Bungarribee Homestead

| Bungarribee Homestead | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Ruinous Bungarribee Homestead in 1954. The Italian Cypress, at right, still marks the site. | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Cottage orné |

| Town or city |

Bungarribee Sydney New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°46′44″S 150°52′14″E / 33.7788298442°S 150.8706802940°E |

| Construction started | c1822 - 1827 |

| Demolished | May 1957 |

| Client | John Campbell |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Unknown |

Bungarribee Homestead was a historic house near Eastern Creek, New South Wales built for Colonel John Campbell between 1822 and 1828.[1] The homestead, which was acquired by the Overseas Telecommunications Commission (OTC) and demolished in 1957, gained a reputation for being "possibly Australia's most haunted house".[2]

History

Darug people and the Government Farm

The traditional owners of Bungarribee estate were the Warrawarry group of the Darug people.[3] At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the land around what is now the Sydney suburb of Bungarribee was the site of considerable resistance by the Darug people towards European settlers. As a result of this, and in addition to the fatalities associated with a fatal outbreak of smallpox in the colony from around 1789, by the 1840s there were less than 300 Darug people reported to be living in the area. This equated to less than 10% of the estimated population at the time of European arrival.[1]

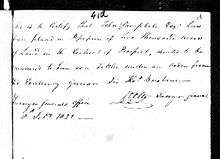

From 1802 until about 1815, the site of the Bungarribee estate was included within the 38,728 acres that made up the much larger Rooty Hill Government Farm.[4] Established by Governor Philip Gidley King to ensure the supply of good pasture for government herds, the farm remained unaltered from its natural state until 1810 when the-then Governor Lachlan Macquarie subdivided the farms into smaller parcels of land for free settlers.[1] Among these settlers was John Campbell of Argylshire, Scotland who is mentioned in the Colonial Secretary's Papers on 8 February 1822 as having taken possession of two thousand acres in the district of Prospect. The Land and Stock Muster of this same year records that Campbell's estate included "2000 acres at Parramatta with 130 acres cleared, 15 acres of wheat, 5 acres of barley and 2 acres of potatoes".[5]

The estate, in reality some distance from Parramatta, was bounded by Eastern Creek in the west, the existing Bungarribee Road in the north, what is now the Great Western Highway in the south, and the approximate line of Reservoir Road in the east.[1]

John Campbell's homestead

John Campbell, a major in the British Army and for whom Bungarribee Homestead was built, arrived in Sydney on 30 November 1821 with his wife, Annabella, and their nine children aboard a sailing ship called the Lusitania.[6] A son, Charles James Fox Campbell, became one of the first European settlers in Adelaide, South Australia. A great-grand grandson, Sir Walter Campbell, would later become a judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland, Chancellor of the University of Queensland, and Governor of Queensland.[7]

No more than four months after their arrival a notice of caution appeared in the classifieds section of the Sydney Gazette, undersigned by Campbell and his neighbour Mr Robert Crawford, asking for the immediate removal of all cattle grazing on “the farms of Armady and Milton, situate on the East Creek, in the District of Prospect … having been lately marked off and located to [Campbell and Crawford]”.[8] At the time, Bungarribee was known as "Armady" or "Armaddy", taking its name from Campbell's home in Argyllshire, Scotland.[9]

Between March 1822 and July 1824 Campbell consolidated his landholdings and renamed the estate “Bungarribee”, which at the time was understood to mean the burial place of an Aboriginal king.[10] This has subsequently been disproven and the word 'Bungarribee' is now thought to have been derived from two Darug words which together can be translated to mean 'creek with cockatoos' or 'creek with campsite'.[1]

The homestead, begun sometime around 1825 and incorporating into its servant’s quarters an earlier cottage from 1822, was not completed in the lifetimes of either John or Annabella Campbell. In November 1826, it was reported that Annabella Campbell died at Bungarribee “after a severe indisposition”.[11] Her death was followed less than twelve months later by that of her husband on 10 October 1827, also at the homestead. Both are buried in the grounds of the Old St John’s Church in Parramatta.[12] At the time Campbell’s estate was cleared in February 1828, Bungarribee still comprised 2,000 acres and was advertised as including a house “scarcely completed at Mr Campbell’s death, [consisting] of a dining room and five bedrooms on the ground floor, and four small rooms in the upper storey”.[13] The conical-roofed tower, a defining feature of the house in subsequent decades, was not completed at the time of the auction and was most likely finished during the ownership of the Icely family from October 1828 until May 1832.[14]

Modifications and decline

The homestead had many owners during the years between 1832 and 1908, after which time it enjoyed more extended periods of occupation by the Walters and Hopkins families.[15] Among its more celebrated tenants were the British East India Company, who assembled horses on the property as remounts for troops in India, and also the pioneer and entrepreneur Benjamin Boyd.[16]

During the early years of the twentieth century, the-then owner Major J. J. Walters broke the estate into smaller parcels of land but remained in residence at the homestead until the 1920s. After the departure of the Major and his family in the early 1920s, the homestead was purchased by Charles W. Hopkins who spent "a large sum" on its restoration.[15] The date of the Hopkins restoration is unknown, however newspaper articles place these changes sometime between 1926 and 1928. In a description of the house from 1926, for instance, a journalist lamented that "neglect and changed conditions conspire with time to wreck this fine old home ... [and that] a more utilitarian age will soon demand its removal".[17] Within a few years, however, the homestead was reported to be "greatly altered; in fact practically re-built, although the old historical features have been preserved".[18]

There is no explanation as to why the house fell, once again, into a state of great disrepair between 1928 and 1935. Within only seven years of the celebrated Hopkins restoration, another journalist described the house as being “with its burden of a century's life, standing like a battered old man, calmly awaiting the call that will write 'finis' in its history”.[1] The condition of the homestead only worsened during the Second World War, during which time the Commonwealth had resumed the property for military purposes, and by the 1950s Bungarribee had become "an isolated wreck" on the Doonside Road.[19] Considerable damage appears to have been done in early 1950, as recorded by students at the Sydney Technical College in December of that year.[10] By this time, much of the homestead’s interior had been destroyed and the rubble footings were beginning to sink. Photographs taken by Barry Wollaston in 1954, now kept by Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, show that most of the windows had been broken and that the roof had begun to collapse.

In 1957, after a failed attempt by the OTC to give the property to the National Trust, the homestead was demolished.[1]

Architecture

The architect of Bungarribee Homestead remains unknown. In The Australian Colonial House, James Broadbent describes the homestead as having been "an L-shaped house with a drum at the junction of the two arms". The "drum", as Broadbent calls it, formed the base of a "circular conical-roofed tower with two single-storeyed verandahed wings radiating from it".[20] In Lost glories : a memorial to forgotten Australian buildings, David Latta states that the tower housed a drawing room on the ground floor and that the upper level was broken into a number of smaller rooms. Due to the curvature of the walls, interior doors in the drawing room were also curved and in this way reminiscent of the foyer in the now-also demolished The Vineyard House at Rydalmere.[4]

The overall impression of the homestead, from its carriageway at least, was that it was "one of the most charming houses built in early colonial New South Wales". A 1932 description of the homestead states that "all the ground floors opened upon stone flagged verandahs, originally draped with trailing roses and creepers. On two sides was an old garden with a carriage drive, and on one side in the midst of a little lawn stood a true lover’s tryst, an old sundial”.[21]

Recognised from some distance away by its tower, as well as being romanticised for its "simple and stately style of humble execution, of broad wall surfaces and long colonnaded verandahs", the house was in fact "a strange hybrid piece of geometry, a semi cylinder married to a triangular prism" that had been designed to some extent around the need for a staircase to its upper level.[22] Subtly Italianate in style, the house has been recognised as being among the earliest influences on the development of the cottage orné style in colonial Australian architecture.

The footings and floor surfaces of the homestead were unearthed during archaeological test excavations in June 2000. Prior to this, the site of the homestead had been marked by above ground remnants of the former garden including bunya pine (Araucaria bidwillii), hoop pine (Araucaria cunninghamii) and pencil pine (Cupressus sempervirens).[1] The site has been subsequently incorporated into a public reserve called Heritage Park within the Sydney suburb of Bungarribee.[23]

Ghosts

The homestead's reputation for being haunted first appeared in print in The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate in 1938.[24] In making reference to "the famous old legend of The Bungarribee Ghost", the article provides one of the only credible indications that the house had been afforded its sinister reputation quite some time prior to this date. Although the alleged supernatural happenings at Bungarribee Homestead were not properly reported until the time of its demolition, there does exist sufficient evidence of several deaths on site that would later form the basis of more well-known accounts of hauntings at the homestead. The most widely reported of these deaths, that of Major Frederick Hovenden in 1845, has more than likely given rise to a story about the ghost of a military officer who took his own life in the iconic Bungarribee tower room. Hovenden, who was indebted to creditors and had disappeared from Sydney as much as two years earlier, was found dead in a remote corner of the estate with the words "Died of Hunger" engraved on the peak of his travelling cap.[25] The tragic account of the man's death seems to have given rise to two far more elaborate tales about the house, both published by the Sydney Morning Herald in February 1957, in which "an officer suicided in a bedroom, bloodstaining the floor" and that of "the frightened boy ...[who] woke up in the night to feel cold hands gripping his throat" and after scooping up his clothes and rushing out of the house "walked miles for help before he could calm down".[2]

The Ghost Guide to Australia recognises Bungarribee Homestead as one of the most haunted in Australia.[26]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Bungarribee Homestead Complex - Archaeological Site". NSW Office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- 1 2 Burke, David (24 February 1957). "Ghosts Upstairs AND Down". The Sun-Herald. p. 21.

- ↑ Attenbrow, Val. Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records. UNSW Press. p. 27. ISBN 1742231160.

- 1 2 Latta, David (1986). Lost glories : a memorial to forgotten Australian buildings. Angus & Robertson. p. 58. ISBN 0207152683.

- ↑ Baxter, Carol, ed. (1988). General muster and land and stock muster of New South Wales 1822. ABGR. ISBN 0949032085.

- ↑ Latta, David (1986). Lost glories : a memorial to forgotten Australian buildings. Angus & Robertson. p. 56. ISBN 0207152683.

- ↑ Barlow, Geoff; Corkery, Jim (2013). "Walter Campbell: A distinguished life". Owen Dixon Society eJournal. Bond University.

- ↑ "Classified Advertising". The Sydney Gazette And New South Wales Advertiser. TWENTIETH, (956). New South Wales, Australia. 15 March 1822. p. 1. Retrieved 13 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ WSM, John. "Col. John Campbell JP (1770-1827) of Lochend and Bungarribee,NSW, Australia". RootsWeb. RootsWeb. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- 1 2 Bungarribee: An old colonial homestead near Doonside in the State of New South Wales. Sydney Technical College. December 1950.

- ↑ "Family Notices". The Sydney Gazette And New South Wales Advertiser. XXIV, (1259). New South Wales, Australia. 15 November 1826. p. 3. Retrieved 13 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Broadbent, James. The Australian colonial house : architecture and society in New South Wales, 1788-1842. Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. ISBN 1875567186.

- ↑ "Classified Advertising". The Sydney Gazette And New South Wales Advertiser. XXVI, (1562). New South Wales, Australia. 29 September 1828. p. 3. Retrieved 13 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Latta, David (1986). Lost glories : a memorial to forgotten Australian buildings. Angus & Robertson. p. 60. ISBN 0207152683.

- 1 2 Latta, David (1986). Lost glories : a memorial to forgotten Australian buildings. Angus & Robertson. p. 63. ISBN 0207152683.

- ↑ "BUNGARRIBEE". The Cumberland Argus And Fruitgrowers Advocate. LXV, (4100). New South Wales, Australia. 13 December 1934. p. 12. Retrieved 13 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "A PAGE FROM THE PAST". Windsor and Richmond Gazette. 38, (2040). New South Wales, Australia. 26 November 1926. p. 16. Retrieved 14 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "BUNGARRIBEE". The Cumberland Argus And Fruitgrowers Advocate. XL, (3449). New South Wales, Australia. 18 May 1928. p. 9. Retrieved 14 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Bungarribee". Sydney Architecture. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Broadbent, James. The Australian colonial house : architecture and society in New South Wales, 1788-1842. Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. ISBN 1875567186.

- ↑ "Lavender and Old Lace". Nepean Times. 50, (2605). New South Wales, Australia. 7 May 1932. p. 7. Retrieved 14 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Broadbent, James. The Australian colonial house : architecture and society in New South Wales, 1788-1842. Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. ISBN 1875567186.

- ↑ "Bungarribee Estate Heritage Park". Clouston Associates. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ "SMOKE CONCERT". The Cumberland Argus And Fruitgrowers Advocate (4408). New South Wales, Australia. 3 March 1938. p. 13. Retrieved 14 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "BODY FOUND IN BUNGARRABBEE BRUSH.". Morning Chronicle. 2, (139). New South Wales, Australia. 1 February 1845. p. 2. Retrieved 14 October 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Davis, Richard (1998). The ghost guide to Australia. Sydney, NSW: Bantam Books. ISBN 0733801498.