George Joseph Smith

| George Joseph Smith | |

|---|---|

|

George Joseph Smith | |

| Born |

George Joseph Smith 11 January 1872 Bethnal Green, London, England, United Kingdom |

| Died |

13 August 1915 (aged 43) Maidstone, Kent, England |

| Cause of death | Execution by Hanging |

| Other names | Brides in the Bath Murderer |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Killings | |

| Victims | 3 |

Span of killings | 1912–1914 |

| Country | England, United Kingdom |

Date apprehended | 23 March 1915 |

George Joseph Smith (11 January 1872 – 13 August 1915) was an English serial killer and bigamist. In 1915 he was convicted and subsequently hanged for the slayings of three women, the case becoming known as the "Brides in the Bath Murders". As well as being widely reported in the media, the case was significant in the history of forensic pathology and detection. It was also one of the first cases in which similarities between connected crimes were used to prove deliberation, a technique used in subsequent prosecutions.

Early life and marriages

The son of an insurance agent, George Joseph Smith was born in Bethnal Green, London. He was sent to a reformatory at Gravesend, Kent, at the age of nine and later served time for swindling and theft. In 1896, he was imprisoned for 12 months for persuading a woman to steal from her employers. He used the proceeds to open a baker's shop in Leicester.

In 1898, he married Caroline Beatrice Thornhill (under another alias, Oliver George Love) in Leicester; it was his only legal marriage (although he also married another woman bigamously the following year). They moved to London, where she worked as a maid for a number of employers, stealing from them for her husband. She was eventually caught in Worthing, Sussex, and sentenced to 12 months. On her release, she incriminated her husband, and he was imprisoned in January 1901 for two years. On his release, she fled to Canada. Smith then went back to his other wife, cleared out her savings, and left.

In June 1908, Smith married Florence Wilson, a widow from Worthing. On 3 July, he left her, but not before taking £30 drawn from her savings account and selling her belongings from their Camden residence in London. On 30 July in Bristol, he married Edith Peglar, who had replied to an advertisement for a housekeeper. He would disappear for months at a time, saying that he was going to another city to ply his trade, which he claimed was selling antiques. In between his other marriages, Smith would always come back to Peglar with money.

In October 1909, he married Sarah Freeman, under the name George Rose Smith. As with Wilson, he left her after clearing out her savings and selling her war bonds, with a total take of £400. He then married Bessie Munday and Alice Burnham. In September 1914, he married Alice Reid, under the alias Charles Oliver James. In total, Smith entered into seven bigamous marriages between 1908 and 1914. In most of these cases, Smith went through his wives' possessions before he disappeared.

Two similar deaths

In January 1915, Division Detective Inspector Arthur Neil received a letter from a Joseph Crossley, who owned a boarding house in Blackpool, Lancashire. Included with the letter were two newspaper clippings: one was from the News of the World dated before Christmas, 1914, about the death of Margaret Elizabeth Lloyd (née Lofty), aged 38, who died in her lodgings in 14 Bismarck Road, Highgate, London (later renamed Waterlow Road). She was found in her bathtub by her husband, John Lloyd, and their landlady.

The other clipping contained the report of a coroner's inquest dated 13 December 1913, in Blackpool. It was about a woman named Alice Smith (née Burnham), who died suddenly in a boarding house in that seaside resort while in her bathtub. She was found by her husband George Smith.

The letter, dated 3 January, was written by Crossley, the landlord of Mr and Mrs Smith, on behalf of Crossley's wife and a Mr. Charles Burnham, who both expressed their suspicion on the striking similarity of the two incidents and urged the police to investigate the matter.

The hunt

On 17 December, Neil went to 14 Bismarck Road, where Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd had taken lodgings. He found it hard to believe that an adult like Mrs. Lloyd could have drowned in such a small tub, especially since the tub was three-quarters full when she was found. He then interviewed the coroner, a Dr. Bates, who had signed the death certificate, and asked if there were signs of violence on the woman. There were none except for a tiny bruise above the left elbow.

Upon further investigation, Neil learned that a will had been made on the 18th, three hours before Margaret Lloyd died, and the sole beneficiary was her husband who had submitted the will to a lawyer "for settlement". In addition, she had withdrawn all her savings on that same day.

On 12 January, Dr. Bates called Neil. He had had an inquiry from the Yorkshire Insurance Company regarding the death of Margaret Lloyd. She had, three days before she was married, taken out a life insurance policy for £700, with her husband John Lloyd as sole beneficiary. Neil promptly asked the doctor to delay his reply. At the same time, he requested more information on the Smith case from the Blackpool Police. Similarly, the late Mrs. Smith had earlier taken out a life insurance policy, and made a will in her husband's favour, and she took the lodgings in Blackpool only after Mr. Smith inspected the bathtub.

Neil asked the coroner to issue a favourable report to the insurance company. He was counting on the suspect to get in touch with his lawyer, and the office was watched day and night. On 1 February, a man fitting Lloyd/Smith's description appeared. Neil introduced himself and asked him whether he was John Lloyd. After Lloyd answered in the affirmative, Neil then asked him whether he was also George Smith. The man denied it vehemently. Neil, already sure that John Lloyd and George Smith were the same man, told him that he would take him for questioning on suspicion of bigamy. The man finally admitted that he was indeed George Smith, and was arrested.

Spilsbury enters the case

When Smith was arrested for the charge of bigamy and suspicion of murder, the pathologist Bernard Spilsbury was asked to determine how the women died.[1] Although he was the Home Office pathologist and acted mainly in a consulting capacity, he was also available for direct assistance to the police force.

Margaret Lloyd's body was exhumed, and Spilsbury's first task was to confirm drowning as the cause of death; and if so, whether by accident or by force. He confirmed the tiny bruise on the elbow as noted before, as well as two microscopic marks. Even the evidence of drowning was not extensive. There were no signs of heart or circulatory disease, but the evidence suggested that death was almost instantaneous, as if the victim died of a sudden stroke. Poison was also seen as a possibility, and Spilsbury ordered tests on its presence. Finally, he proposed to Neil that they run some experiments in the very same bathtub in which Margaret died. Neil had it set up in the police station.

Newspaper reports about the "Brides in the Baths" began to appear. On 8 February, the chief police officer of Herne Bay, a small seaside resort in Kent, had read the stories, and sent Neil a report of another death which was strikingly similar to the other two.

A third victim

A year before Burnham's death in Blackpool, one Henry Williams had rented a house with no bath in 80 High Street, for himself and his wife Beatrice "Bessie" Munday, whom he married in Weymouth, Dorset, in 1910. He then rented a bathtub seven weeks later. He took his wife to a local doctor, Frank French, due to an epileptic fit, although she was only complaining of headaches, for which the doctor prescribed some medication. On 12 July 1912, Williams woke French, saying that his wife was having another fit. He checked on her, and promised to come back the following afternoon. However, he was surprised when, on the following morning, he was informed by Williams that his wife had died of drowning. The doctor found Bessie in the tub, her head underwater, her legs stretched out straight and her feet protruding out of the water. There was no trace of violence, so French attributed the drowning to epilepsy. The inquest jury awarded Williams the amount of £2,579 13s 7d (£2,579.68p), as stipulated in Mrs Williams' will, made up five days before her death.

Neil then sent photographs of Smith to Herne Bay for possible identification, and then went to Blackpool, where Spilsbury was conducting an autopsy of Alice Smith. The results were the same as with Margaret Lloyd: the lack of violence, every suggestion of instantaneous death, and little evidence of drowning. Furthermore, there were no traces of poison on Margaret Lloyd. Baffled, Spilsbury routinely took measurements of the corpse and had the tub sent to London.

Back in London, Neil had received confirmation from Herne Bay. "Henry Williams" was also "John Lloyd" and "George Smith". This time, when Spilsbury examined Bessie Williams, he found one sure sign of drowning: the presence of goose pimples on the skin. As with the other two deaths, the tub in which Mrs Williams had died was sent to London.

Solution

For weeks Spilsbury pondered over the bathtubs and the victims' measurements. The first stage of an epileptic fit consists of a stiffening and extension of the entire body. Considering her height (five feet, seven inches) and the length of the tub (five feet), the upper part of her body would have been pushed up the sloping head of the tub, far above the level of the water. The second stage consists of violent spasms of the limbs, which were drawn up to the body and then flung outward. Therefore, no one of her size could possibly get underwater, even when her muscles were relaxed, in the third stage: the tub was simply too small.

Using French's description of Bessie Williams when he found her in the bathtub, Spilsbury reasoned that Smith must have seized her by the feet and suddenly pulled them up toward himself, sliding the upper part of the body underwater. The sudden flood of water into her nose and throat might cause shock and sudden loss of consciousness, explaining the absence of injuries and minimal signs of drowning.

Neil hired several experienced female divers of the same size and build as the victims. He tried to push them underwater by force but there would be inevitable signs of struggle. Neil then unexpectedly pulled the feet of one of the divers, and her head glided underwater before she knew what happened. Suddenly Neil saw that the woman was no longer moving. He quickly pulled her out of the tub and it took him and a doctor over half an hour to revive her. When she came to, she related that the only thing she remembered was the rush of water before she lost consciousness. Thus was Spilsbury's theory confirmed.

George Joseph Smith was charged for the murders of Bessie Williams, Alice Smith and Margaret Lloyd on 23 March 1915.

Trial and legal legacy

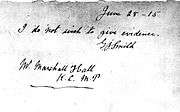

On 22 June, the trial began at the Old Bailey. The prosecuting Counsel were Archibald Bodkin (later Director of Public Prosecutions), Cecil Whiteley (later KC) and Travers Humphreys.[2][3] Although he could only be tried for the murder of Bessie Munday in accordance with English law, the prosecution used the deaths of the other two to establish the pattern of Smith's crimes; this was allowed by Mr Justice Scrutton despite the protests of Smith's counsel, Sir Edward Marshall Hall. Smith decided not to give evidence in his own defence, indicating this to Marshall Hall in a handwritten note.(pictured)

It took the jury about 20 minutes on 1 July to find him guilty; he was then sentenced to death. Marshall Hall appealed on the grounds that the evidence of "system" has been improperly admitted, but Lord Reading LCJ dismissed the appeal,[4] and Smith was hanged in Maidstone Prison by John Ellis.

The use of 'system'—comparing other crimes to the one a criminal is being tried for to prove guilt—set a precedent that was later used in other murder trials. For example, the doctor and suspected serial killer John Bodkin Adams was charged for the murder of Edith Alice Morrell, but the deaths of Gertrude Hullett and her husband Jack were used in the committal hearing to prove the existence of a pattern. This use of 'system' was later criticised by the trial judge when Adams was tried only on the Morrell charge.[5]

Popular culture

In his book Why Britain is at War,[6] Harold Nicolson used the behaviour of George Smith and his repeatedly murderous behaviour as a parallel to Hitler's repeatedly acquisitive behaviour in Europe in the 1930s. In Evelyn Waugh's book Unconditional Surrender, which is set during the Second World War, General Whale is referred to as "Brides-in-the-bath" because all the operations he sponsored seemed to require the extermination of all involved.

The Smith case is mentioned in Dorothy L. Sayers' mysteries, Unnatural Death [7] and Busman's Honeymoon [8] It was also mentioned in Agatha Christie's novels A Caribbean Mystery and The Murder on the Links. It is also mentioned on Patricia Highsmith's novel A Suspension of Mercy at page 63: "Not for him the Smith brides-in-a-bath murders for peanuts." The crimes of George Joseph Smith also feature in William Trevor's novel The Children of Dynmouth in which the sociopathic protagonist plans to re-enact the crimes as part of the community's Easter Fete. On page 273 of Monica Ferris's novel "The Drowning Spool," it mentions "a certain George Joseph Smith" who is discovered through the work of "a very clever forensic investigator back then." Margery Allingham's short story "Three Is a Lucky Number" (1955) adapts the events and refers to James Joseph Smith and his Brides. The Smith case was dramatised on the radio series The Black Museum in 1952 under the title of The Bath Tub. Czechoslovak Television's series Adventures of Criminology (1990), based on famous criminal cases in which new methods of investigation were used, depicts this case in the episode Reconstruction.

There was also The Brides in the Bath (2003), a British TV movie made by Yorkshire Television, starring Martin Kemp as George Smith and the play Tryst by Karoline Leach, first produced in New York in 2006, starring Maxwell Caulfield and Amelia Campbell.[9] This story is the basis for the play The Drowning Girls by Beth Graham, Charlie Tomlinson, Daniela Vlaskalic.[10] In the episode "Echoes of the Dead" from the British TV detective series Midsomer Murders,[11] DCI Barnaby solves a series of murders that revolve around "Brides-in-the-bath" murders with multiple references to the case including Smith, Spilsbury and the forensics of the period.

For some years his waxwork was exhibited in the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussauds in London.

See also

References

- ↑ Andrew Rose, Lethal Witness, Sutton Publishing 2007, Kent State University Press 2009

- ↑ Wilson, Colin; Patricia Pitman (1984). Encyclopedia of Murder. London: Pan Books. pp. 577–580. ISBN 0-330-28300-6.

- ↑ Watson, ER (Ed) (1922). The Trial of George Joseph Smith. London: William Hodge.

- ↑ Brian P. Block; John Hostettler (2002). Famous cases: nine trials that changed the law. Waterside Press. pp. 225–30. ISBN 1-872870-34-1.

- ↑ Devlin, Patrick. Easing the passing: The trial of Doctor John Bodkin Adams, London, The Bodley Head, 1985.

- ↑ "Why Britain is at War" (1939) by Harold Nicolson, republished as ISBN 978-0-14-104896-3

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Unnatural Death, Chapter 8.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, [Busman's Honeymoon], Chapter 5.

- ↑ "TRYST". wild-reality.net. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ↑ John Coulbourn (16 October 2009). "Girls' tale slips slowly beneath the water". Toronto Sun.

- ↑ Midsomer Murders: Echoes of the Dead, Series 14 (2011-2012), Episode 3.

- Jane Robins, The Magnificent Spilsbury and the Case of the Brides in the Bath, 2010, John Murray

- J.H.H. Gaute and Robin Odell, The New Murderer's Who's Who, 1996, Harrap Books, London

- Eric R. Watson (ed), Trial of George Joseph Smith, Notable British Trials series, 1922, W. Hodge

- Herbert Arthur, All the Sinners, 1931, London

- Nigel Balchin, The Anatomy of Villainy, 1950, London

- Dudley Barker, Lord Darling's Famous Cases, 1936, London

- Carl Eric Bechhofer Roberts, Sir Travers Humphreys: His Career and Cases, 1936, London

- William Bolitho, Murder for Profit, 1926, London

- Ernest Bowen-Rowlands, In the Light of the Law, 1931, London

- Douglas G. Browne and E. V. Tullett, Sir Bernard Spilsbury: His Life and Cases, 1951, London

- Albert Crew, The Old Bailey, 1933, London

- Harold Dearden, Death under the Microscope, 1934, London

- Douglas G. Browne; E. V. Tullett (1955). Bernard Spilsbury: his life and cases. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

External links

- Trial report on Networked Knowledge, based on Notable British Trials