Rhinella proboscidea

| Rhinella proboscidea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Bufonidae |

| Genus: | Rhinella |

| Species: | R. proboscidea |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhinella proboscidea (Spix, 1824) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Rhinella proboscidea is a species of small South American toads in the family Bufonidae, common in the Amazon rainforest. It is the only species known to practice reproductive necrophilia.[1]

Taxonomy

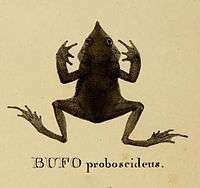

The specific name derives from the Latin proboscis (elephant trunk), in recognition of the toad's prominent beak. It is a member of the R. margaritifera species complex.[2]

The species was first described under the name Bufo proboscideus by Johann Baptist von Spix in 1824.[3] Spix collected the holotype specimen near the Solimões River during his journey to Brazil. It is now held by the Zoologische Staatssammlung München.[4]

In 2006, members of the Bufo margaritifera complex were recognized as the new genus Rhinella, leading to the current name.[5] The merge of another genus into Rhinella left a different species sharing this name (homonymy), which was resolved by renaming the other species Rhinella boulengeri (now Dendrophryniscus proboscideus).[6][7]

Distribution

This toad is found in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical moist lowland forests and intermittent freshwater marshes. It is threatened by habitat loss.[8] It is common in parts of the Amazon rainforest.[2]

Characteristics

Males are 46–54 mm with smooth skin, while females are 46–55 mm with granular skin. The dorsal surface is reddish or dark brown, and typically spattered with black and brown patches. It has a triangular head with a pointed snout, and a brown to gray belly.[9]

This toad is mostly active during the day, sleeping on small seedlings and shrubs at night,[2] but shows nocturnal activity during the breeding period.[10] Its tadpoles are light brown and similar to other R. margaritifera tadpoles.[2] The skin is highly toxic,[11] but predation by a snake (Xenoxybelis argenteus) has nonetheless been observed.[12]

This species is an explosive breeder that reproduces in shallow pools off the edge of streams.[2] The toads gather in these locations for two or three days, where they collectively fertilize thousands of eggs.[1] A typical reproductive period is from March to May, but it could vary depending on rainfall.[2] After heavy rain, choruses of as many as 100 male R. proboscidea calling for a mate have been heard.[2]

Males breed aggressively, approaching any nearby toad and attempting to steal mates from other males already in amplexus. These struggles sometimes result in the female being suffocated.[2] The dead females may be subjected to necrophilia. Males use their front and hind limbs to squeeze the sides of the corpse's belly until oocytes are ejected. The oocytes are then fertilized. In one study, this behavior was observed in five different males. The researchers suggested that the necrophilia was a reproductive strategy, offseting the fitness cost of the female's death. This would make R. proboscidea the only species known to practice reproductively functional, rather than accidental, necrophilia.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 Izzo, T. J.; Rodrigues, D. J.; Menin, M.; Lima, A. P.; Magnusson, W. E. (2012). "Functional necrophilia: a profitable anuran reproductive strategy?". Journal of Natural History. 46 (47-48): 2961–2967. doi:10.1080/00222933.2012.724720.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Menin, M.; Rodrigues, D. J.; Lima, A. P. (2006). "The tadpole of Rhinella proboscidea (Anura: Bufonidae) with notes on adult reproductive behavior". Zootaxa. 1258: 47–56.

- ↑ Spix, Johann Baptist von (1824). Animalia nova sive species novae testudinum et ranarum, quas in itinere per Brasiliam annis 1817-1820. Monachii, F.S. Hübschmanni. p. 52.

- ↑ Glaw, F.; Franzen, M. (2006). "Type catalogue of amphibians in the Zoologische Staatsammlung München" (PDF). Spixiana. 29: 162.

- ↑ Frost, D. R.; et al. (2006). "The amphibian tree of life". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 297: 365.

- ↑ Chaparro, J. C.; Pramuk, J. B.; Gluesenkamp, A. G.; Frost, D. R. (2007). "Secondary homonymy of Bufo proboscideus Spix, 1824, with Phryniscus proboscideus Boulenger, 1882". Copeia. 2007 (4): 1029–1029. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2007)7[1029:shobps]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Frost, Darrel (2014). "Dendrophryniscus proboscideus (Boulenger, 1882)". Amphibian Species of the World 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Coloma, L.A.; Ron, S.; Gascon, C.; Hoogmoed, M. (2004). "Rhinella proboscidea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ↑ Lima, Albertina P.; et al. (2015). "Rhinella proboscidea". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Menin, M.; Waldez, F.; Lima, A. P. (2008). "Temporal variation in the abundance and number of species of frogs in 10,000 ha of a forest in Central Amazonia, Brazil" (PDF). South American Journal of Herpetology. 3 (1): 72.

- ↑ Jovanovic, O.; Vences, M.; Safarek, G.; Rabemananjara, F. C.; Dolch, R. (2009). "Predation upon Mantella aurantiaca in the Torotorofotsy wetlands, central-eastern Madagascar" (PDF). Herpetology Notes. 2: 96.

- ↑ Menin, M. (2005). "Bufo proboscideus. Predation". Herpetological Review. 36 (3): 299.