Cần Vương movement

| Cần Vương movement | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

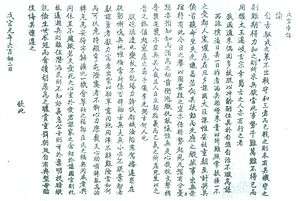

Toàn văn Chiếu Cần Vương | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

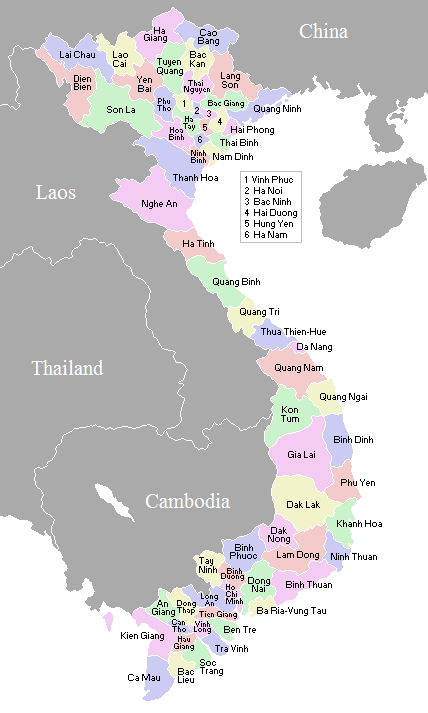

The Cần Vương (Hán tự: 勤王, lit. Aid the King) movement was a large-scale Vietnamese insurgency between 1885 and 1889 against French colonial rule. Its objective was to expel the French and install the boy emperor Hàm Nghi as the leader of an independent Vietnam. The movement lacked a coherent national structure, and consisted mainly of regional leaders who attacked French troops in their own provinces. The movement initially prospered, as there were only a few French garrisons in Annam, but failed after the French recovered from the surprise of the insurgency and poured troops into Annam from bases in Tonkin and Cochinchina. The insurrection in Annam spread and flourished in 1886, reached its climax the following year and gradually faded out by 1889.[1]

French involvement in Vietnam

17th – 18th Century

French involvement in Vietnam begins as early as the 17th century, with missionaries such as Alexandre de Rhodes spreading the Catholic faith.[2] This situation was to remain until the late 18th century, when a popular uprising against heavy taxation and corruption, known as the Tay Son uprising, toppled the ruling Nguyen family in 1776. A Nguyen prince, Nguyen Anh managed to escape. In an attempt to regain power, Nguyen Anh sought the assistance of France through French missionaries in Vietnam. Though he did not receive formal military assistance, he was supplied with sufficient aid by sympathetic merchants and was able to reclaim the throne.[3] Although not officially sanctioned by the French government, this was to heighten French interest in Vietnam and mark the start of increasing intervention.

19th Century – The loss of the South

After regaining the throne in 1802 at the capital city of Hue in central Vietnam, Nguyen Anh reestablished the Confucian traditions and institutes that were overturned during the Tay Son uprising. Having returned to power with the aid of foreigners, this was in order to reassure the scholar-gentry families that comprised much of the government and bureaucracy of a return to the system that guaranteed their privileges. While this helped to legitimize the returning Nguyen dynasty in the eyes of the mandarins and officials, it did little to assuage or address the grievances that sparked the Tay Son uprising.[4]

As a result, the reign of the dynasty was marred by peasant resentment and constant revolts. Discontentment by the oppressed peasants, particularly among the lower-classes, provided fertile grounds for Catholic missionaries, further widening the divide between the Nguyen dynasty and its subjects. The domestic situation would continue to worsen until the 1850s. This had critical implications for Vietnamese resistance to the coming French colonial aggression. It robbed Vietnam of a united front by setting the administration and the people against each other. The resulting mistrust and antagonism would discourage any attempt by the government to move the court out amongst the peasants in the advent of serious foreign incursions, a successful precedent set by previous dynasties. The peasantry would also be deprived of leadership and regional coordination traditionally provided by the royal court.[5]

In 1858, for ostensibly religious reasons, France took military action against Vietnam. French interest in Vietnam had not waned since Nguyen Anh’s request for assistance. After the 1848 revolution, the French government now had sufficient support from commercial, religious and nationalistic sources to stage its conquest of Vietnam. A force led by Admiral Regault de Genouilly attacked and occupied the Vietnamese town of Da Nang. This was followed up with the capture of the Saigon in the Mekong delta region in 1859. However, Vietnamese reinforcements from nearby provinces soon put both French positions under siege. Despite the tenuous situation of the French, Vietnamese forces were unable to force the foreigners out of the country.[6]

This was due in large part to dissention within the royal court on the best approach to deal with the French. One party advocated armed resistance while the other argued for compromise. Most writers concede that the Emperor and many high-ranking officials favoured appeasing the French, through a policy named hoa nghi (peace and negotiation).[7][8] Additionally, for reasons mentioned previously in the article, the dynasty was reluctant to arm or rely on the peasantry, relying instead on the royal troops which could only put up a feeble struggle.

In 1861, the French had managed to consolidate their forces and break the Vietnamese army’s siege of Saigon. To the surprise of the French forces, the defeat of the royal army did not put an end to Vietnamese resistance. Instead, it marked the decline of formal, government led resistance and gave rise to localized popular resistance. Nonetheless, the widespread struggle by the Vietnamese people dealt the French many setbacks.[9]

A key development at this juncture was the transfer of the leadership role from the dynasty to local scholar-gentries. Having witnessed the ineffectiveness of the regular Vietnamese army and the uncertain direction of the royal court, many decided to take matters into their own hands. Organizing villagers into armed bands and planning guerilla raids on French forces, this was in direct contrast to the royal courts’ attempts to make peace. This had the added effect of convincing the French that the Hue court had lost control of its forces in the Mekong delta region and thus offering any concessions was pointless.[10]

In 1862, the Nguyen dynasty signed the Treaty of Saigon. It agreed to surrender Saigon and 3 southern provinces to France which were to become known as Cochinchina. Some authors [11] point to the dynasty’s need to put down rebellions in the North as a reason territories were ceded in the South. Regardless of the reason, the regular army was to withdraw from the surrendered provinces, leaving the popular resistance movement to the French.

Truong Dinh was a striking example of a resistance leader. He first gained prominence and military position during the siege of Saigon and also for his military accomplishments immediately after the defeat of the Vietnamese army. Despite the order to withdraw, Dinh remained in the region at the behest of this subordinates and also for patriotic reasons, echoing the sentiments of fellow scholar-gentries. However, the popular resistance lacked coordination across regions and also could not provide spiritual encouragement, tools that only the Nguyen dynasty had access too.[12]

Up to 1865, the Nguyen dynasty followed its policy of compromise and continued attempting to reclaim the 3 southern provinces through diplomacy. This was despite warnings by the French that they would seize the remaining 3 southern provinces if popular resistance, which they referred to as bandits, was not stopped. In 1867, citing the abovementioned reasons, the French took over the remaining 3 southern provinces.[13]

The loss of the South had a momentous effect on Vietnam. First it exposed the weaknesses of the dynasty’s policy of compromise. The few remaining mandarins and scholar-gentry in the region were left with two options, to flee the region permanently or to collaborate with the new overlords. For the people of the delta who had no other option but to stay, the setback was to prove insurmountable. Popular resistance quickly lost all morale and disbanded, with the peasants resigning themselves to nonviolent postures. At this stage, the Nguyen dynasty had lost all allegiance and respect from the Vietnamese in the South.[14][15]

19th century – loss of the north

In 1873, the French, citing restrictions on shipping and led by Francis Garnier, easily captured the northern city of Hanoi, facing little or no organized resistance.[16] Garnier was eventually killed with the aid of the Black Flag Army and the city returned as part of a treaty signed in 1874. However the Nguyen dynasty now faced a loss of support and allegiance from its subjects in the north, similar to what had transpired in the south.

Following actions taken by predecessors, the Nguyen dynasty turned to China for aid. Unsurprisingly, the French took action first in order to avoid being boxed out of north Vietnam.[17] In 1882, a French captain named Henri Rivière repeated Garnier’s feat of taking Hanoi. Rather than preparing the military for increased French aggression, the military was instructed to remain out of sight of the French. Rivière was later killed by the Black Flag Army during a military action; however the dynasty continued sounding out France for new negotiations and sidelining mandarins who still advocated armed resistance.

In 1883, the last of the great Emperors of Vietnam died without an heir. His death resulted in internecine discord among the different factions in Hue. At the same time, having witnessed the reconquest of Hanoi by French forces under Riviere, northern Vietnamese became further disillusioned with the leadership and military effectiveness of the royal court in Huế. Discontentment was amplified by the continued reliance of the royal court on negotiation, despite the willingness of local mandarins and people to take up armed resistance against the French. Dispatches from French commanders confirmed this, praising court representatives for pacifying the Vietnamese around Hue.[18]

The final straw for many Northern Vietnamese came when the French captured the city of Son Tay in 1883 against the combined forces of the Vietnamese, Chinese and Black Flag armies. Subsequently, there were attacks by local Vietnamese in the north on French forces, some even led by former Mandarins in direct defiance of the policy set by Hue.

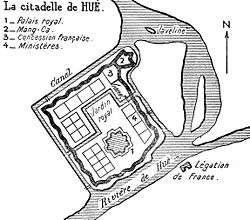

Matters at the royal court of Hue were equally chaotic. The next Emperor, Duc Duc, was in power for barely three months before being deposed due to his unbecoming conduct. The following Emperor Hiep Hoa signed the Treaty of Huế in 1883 after hearing French guns near the capital city. The harsh and derogatory terms of the treaty which subjected Vietnam to French control served to destroy any possible support Hiep Hoa had among the Vietnamese people and at court. He was quickly arrested and killed by the mandarin Ton That Thuyet, who was fervently anti-French.[19]

Thuyet was also secretly drawing upon the economy to make guns for a secret fortress in Tan So. Ton That Thuyet had an associate, Nguyen Van Tuong, who was also considered a problematic mandarin by the French. In 1884, the Emperor Ham Nghi was enthroned as the Emperor of Vietnam. Only twelve years of age, he was easily and quickly dominated by the regents Thuyet and Tuong. By now, the French had realized the obstacles the two mandarins posed and decided to remove them.[20]

Resistance continued growing while the French in Tonkin were distracted by the Sino-French War (August 1884 to April 1885). Matters came to a head in June 1885, when France and China signed the Treaty of Tientsin, in which China implicitly renounced its historic claims to suzerainty over Vietnam.[citation needed] Now freed from external distractions, the French government was determined to gain direct rule over Vietnam. Their agent of choice was General Count Roussel de Courcy.

In May 1885, de Courcy arrived in Hanoi and took control of French military power in order to remove the mandarins Thuyet and Tuong. Most historians agree that de Courcy felt France’s military might was enough to cow the Vietnamese and that he was a strong advocate of the use of force. However, there appears to be contention regarding the French government’s endorsement, if any, of de Courcy’s agenda. Regardless, General de Courcy and an escort of French troops of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps went to Hue and attempted to incite problems.[21]

The 'Huế ambush', July 1885

Having arrived at Hue in July 1885, de Courcy summoned the princes and high mandarins of the royal court to his residence for a discussion on the presentation of his credentials to the Emperor. During the discussion, he demanded that the central gate was to be opened and that the Emperor would have to come down from his throne to greet him. de Courcy also commented on Thuyet's absence from the meeting and suggested that this was due to Thuyet's planning an attack on him. After being told that Thuyet was sick, de Courcy's response was that he should have attended the meeting regardless and threatened to arrest him. Finally, de Courcy rejected the gifts sent by the Emperor and demanded tribute from the Vietnamese.[22]

After the reception, Van Tuong met with Thuyet to discuss the events that had transpired during the discussion. Both mandarins agreed that de Courcy’s intention was to destroy them. Forced into a corner, they decided to stake their hopes on a surprise attack on the French. That very night, the French were attacked by thousands of Vietnamese insurgents during organized by the two mandarins. De Courcy rallied his men, and both his own command and other groups of French troops cantoned on both sides of the citadel of Huế were able to beat off the attacks on their positions. Later, under the leadership of chef de bataillon Metzinger, the French mounted a successful counterattack from the west, fighting their way through the gardens of the citadel and capturing the royal palace. By daybreak the isolated French forces had linked up, and were in full control of the citadel. Angered by what they saw as Vietnamese treachery, they looted the royal palace.[23] Following the failure of the 'Huế ambush', as it was immediately dubbed by the French, the young Vietnamese king Hàm Nghi and other members of the Vietnamese imperial family fled from Huế and took refuge in a mountainous military base in Tan So. The regent Tôn Thất Thuyết, who had helped Hàm Nghi escape from Huế, persuaded Hàm Nghi to issue an edict calling for the people to rise up and "aid the king" ("can vuong"). Thousands of Vietnamese patriots responded to this appeal in Annam itself, and it undoubtedly also strengthened indigenous resistance to French rule in neighbouring Tonkin, much of which had been brought under French control during the Sino-French War (August 1884–April 1885).

The Can Vuong edict was undoubtedly a turning point in Vietnamese resistance to French rule. For the first time, the royal court had a common goal with the peasantry in the north and south, which stood in stark contrast to the bitter divisions between the royal court and its subjects which had hobbled resistance to the French to date. The flight of the Emperor and his court to the countryside amongst the peasants had serious implications for both resistance and collaboration with the French.

First, it brought moral and spiritual authority over to the resistance. Mandarins who chose to work with the French could no longer claim to work on behalf of the court; they had to acknowledge the realities of being tools of a foreign power. On the other hand, mandarins who chose to fight the French even without traditional royal sanction would be greatly relieved to find their decisions vindicated.[24]

Next, the royal court’s flight to the resistance brought about access to two key tools mentioned earlier, regional coordination and spiritual encouragement. Witnessing the hardships endured by the Emperor and his entourage allowed subjects to develop a newfound empathy for their Emperor and increased hatred towards the French. The Emperor could also promulgate edicts across the entire country, calling on subjects in every province and village to rise up and resist the French. Last but not least, the capital city of Hue and the dynasties it harboured had historically played an active role in struggles against Mongol and Chinese aggression. It was the source of leaders and patriotic imagery for the rest of the country. Its participation would link the current resistance movement to previously successful movements and also to future movements up to the modern era.[25]

The Can Vuong Edict

The Emperor proclaims: From time immemorial there have been only three strategies for opposing the enemy: attack, defense, negotiation. Opportunities for attack were lacking. It was difficult to gather required strength for defense. And in negotiations the enemy demanded everything. In this situation of infinite trouble we have unwillingly been forced to resort to expedients. Was this not the example set by King T’ai in leaving for the mountains of Ch’I and by Hsuan-tsung when fleeing to Shu?

Our country recently has faced many critical events. We came to the throne very young, but have been greatly concerned with self-strengthening and sovereign government. Nevertheless, with every passing day the Western envoys got more and more overbearing. Recently they brought in troops and naval reinforcements, trying to force on Us conditions We could never accept. We received them with normal ceremony, but they refused to accept a single thing. People in the capital became very afraid that trouble was approaching.

The high ministers sought ways to retain peace in the country and protect the court. It was decided, rather than bow heads in obedience, sitting around and losing chances, better to appreciate what the enemy was up to and move first. If this did not succeed, then we could still follow the present course to make better plans, acting according to the situation. Surely all those who share care and worry for events in our country already understand, having also gnashed their teeth, made their hair stand on end, swearing to wipe out every last bandit. Is there anyone not moved by such feelings? Are there not plenty of people who will use lance as pillow, thump their oars against the side, grab the enemy’s spears, or heave around water jugs?

Court figures had best follow the righteous path, seeking to live and die for righteousness. Were not Ku Yuan and Chao Tsui of Chin, Kuo Tzu-I and Li Kuang-pi of T’ang men who lived by it in antiquity?

Our virtue being insufficient, amidst these events We did not have the strength to hold out and allowed the royal capital to fall, forcing the Empresses to flee for their lives. The fault is Ours entirely, a matter of great shame. But traditional loyalties are strong. Hundreds of mandarins and commanders of all levels, perhaps not having the heart to abandon Me, unite as never before, those with intellect helping to plan, those with strength willing to fight, those with riches contributing for supplies – all of one mind and body in seeking a way out of danger, a solution to all difficulties. With luck, Heaven will also treat man with kindness, turning chaos into order, danger into peace, and helping thus to restore our land and our frontiers. Is not this opportunity fortunate for our country, meaning fortunate for the people, since all who worry and work together will certainly reach peace and happiness together?

On the other hand, those who fear death more than they love their king, who put concerns of household above concerns of country, mandarins who find excuses to be far away, soldiers who desert, citizens who do not fulfill public duties eagerly for a righteous cause, officers who take the easy way and leave brightness for darkness – all may continue to live in this world, but they will be like animals disguised in clothes and hats. Who can accept such behavior? With rewards generous, punishments will also be severe. The court retains normal usages, so that repentance should not be postponed. All should follow this Edict strictly.

By Imperial Order Second day, sixth month, first year of Ham-Nghi[26]

Attacks on Vietnamese Christians

The Cần Vương movement was aimed at the French, but although there were more than 35,000 French soldiers in Tonkin and thousands more in the French colony of Cochinchina, the French had only a few hundred soldiers in Annam, dispersed around the citadels of Huế, Thuận An, Vinh and Qui Nhơn. With hardly any French troops to attack, the insurgents directed their anger instead against Vietnamese Christians, long regarded as potential allies of the French. Although the numbers remain disputed, it seems likely that between the end of July and the end of September 1885 Cần Vương fighters killed around 40,000 Vietnamese Christians, wiping out nearly a third of Vietnam's Christian population. The two worst massacres took place in the towns of Quảng Ngãi and Bình Định, both south of Huế, in which some 24,000 men, women and children, from a total Christian population of 40,000 were killed. A further 7,500 Christians were killed in Quảng Trị province. In other provinces the number of victims was considerably lower. In many areas the Christians fought back under the leadership of French and Spanish priests, in response to a call from their bishops to defend themselves with every means at their disposal. Outnumbered and on the defensive, the Christians were nevertheless able to inflict a number of local defeats on Cần Vương formations.[27]

French military intervention from Tonkin

.jpg)

The French were slow to respond to the Cần Vương, and for several weeks did not believe the gruesome rumours emanating from Annam. Eventually the scale of the massacres of Christians became clear, and the French belatedly responded. Incursions into Annam were made by troops of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps, which had been reinforced in June 1885 to 35,000 men. Initially forbidden by the French government to launch a full-scale invasion of Annam, General de Courcy landed troops along the vulnerable coastline of central Vietnam to seize a number of strategic points and to protect the embattled Vietnamese Christian communities in the wake of the massacres at Quảng Ngãi and Bình Định. In early August 1885 Lieutenant-Colonel Chaumont led a battalion of marine infantry on a march through the provinces of Hà Tĩnh and Nghệ An to occupy the citadel of Vinh.[28]

In southern Annam, 7000 Christian survivors of the Bình Định massacre took refuge in the small French concession in Qui Nhơn. In late August 1885 a column of 600 French and Tonkinese soldiers under the command of General Léon Prud'homme sailed from Huế aboard the warships La Cocheterie, Brandon, Lutin and Comète, and landed at Qui Nhơn. After raising the siege Prud'homme marched on Bình Định. On 1 September, Vietnamese insurgents attempted to block his advance. Armed only with lances and antiquated firearms and deployed in unwieldy masses which made perfect targets for the French artillery, the Cần Vương fighters were no match for Prud'homme's veterans. They were swept aside, and on 3 September the French entered Bình Định. Three Vietnamese mandarins were tried and executed for complicity in the massacre of Bình Định's Christians.[29] In November 1885 a so-called 'Annam column' under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Mignot set off from Ninh Binh in southern Tonkin and marched down the narrow spine of Vietnam as far as Huế, scattering any insurgent bands in its way.[30]

French political response

The French responded politically to the uprising by pressing ahead with arrangements for entrenching their protectorate in both Annam and Tonkin. They were helped by the fact that there was by no means unanimous support for the Cần Vương movement. The queen mother, Từ Dũ, and other members of the Vietnamese royal family deserted Hàm Nghi and returned to Huế shortly after the uprising began. In September 1885, to undercut support for Hàm Nghi, General de Courcy enthroned the young king's brother Đồng Khánh in his stead. Although many Vietnamese regarded Đồng Khánh as a French puppet king, not all did. One of the most important Vietnamese leaders, Prince Hoàng Kế Viêm, who had been fighting the French for several years in Tonkin, gave his allegiance to Đồng Khánh.

Siege of Ba Đình, January 1887

The Siege of Ba Đình (December 1886 to January 1887) in Thanh Hóa province was a decisive engagement between the insurgents and the French. The siege was deliberately willed by the Vietnamese resistance leader Dinh Cong Trang, who built an enormous fortified camp near the Tonkin-Annam border, crammed it full of Annamese and Tonkinese insurgents, and dared the French to attack him there. The French obliged, and after a two-month siege in which the defenders were exposed to relentless bombardment by French artillery, the surviving insurgents were forced to break out of Ba Đình on 20 January 1887. The French entered the abandoned Vietnamese stronghold the following day. Their total casualties during the siege amounted to only 19 dead and 45 wounded, while Vietnamese casualties ran into thousands. The Vietnamese defeat at Ba Đình highlighted the disunity of the Cần Vương movement. Trang gambled that his fellow resistance leaders would harass the French lines from the rear while he held them from the front, but little help reached him.[31][32]

Intervention from Cochinchina

The catastrophe at Bình Định broke the power of the Cần Vương in northern Annam and Tonkin. The first half of 1887 also saw the collapse of the movement in the southern provinces of Quang Nam, Quảng Ngãi, Bình Định and Phú Yên. For several months after Prud'homme's brief campaign in September 1885 around Qui Nhơn and Bình Định, the Cần Vương fighters in the south had hardly seen a Frenchman. The Tonkin Expeditionary Corps was fully committed in Tonkin and northern Annam, while French troops in Cochinchina were busy dealing with an insurrection against the French protectorate in neighbouring Cambodia. In the early months of 1886 the insurgents took advantage of French weakness in the south to extend their influence into Khánh Hòa and Bình Thuận, the southernmost provinces of Annam. Cần Vương forces were now uncomfortably close to the French posts in Cochinchina, and the French authorities in Saigon at last responded. In July 1886 the French struck back in the south. A 400-man 'column of intervention' was formed in Cochinchina, consisting of French troops and a force of Vietnamese partisans under the command of Trần Bá Lộc. The column landed at Phan Ry, on the coast of Bình Thuận. By September 1886 had won control of the province. In the following spring the French moved into Bình Định and Phú Yên provinces. One of the Cần Vương leaders went over to the French side, and the resistance soon collapsed. By June 1887 the French had established control over the Annamese provinces to the south of Huế. More than 1,500 Cần Vương insurgents laid down their arms, and brutal reprisals, orchestrated by Tran Ba Loc, were taken against their leaders.[33]

Capture of Hàm Nghi, 1888

In 1888, Hàm Nghi was captured and deported to Algeria and the Cần Vương movement was dealt a fatal blow. By losing the King, the movement had lost its purpose and objective. However, resistance to the French from the Can Vuong movement would not die out for another decade or so.

Resistance after 1888

For a few years after Hàm Nghi’s capture, resistance to the French continued, albeit in another form, the Van Than (Scholars’ Resistance). In contrast to the royalist nature of the Can Vuong movement, the Van Than insurrection was wholly focused on resisting the French. The Van Than was led by Confucian scholars who took over the Can Vuong movement after Ham Nghi was captured. By 1892, the Van Than was defeated and its leaders scattered to China and the remaining resistance leaders.[34]

Phan Dinh Phung was one of the final and most remarkable of the Van Than resistance leaders. Together with his troops, he held the province of Ha Tinh in central Vietnam up till 1896. His death from dysentery marked the final chapters of the Can Vuong and Van Than movement.[35]

The last of the Can Vuong resistance leaders was its most famous and one of the few to survive the resistance against the French. De Tham was the leader of an armed band operating in the mountains of north Vietnam, Yen The. He managed to frustrate French attempts to pacify the area up to 1897, when a settlement was reached with the French. The final nail in the coffin of the Can Vuong came about with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1894. Until then, it was relatively easy for partisans, weapons and supplies to cross the Sino-Vietnamese border and support the resistance. With the outbreak of war, Chinese mandarins along the southern border were strictly instructed to avoid antagonizing the French and the border was sealed, along with the fate of the Can Vuong movement.[36]

Summary

The Can Vuong movement was one of firsts and lasts. It was the first resistance movement which saw all strata of Vietnamese society, Royalty, scholar-gentry, peasantry working together against the French. However, this massive, spontaneous support was to prove its weakness as well. Although there were some 50 resistance groups, there was a lack of collaboration and unifying military authority.[37] Though the Can Vuong edict was spread to every part of the country, actions taken by the resistance were never national in scope, instead being restricted to the areas where the scholar-gentry were familiar with and with these actions being undertaken independently of each other.

The Can Vuong movement also marked the fall of the last independent Vietnamese dynasty and with it the scholar-gentry bureaucracy. Yet, the narratives of their struggle against foreign domination continued to live on and were passed down to the next generation, some who witnessed first-hand the weaknesses and strengths of the Can Vuong movement.[38]

See also

- Holy Man's Rebellion (1901–1936)

- War of the Insane (1918–1921)

References

- ↑ Jonathan D. London Education in Vietnam, pg. 10 (2011): "The ultimately unsuccessful Cần Vương (Aid the King) Movement of 1885–89, for example, was coordinated by scholars such as Phan Đình Phùng, Phan Chu Trinh, Phan Bội Châu, Trần Quý Cáp and Huỳnh Thúc Kháng, who sought to restore sovereign authority to the Nguyễn throne."

- ↑ Charles Keith (2012)Catholic Vietnam: A Church from Empire to Nation, pg. 65

- ↑ Khac Vien (2013) Viet Nam: A long history, pg. 106

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 25

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 25

- ↑ Khac Vien (2013) Viet Nam: A long history, pg. 134

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 29

- ↑ Khac Vien (2013) Viet Nam: A long history, pg. 134

- ↑ Khac Vien (2013) Viet Nam: A long history, pg. 135

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 30

- ↑ Oscar Chapuis (2000) The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai, pg. 13

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 31

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 34

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 35

- ↑ Khac Vien (2013) Viet Nam: A long history, pg. 140

- ↑ Khac Vien (2013) Viet Nam: A long history, pg. 140

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 41

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 46

- ↑ Oscar Chapuis (2000) The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai, pg. 16

- ↑ Oscar Chapuis (2000) The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai, pg. 17

- ↑ Oscar Chapuis (2000) The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai, pg. 19

- ↑ Oscar Chapuis (2000) The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai, pg. 19

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 268–72

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 48

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 47

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 49-51

- ↑ Fourniau, Annam–Tonkin, pp. 39–77

- ↑ Huard, 1,017–19

- ↑ Huard, pp. 1020–23

- ↑ Huard, pp. 1096–1107; Huguet, pp. 133–223; Sarrat, pp. 271–3; Thomazi, Conquête, pp. 272–75; Histoire militaire, pp. 124–25

- ↑ Fourniau. Annam-Tonkin 1885–1896, pp. 77–79

- ↑ Thomazi. Histoire militaire, pp. 139–40

- ↑ Fourniau. Vietnam, pp. 387–90

- ↑ Oscar Chapuis (2000) The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai, pg. 93

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 68

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 76

- ↑ Oscar Chapuis (2000) The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai, pg. 94

- ↑ David Marr (1971) Vietnamese Anticolonialism, pg. 76

Sources

- Chapuis, O., The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai (2000)

- Fourniau, C., Annam–Tonkin 1885–1896: Lettrés et paysans vietnamiens face à la conquête coloniale (Paris, 1989)

- Fourniau, C., Vietnam: domination coloniale et résistance nationale (Paris, 2002)

- Huard, La guerre du Tonkin (Paris, 1887)

- Huguet, E., En colonne: souvenirs d'Extrême-Orient (Paris, 1888)

- Marr, D., Vietnamese Anticolonialism, 1885-1925 (California, 1971)

- Nguyen K.C, Vietnam: A Long History (Hanoi, 2007)

- Sarrat, L., Journal d'un marsouin au Tonkin, 1883–1886 (Paris, 1887)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l'Indochine français (Hanoi, 1931)