

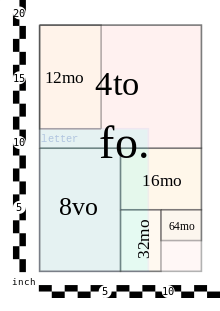

Books made by printing two pages of text on each side of a sheet of paper, which is then folded once to form two leaves or four pages, are referred to as folios (from Latin, foliō, ablative of folium, leaf[3]). Those made by printing four text pages on each side of a sheet of paper and folding the paper twice to form a gathering containing four leaves or eight pages are called quartos (fourths). Similarly, books made by printing eight pages of text on each side of a sheet, which was then folded three times to form gatherings of eight leaves or sixteen pages each, are called octavos. The size of the resulting pages in these cases depends, of course, on the size of the full sheet used to print them and how much the leaves were trimmed before binding, but where the same size paper is used, folios are the largest, followed by quartos and then octavos.[4]:80–81 The proportion of leaves of quartos tends to be squarer than folios or octavos.[5]:164

These various production methods are referred to as the format of the book. These terms are often abbreviated, using 4to for quarto, 8vo for octavo, and so on. The octavo format, with eight leaves per gathering, has half the page size of the quarto format before trimming. Smaller formats include the duodecimo (or twelvemo), with twelve leaves per sheet and pages one-third the size of the quarto format, and the sextodecimo (or sixteenmo), with sixteen leaves per sheet, half the size of the octavo format and one quarter the size of the quarto. The vast majority of books were printed in the folio, quarto, octavo or duodecimo formats.[4]:82

There are many variations in how such books were produced. For example, folios were rarely made by simply binding up a group of two leaf gatherings; instead several printed leaf pairs would be inserted within another, to produce a larger gathering of multiple leaves that would be more convenient for binding.[5]:30–31 For example, three two-leaf printed sheets might be inserted in a fourth, producing gatherings of eight leaves or sixteen pages each. Bibliographers still refer to such books as folios (and not octavos) because the original full sheets were folded once to produce two leaves, and describe such gatherings as folios in 8s. Similarly, a book printed as an octavo, but bound with gatherings of four leaves each, is called an octavo in 4s.[5]:28

In determining the format of a book, bibliographers will study the number of leaves in a gathering, their proportion and sizes and also the arrangement of the chain lines and watermarks in the paper.[4]:84–107

In order for the pages to come out in the correct order, the printers would have to properly lay out the pages of type in the printing press. For example, to print two leaves in folio containing pages 1 through 4, the printer would print pages 1 and 4 on one side of the sheet and, after that has dried, print pages 2 and 3 on the other side. If a printer was printing a folio in 8s, as described above, he would have to print pages 1 and 16 on one side of a leaf with pages 2 and 15 on the other side of that leaf, etc. The arrangement of the pages of type in the press is referred to as the imposition and there are a number of methods of imposing pages for the various formats, some of which involve cutting the printed pages before binding.[4]:80–110

- See Further reading for more on imposition schemes.

Modern book production

As printing and paper technology developed, it became possible to produce and to print on much larger sheets or rolls of paper and it may not be apparent (or even possible to determine) from examination of a modern book how the paper was folded to produce them. For example, a modern novel may consist of gatherings of sixteen leaves, but may actually have been printed with sixty-four pages on each side of a very large sheet of paper.[6]:429 Similarly, the actual printing format cannot be determined for books that are perfect bound, where every leaf in the book is completely cut out (i.e., not conjugate to another leaf as in gatherings) and is glued into the spine. Modern books are commonly called folio, quarto and octavo based simply on their size rather than the format in which they were actually produced, if that can even be determined. Scholarly bibliographers may describe such books based on the number of leaves in each gathering (eight leaves per gathering forming an octavo), even where the actual number of pages printed on the original sheet is unknown[4]:80–81 or may reject the use of these terms for modern books entirely.[note 1]

Today, octavo and quarto are the most common book sizes, but many books are produced in larger and smaller sizes as well. Other terms for book size have developed, an elephant folio being up to 23 inches tall, an atlas folio 25 inches, and a double elephant folio 50 inches tall.

Records

According to Guinness World Records, as of 2003 the largest book in the world was Bhutan: A Visual Odyssey Across the Last Himalayan Kingdom by Michael Hawley, which measures 1.5 m × 2.1 m (4.9 ft × 6.9 ft).[7] In 2012 it has been superseded by the book titled This the Prophet Mohamed made in Dubai, UAE, its size is 5 m × 8 m (16 ft × 26 ft).[8]

The largest published book is an edition of The Little Prince printed in Brazil in 2007, its size is 2 m × 3.1 m (6.6 ft × 10.2 ft).[9]

The smallest book is Teeny Ted from Turnip Town measured 0.07 mm × 0.10 mm (0.0028 in × 0.0039 in).[10]

Paper sizes

During the hand press period, full sheets of paper were manufactured in a great variety of sizes which were given a number of names, such as pot, demy, foolscap, crown, etc.[11][12] These were not standardized and the actual sizes varied depending on the country of manufacture and date.[4]:67–70, 73–75

The size and proportions of a book will thus depend on the size of the original sheet of paper used in producing the book. For example, if a sheet 19 inches by 25 inches is used to print a quarto, the resulting book will be approximately 12.5 inches tall and 9.5 inches wide, before trimming. Because the size of paper used has differed over the years and localities, the sizes of books of the same format will also differ. A typical octavo printed in Italy or France in the 16th Century thus is roughly the size of a modern mass market paperback book, but an English 18th-century octavo is noticeably larger, more like a modern trade paperback or hardcover novel.

Common formats and sizes

United States

The following table is adapted from the scale of the American Library Association,[1][13] in which size refers to the dimensions of the cover (trimmed pages will be somewhat smaller, often by about ¼ inch or 5 mm[2]). The words before octavo signify the traditional names for unfolded paper sheet sizes. Other dimensions may exist as well.[12][14]

Book formats and corresponding sizes Name Abbreviations Leaves Pages Approximate cover size (width × height) inches cm folio 2º or fo 2 4 12 × 19 30.5 × 48 quarto 4º or 4to 4 8 9½ × 12 24 × 30.5 Imperial octavo 8º or 8vo 8 16 8¼ × 11½ 21 × 29 Super octavo 8º or 8vo 8 16 7 × 11 18 × 28 Royal octavo 8º or 8vo 8 16 6½ × 10 16.5 × 25 Medium octavo 8º or 8vo 8 16 6½ × 9¼ 16.5 × 23.5 octavo 8º or 8vo 8 16 6 × 9 15 × 23 Crown octavo 8º or 8vo 8 16 5⅜ × 8 13.5 × 20 duodecimo or twelvemo 12º or 12mo 12 24 5 × 7⅜ 12.5 × 19 sextodecimo or sixteenmo 16º or 16mo 16 32 4 × 6¾ 10 × 17 octodecimo or eighteenmo 18º or 18mo 18 36 4 × 6½ 10 × 16.5 trigesimo-secundo or thirty-twomo 32º or 32mo 32 64 3½ × 5½ 9 × 14 quadragesimo-octavo or forty-eightmo 48º or 48mo 48 96 2½ × 4 6.5 × 10 sexagesimo-quarto or sixty-fourmo 64º or 64mo 64 128 2 × 3 5 × 7.5

See also

Notes

Further reading

A number of imposition schemes for different formats may be found in:

- Voet, Leon (1972). "Appendix 8: Impositions and folding schemes". The management of a printing and publishing house in Renaissance and Baroque. The Golden Compasses: a history and evaluation of the printing and publishing activities of the Officina Plantiniana at Antwerp (the history of the house of Plantin-Moretus). Volume 2. Translated by Raymond H. Kaye. New York: Abner Schram. ISBN 9780839000044. Retrieved 2014-09-11.

- Gaskell (1972),[4] pages 88–107

Additional tables and discussion of American book formats and sizes may be found in:

- Caspar, Carl Nicolaus (1889). "Book sizes (in "Part VI: Theory and practice of the book trade and kindred branches", "c. A vocabulary of terms and phrases in English, German, French, Italian, Dutch, Latin, etc., employed in literature, the graphic arts and the book, stationery and printing trades, etc.")". Caspar's directory of the American book, news and stationery trade. Milwaukee: C. N. Caspar's Book Emporium. pp. 1310–1312 – via Google Books.

- Roberts (1982),[2] available online

- AbeBooks. "Guide to book formats".

- Trussel, Stephen. "Book Sizes". Books and book collecting.

References

- 1 2 Thompson, Elizabeth Hardy, ed. (1943). A. L. A. glossary of library terms, with a selection of terms in related fields. American Library Association. p. 151. ISBN 9780838900000.

- 1 2 3 Roberts, Matt; Etherington, Don (1982). "Book sizes". Bookbinding and the conservation of books: a dictionary of descriptive terminology. Library of Congress. ISBN 9780844403663. Retrieved 2014-09-10 – via Conservation OnLine, operated by the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works.

- 1 2 Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gaskell, Philip (1972). A New Introduction to Bibliography (1st ed.). Clarendon Press.

- 1 2 3 McKerrow, Ronald Brunlees (1927). McKitterick, David, ed. An Introduction to Bibliography for Literary Students. Clarendon Press.

- 1 2 Bowers, Fredson (1949). Principles of Bibliographical Description (1st ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Associated Press (2003-12-16). "Guinness: Scientist creates world's largest book". CNN. Archived from the original on 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ↑ "Largest book". Guinness World Records.

- ↑ "Largest book published". Guinness World Records.

- ↑ "Smallest reproduction of a printed book". Guinness World Records.

- ↑ Ringwalt, John Luther, ed. (1871). "Dimensions of Paper". American Encyclopaedia of Printing. Philadelphia: Menamin&Ringwald. pp. 139–140.

- 1 2 Savage, William (1841). "Paper". A Dictionary of the Art of Printing. New York: Burt Franklin. pp. 560–566.

- ↑ Levine-Clark, Michael; Carter, Toni M., eds. (2013). ALA glossary of library and information science (4th ed.). Chicago, Ill.: American Library Association. p. 38. ISBN 9780838911112.

- ↑ Ambrose, Gavin; Harris, Paul (2015). The Layout Book (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury. pp. 76–77.