Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church

| Brown Memorial Park Avenue Presbyterian Church | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country |

|

| Denomination | Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) |

| Website | http://www.browndowntown.org |

| History | |

| Dedicated | December 4, 1870 |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) |

Hutton and Murdock (1870) Ralph Adams Cram (1931) |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Clergy | |

| Minister(s) |

Rev. Andrew Foster Connors, Senior Pastor Rev. Kate F. Connors, Parish Associate Rev. Dr. Ed Richardson, Parish Associate Tim Hughes, Associate Pastor for Youth Michael Britt, Minister of Music Dr. John Walker, Minister of Music Emeritus |

| Laity | |

| Religious education coordinator | Rachel Cunningham |

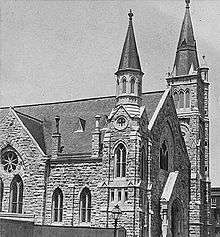

Brown Memorial Park Avenue Presbyterian Church of Baltimore, Maryland, U.S., is a large, Gothic Revival-style church built in 1870 and located at Park and Lafayette Avenues in the city's Bolton Hill section. Named in memory of a 19th-century Baltimore financier, the ornate church is noted for its exquisite stained glass windows by renowned artist Louis Comfort Tiffany, soaring vaulted ceiling, and the prominent persons associated with its history. Maltbie Babcock, who was the church's pastor 1887–1900, wrote the familiar hymn, This is My Father's World.[1] Storied virtuoso concert performer Virgil Fox was organist at Brown Memorial early in his career (1936–1946).[2]

Called "one of the most significant buildings in this city, a treasure of art and architecture" by Baltimore Magazine, the church underwent a $1.8 million restoration between 2001–2003.[3][4] It is part of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) denomination.

History

The Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church building was dedicated on December 4, 1870, in memory of George Brown, chairman of the Baltimore-based investment firm, Alex. Brown & Sons, and one of the founders of the pioneering Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1827.[5] Construction was funded by a gift of $150,000 from his widow, Isabella McLanahan Brown, an amount equivalent to more than $4 million in 2009.[6][7] George Brown was described by a Baltimore historian as a successful businessman and civic leader who "regarded religion as preeminent above all other things and loved his church with all the ardor of his noble nature".[8] John Sparhawk Jones was the church's first pastor, serving from 1870 to 1884. Several of his collected sermons were later published in such books as Seeing Darkly, The Invisible Things, and Saved by Hope.

The church's pastor between 1887–1900 was Maltbie Babcock, who was formally installed on September 28, 1887. His biography in a 1910 encyclopedia described him as "a fluent speaker, with a marvelous personal magnetism which appealed to all classes of people, and the influence of which became in a sense national. His theology was broad and deep ... he reached people in countless ways and exerted everywhere a remarkable personal magnetism ... [having] an unusually brilliant intellect and stirring oratorical powers that commanded admiration".[9] While at Brown, he led fund-raising efforts to assist Jewish refugees from Russia who were victims of an anti-Jewish pogrom.[10] He was also a popular speaker with students at Johns Hopkins University. Under Babcock, the church acquired additional property at North and Madison Avenues for a chapel and Sunday School complex.[11]

When Babcock was called to New York City's Brick Presbyterian Church in 1900, many prominent Baltimoreans, including the faculty of Johns Hopkins University, unsuccessfully implored Babcock to remain at Brown instead of accepting the call to Brick Church.[12][13] Babcock resigned on January 17, 1900, to pastor the Manhattan church but died suddenly the following year at age 42. At his New York funeral, the presiding clergyman eulogized him, "We do not need a candle to show a sunbeam...The work our brother has done – the life he lived speaks for him."[14] A memorial service for the esteemed former pastor was held at Brown Memorial on May 22, described as "impressive" by the New York Times.[11] So inspired was former U.S. Postmaster General James Albert Gary, a member of Brown Memorial, that he chaired a committee to raise $50,000 (the equivalent of $1.4 million in 2009) for construction of a new church in memory of the beloved former pastor.[7][11] More than half of that amount was raised the first day from the wealthy congregation, the New York Times reported, and the new Babcock Memorial Presbyterian Church was soon constructed on Brown Memorial Church's North Avenue property.[11]

Babcock's successor as minister of Brown Memorial, John Timothy Stone, also presided over a large memorial gathering in Baltimore on June 2, 1901, choosing as the text for his address to the throng: "For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also" (Matthew 6:21). Babcock was eulogized at the Baltimore service by various prominent educators, including Daniel C. Gilman, the first president of Johns Hopkins University, John F. Goucher, the founder of Goucher College, and Francis L. Patton, president of Princeton University.[10] A poem by Babcock was published posthumously the following year by his wife as the familiar hymn, This is My Father's World.[1]

The sanctuary was enlarged in 1905 with the addition of a transept and several Tiffany windows while Stone was minister.[6] Further significant development occurred in 1931 under T. Guthrie Speers, with the addition of the current chancel designed by notable architect Ralph Adams Cram and the installation of the present 4-manual pipe organ by Ernest M. Skinner.[15] Speers had a popular ministry at Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church from 1928 to 1957. He began an outreach program to Baltimore's Jewish community, occasionally exchanging pulpits with local rabbis.

After Speers' retirement in 1957, John Middaugh was minister from 1958 to 1968. Middaugh was a regular panelist for ten years on the weekly television program To Promote Goodwill, an interfaith discussion of social and religious issues produced by WBAL-TV and broadcast worldwide on the Voice of America.[16] He was also in the forefront of the civil rights movement in the early 1960s. Along with William Sloan Coffin and dozens of other clergymen and civil rights activists, Middaugh was arrested in a clash with police at Baltimore's Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in July 1963 over efforts to desegregate the popular attraction.[17][18]

Membership peaked at 1,336 in 1952 but subsequently declined in the late 1950s as much of the city's population migrated to the suburbs. In response, a portion of the congregation decided in 1956 to build a church in the suburban Woodbrook area north of Baltimore. Other members wished to remain at the Bolton Hill location, prompting a decision to operate one church at two locations, with a shared ministerial staff. In the early 1970s, the church began a tutoring program for neighborhood children and a "Meals on Wheels" service under then-ministers Iain Wilson, pastor, and Clinton C. Glenn Jr., assistant minister.[19] In 1980, the congregations of the two churches voted for separation. The original Bolton Hill church was subsequently constituted as "Brown Memorial Park Avenue", to distinguish it from "Brown Memorial Woodbrook", when the separation was completed in October, 1980.[15]

The immediate past minister of the church is Roger J. Gench, pastor from 1990 to 2002, who is now pastor of historic New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C.

The full list of senior ministers from 1870 to present is:

| Minister | Years of appointment |

|---|---|

| John Sparlock Jones | 1870–1884 |

| Frank Wadeley Gunsaulus | 1885–1887 |

| Maltbie Babcock | 1887–1900 |

| John Timothy Stone | 1900–1909 |

| J. Ross Stevenson | 1909–1914 |

| John McDowell | 1915–1921 |

| G. A. Hulbert | 1921–1928 |

| T. Guthrie Speers | 1928–1957 |

| John Middaugh | 1958–1968 |

| Iain Wilson | 1968–1973 |

| Charles Ehrhardt | 1975–1980 |

| David Malone | 1980–1990 |

| Roger J. Gench | 1990–2002 |

| Andrew Foster Connors | 2004–present |

| Sources: Jane T. Swope, A History of Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church 1870–1995[15] and church website[20] | |

Current ministry

The current pastor of Brown Memorial Park Avenue Church since 2004 is Andrew Foster Connors.[20] A native of Raleigh, North Carolina, he earned a Bachelor of Arts from Duke University and a Master of Divinity degree from Columbia Theological Seminary in 2001. He is a recipient of the prestigious David H. C. Read Preaching Award, named for Presbyterian clergyman and author David H. C. Read of New York City's Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church.[21]

His wife, Kate Foster Connors, whom he met while both were student interns for U.S. Representative David Price, is also an ordained minister and serves as youth director at Brown Memorial. The Connors have two children.[20]

Under the pastorate of Andrew Foster Connors, the church’s historic leadership continues in social justice issues including national peace efforts, a statewide campaign for marriage equality, local efforts to rebuild blighted neighborhoods, and advocacy of after-school programs to invest in the youth of Baltimore. His views on current affairs are frequently reported in the Baltimore Sun daily newspaper. Connors has also taken an active role in dialogues between the Jewish and Christian faith communities.[21]

Music ministry

.jpg)

The current minister of music and organist at Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church since June, 2012, is Michael Britt, who studied music at the Peabody Conservatory and the Conservatoire de Paris. He succeeded Dr. John Walker, an internationally renowned concert organist and CD recording artist, who was minister of music between 2004 and December, 2011. Formerly director of music and organist at Riverside Church in New York City (1983–1992) and Shadyside Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (1992–2005), Walker has a Doctor of Musical Arts degree from Stanford University and is National Vice President of the American Guild of Organists.[22] He was named Minister of Music Emeritus by Brown Memorial in 2012 and continues to perform there occasionally.

Other previous organists include the celebrated virtuoso Virgil Fox, who gained considerable fame as a concert performer and recording artist while at Brown Memorial early in his career, from 1936 to 1946.[2] Later, Richard Ross was also a significant music figure in the life of the congregation, succeeding Fox as choirmaster and organist, while also composing music. Francis Eugene Belt then served as organist for more than 50 years, spanning the 1950s to the late 1990s.[19]

The 4-manual Ernest M. Skinner pipe organ has 2,939 pipes and remains essentially the same today as when it was installed in 1931 and tonally finished by G. Donald Harrison, as Skinner's opus 839.[23] The organ underwent a complete restoration between 2002–2005, with all original 45 ranks of the instrument fully preserved. A 99-memory level Capture System was added to the organ in 2005.[24]

The choir sings a wide range of choral music at Sunday services, from works of classical composers, such as Mozart's Ave verum corpus and choruses by Handel and Johannes Brahms, to spirituals and anthems by 20th-century composers, such as Jane Marshall's My Eternal King. Major choral works are also performed during the year, such as the oratorio Elijah by Felix Mendelssohn, conducted by Walker and accompanied by guest organist Frederick Swann, and Johann Sebastian Bach's cantata, God's time is always the very best time ("Actus Tragicus", BWV106), in the 2008–2009 season. The choir's May, 2009, performance of Elijah has since been released on CD.

Programs and activities

Along with regular worship services on Sundays and holy days, Brown Memorial Park Avenue Church offers various programs of enrichment and outreach, such as concerts, lectures, and study forums. The "Tiffany Series" presents high quality classical concerts as well as distinguished speakers at the church. Speakers have included Harry Belafonte and Marian Wright Edelman, founder of the Children's Defense Fund, who spoke on Children in Peril: What Does Our Faith Require of Us? on March 16, 2008.[25] The series "Wednesday Nights at Brown" offers dinner speakers for adults, such as John Walker's "Christian Hymnody and the Theology Behind It," and arts or music activities for children.

The church is active in numerous missions, both locally and on the national and world scenes. Its Urban Mission committee sponsors the Tutoring Program, the oldest volunteer school tutoring program in the nation, and partners with a local elementary school in a story-reading program and yearly donation of books to all pupils. High school and college age youth participate in "Share," an annual summer missions trip to El Salvador.[25][26] The church also has a longstanding outreach program with the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where Brown Memorial youth and adults conduct summer learning camps for Lakota children.[27]

Stained glass windows

Among the considerable number of stained glass windows, those crafted by Louis Comfort Tiffany in 1905 are especially prized for their vibrancy and exceptional depth.[28] Baltimore City Paper called the church and its collection of a dozen Tiffany windows, "the most magnificent interior space in Baltimore City".[29] During the restoration survey in 2000, various stained glass experts praised the extent and craftsmanship of the windows.[4] As part of the church's $1.8 million restoration project between 2001–2003, all of the stained glass windows were releaded and restored to their original lustre.[3][30] They are:

- The Annunciation to the Shepherds – the birth of the infant Christ is announced by angels to shepherds tending their flocks. Tiffany employed a confetti glass technique for the flames of the shepherds' bonfire as the star of Bethlehem gleams with etched glass.[28]

- The Baptism of Christ – portrays Jesus with John the Baptist at the River Jordan. Mottled glass is used for the area around the water, with a layer of wavy glass over Christ's left foot to create the illusion of looking through water.[28]

- Christ Blessing the Children – the Lord holds a child in his lap, whose face is that of the boy for whom this window was donated as a memorial by his grieving parents.[28][30]

- I am the Way – Jesus walks on tempestuous seas surrounded by storm clouds. Opalescent glass is used to create a glow of light around the figure of Jesus.[30]

- Christ in Gethsemane – portraying Christ praying in the Garden of Gethsemane, surrounded by trees made of stippled glass.[30]

- The young David – the future Israelite king is pictured.

- If I Be Lifted Up – Christ is portrayed in the clouds, with light radiating from behind His head as the penetrating eyes seem to follow the viewer around the nave. An extra layer of mottled glass behind the clouds was used by Tiffany.[29]

- Lead, Kindly Light – the cross at its center is made of etched glass and glows brightly in the rays of the afternoon sun.

- The Holy City – St. John's vision on the isle of Patmos of the "New Jerusalem", as described in Revelation 21:2. Brilliant red, orange, and yellow glass is etched for the sunrise, with textured glass used to create the effect of moving water. Said to be one of the two largest windows (along with The Annunciation to the Shepherds) ever made by the Tiffany Studios, this 58-panel stained glass window honors the church's beloved pastor of the 1880s–1890s, Maltbie Babcock.[29]

- Gabriel – the archangel Gabriel in the clouds, with feathers individually made of opalescent glass by Tiffany.

- John, the Visionary – Wearing a red cloak and having an intense expression, St. John is portrayed by Tiffany in the style of the 17th-century Flemish painter Reubens. The window is made of drapery, opalescent, and mottled glass.[29]

- The New Creation – located at the rear of the church, it is based on the description in Revelation 22:1-2, with stained glass depictions of trees, mountains, and streams of Living Water. At the top is a star morphing into a cross, with rays made of nuggets.[28]

- Brown Memorial's stained glass windows

-

The Annunciation to the Shepherds, by Tiffany

-

The Baptism of Christ, by Tiffany

-

The New Creation, by Tiffany

-

Interior details

-

The Good Shepherd, by Wilbur Burnham, and the organ

References

- 1 2 "Maltbie Davenport Babcock — 1858-1901". cyberhymnal. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- 1 2 Richard Torrence, Marshall Yaeger (2001). Virgil Fox (the Dish) — An Irreverent Biography of the Great American Organist. New York: Circles International. ISBN 0-9712970-0-2.

- 1 2 Elizabeth Evitts (April 2003). ""Window to the Future", Baltimore Magazine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-11. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- 1 2 Tricia Bishop (2003-04-07). "Illuminated by a jewel". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ↑ Dilts, James D. (1993). The Great Road. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2235-8.

- 1 2 "A Brief History". Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- 1 2 "Relative Value of a US Dollar Amount 1774 to Present". Measuringworth. 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ George M. Howard, Monumental City – Its Past History and Present resources.

- ↑ Maltbie Davenport Babcock, The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Supplement I. New York: James T. White (1910 edition).

- 1 2 Memorial service (PDF), Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church, Baltimore, Md., June 2, 1901.

- 1 2 3 4 "In memory of Dr. Babcock" (PDF). The New York Times. May 24, 1901. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Hard Fight for a Minister" (PDF). The New York Times. November 11, 1899. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ↑ Steele, David M. (1902). "The Ministry As A Profession". The World's Work. New York: Doubleday. IV (5): 2287.

- ↑ "Funeral of Rev. Dr. Babcock" (PDF). The New York Times. June 13, 1901. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Jane T. Swope, A History of Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church 1870–1995, Baltimore, Maryland, 1995.

- ↑ Thomas H. O'Connor, Baltimore Broadcasting from A to Z, Baltimore, Md. (1985)

- ↑ "283 Integrationists, Many Clerics, Arrested At Gwynn Oak Park". The Baltimore Sun. July 5, 1963.

- ↑ "March on Gwynn Oak Park". Time magazine. Time (magazine). July 13, 1963. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- 1 2 Rasmussen, Frederick N. (February 11, 2009). "Clinton Clair Glenn Jr.". The Baltimore Sun. p. 18.

- 1 2 3 "Staff". Brown Memorial Park Avenue Church. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- 1 2 Rev. Andrew Foster Connors (biography). Baltimore: Brown Memorial Park Avenue Church, 2008.

- ↑ "John Walker profile". Baltimore, Md.: Peabody Institute. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ "Opus 839: Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church". Aeolian-Skinner Archives. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ↑ "The Skinner Organ". Brown Memorial Park Avenue Church. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- 1 2 "The Tidings" (PDF). Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church. March 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ↑ "Santa Maria Marde Del Los Pobres". Brown Memorial Park Avenue Presbyterian Church. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ↑ "The Hau Kola Partnership". Brown Memorial Park Avenue Presbyterian Church. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 L. Irving Pollitt, A History of Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church 1870–1945.

- 1 2 3 4 Joan S. Feldman, Sacred Glass: The Tiffany Windows of Brown Memorial Park Avenue Presbyterian Church. Baltimore: Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church (2005).

- 1 2 3 4 "Tiffany Stained Glass Windows". Brown Memorial Park Avenue Presbyterian Church. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

External links

- Official website

- "John Walker and the Choir of Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church", November 14, 2010, program on Sacred Classics radio broadcast.

Coordinates: 39°18′24″N 76°37′26″W / 39.306667°N 76.623767°W