CII protein

| λ Phage Transcriptional Activator II | |

|---|---|

|

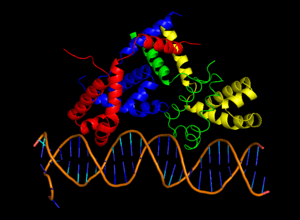

Crystal structure of λcII-DNA complex [1] | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | cII |

| PDB | 1ZPQ |

| RefSeq | NC_001416 |

| UniProt | P03042 |

cII or transcriptional activator II is a DNA-binding protein and important transcription factor in the life cycle of lambda phage.[1] It is encoded in the lambda phage genome by the 291 base pair cII gene.[2] cII plays a key role in determining whether the bacteriophage will incorporate its genome into its host and lie dormant (lysogeny), or replicate and kill the host (lysis).[3]

Introduction

cII is the central “switchman” in the lambda phage bistable genetic switch, allowing environmental and cellular conditions to factor into the decision to lysogenize or to lyse its host.[4] cII acts as a transcriptional activator of three promoters on the phage genome: pI, pRE, and pAQ.[3] cII is an unstable protein with a half-life as short as 1.5 mins at 37˚C,[5] enabling rapid fluctuations in its concentration. First isolated in 1982,[6] cII’s function in lambda’s regulatory network has been extensively studied.

Structure and properties

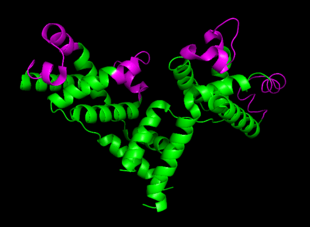

cII binds DNA as a tetramer, composed of identical 11 kDa subunits.[7] Although the cII gene encodes 97 codons, the mature cII protein subunit only contains 95 amino acids due to post-translational cleavage of the first two amino acids (fMet and Val).[6] cII is toxic to bacteria when overexpressed, as it inhibits DNA synthesis.[8]

cII binds to a homologous region 35 base pairs upstream of the promoters pI, pRE and pAQ.[7] Unlike other DNA binding proteins, cII recognizes a direct repeat sequence TTGCN6TTGC rather than sequences that form palindromes.[7] cII binds DNA ~2 orders of magnitude less strongly than the lambda repressor cI [7](3), and has a dissociation constant of ~80nM.[2] DNA binding is achieved using the common helix-turn-helix motif [1](15), located between residues 26 and 45.[7] On either side of the DNA-binding domain are domains crucial for tetramer formation, located in residues 9-25 and 46-71.[7] cII’s inherent in vivo instability stems from a C-terminal degradation tag, consisting of residues 89-97. This tag is recognized by host proteases HflA and HflB, cause rapid proteolysis cII.[9] Although the C-terminal tag is still accessible when cII is tetramerized [2] (13), the rate of proteolytic degradation decreases, since Hfl proteases only degrade cII monomers.[9]

Function

cII’s primary role in the lambda phage regulatory network is to initiate the repressor establishment cascade. Once lysogeny is established, cII is no longer needed, and thus is turned off. It serves as the switch element for establishing repression of the lytic genes after infection, producing the lysogenic phenotype.[3]

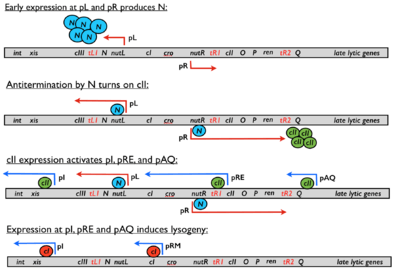

cII is first expressed after phage protein N reaches sufficient levels to antiterminate the early right transcript past tR1, allowing RNA polymerase to transcribe the cII gene.[10] If cII levels reach a certain threshold level, expression through the promoters pI, pRE and pAQ will be induced, initiating the two actions necessary in establishing lysogeny: 1) repression of lytic genes and 2) integration of the phage genome into the host’s chromosome.[11] Activation of promoter pRE enables expression of the repressor protein cI, which shuts off all lytic genes. pRE activation is also accompanied with a ~2 fold drop in pR activity due to convergent transcription of the two promoters, decreasing the expression of the lytic genes O and P.[12] Activation of promoter pAQ produces the antisense RNA for Q, a key protein in the activation of the late lytic genes. Production of antisense Q RNA shuts off Q production, reducing lytic activity until the repressor cI can adequately shut off all lytic gene expression.[13] Activation of the promoter pI causes the expression of the phage protein Int, whose role is to integrate the phage genome into the host’s chromosome.[3] Thus, although cII levels play a large role in determining the cell’s fate, random thermal fluctuations also partially determine whether lysis or lysogeny is chosen.[4]

The level of cII in the cell during infection is highly variable due to its inherent in vivo instability, and its levels are highly influenced by environmental and cellular factors that influence its degradation rate.[4] Such factors include temperature,[14] cellular starvation and number of phage infecting the cell (an indication of population number of phage).[4] Experiments have shown that low temperatures increase the in vivo half-life of cII from ~1-2 mins at 37˚C to 20 mins at 20˚C, thus increasing the probability of a cell to lysogenize. It is postulated that cII’s increased stability at lower temperatures may be due to increased tetramerization and/or decreased Hfl-protease activity.[14] Similarly, because host Hfl-proteases degrade proteins in an ATP dependent manner, coupling cII levels to Hfl-protease activity allows the bacteriophage to sense the energy status of the cell (healthy or starved).[15] Thus lysogeny is favored when cells are starved.[14] Finally, if a bacterial cell is infected by multiple bacteriophages, the level of cII increases due to additional contributions from each infecting phage. Lysogeny is therefore also favored in cells infected by multiple phages.[4]

Regulation

cII levels during infection exhibit extensive post-transcriptional regulation.

- Translation

- translation of the cII gene within the early right transcript depends on N antitermination

- cII mRNA degradation:

- The mRNA coding for the C-terminal end of cII overlaps with OOP RNA (a 77 base pair antisense RNA originating downstream of cII) by 16 codons.

- OOP hybridizes to cII mRNA, forming double stranded RNA.

- The double stranded OOP-cII RNA complex is susceptible to host RNAse III hydrolysis, destroying the cII RNA.[16]

- Host protease dependent degradation:

- C-terminal degradation tag is recognized by host HflA and HflB proteases, quickly degrading any cII they encounter.

- Tetramerization:

- oligomerization to the tetramer increases cII’s stability, allowing cII levels to accumulate at a greater rate.[9]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Jain, D.; Kim, Y.; Maxwell, K.L; Beasley, S.; Zhang, R.; Gussin, G.N.; Edwards, A.M.; Darst, S.A. (2005). "Crystal Structure of Bacteriophage λcII and Its DNA Complex". Mol. Cell. 19: 259–269. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.006. PMID 16039594.

- 1 2 3 Datta, A.B.; Roy, S.; Parrack, P. (2005). "Role of C-Terminal Residues in Oligomerization and Stability of λ cII: Implications for Lysis-Lysogeny Decision of the Phage". J. Mol. Biol. 345: 315–324. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.098. PMID 15571724.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Court, D.L.; Oppenheim, A.B.; Adhya, S.L (2007). "A New Look at Bacteriophage λ Genetic Networks". J. Bacteriol. 189 (2): 298–304. doi:10.1128/JB.01215-06. PMC 1797383

. PMID 17085553.

. PMID 17085553. - 1 2 3 4 5 Arkin, A.; Ross, A.; McAdams, H.H (1998). "Stochastic Kinetic Analysis of Developmental Pathway Bifurcation in Phage λ-Infected Escherichia coli Cells". Genetics. 149: 1633–1648. PMC 1460268

. PMID 9691025.

. PMID 9691025. - ↑ Rattray, A.; Altuvia, A.; Mahajna, G.; Oppenheim, A.B.; Gottesman, M. (1984). "Control of Bacteriophage Lambda cII Activity by Bacteriophage and Host Functions". J. Bacteriol. 159 (1): 238–242. PMC 215619

. PMID 6330032.

. PMID 6330032. - 1 2 Ho, Y.; Lewis, M.; Rosenberg, M. (1982). "Purification and Properties of a Transcriptional Activator". J. Biol. Chem. 257 (15): 9128–9134. PMID 6212585.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ho, Y.S.; Mahoney, M.E.; Wulff, D.L; Rosenberg, M. (1987). "Identification of the DNA binding domain of the phage λ cII transcriptional activator and the direct correlation of cII protein stability with its oligomeric forms". Genes Dev. 2: 184–195. doi:10.1101/gad.2.2.184. ISSN 0890-9369. PMID 2966093.

- ↑ Kedzierska, B.; Glinkowska, M.; Iwanicki, A.; Obuchowski, M.; Sojka, P.; Thomas, M.S.; Wegrzyn, G. (2003). "Toxicity of the bacteriophage λ cII gene product to Escherichia coli arises from inhibition of host cell DNA replication". Virology. 313 (2): 622–628. doi:10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00376-3. PMID 12954227.

- 1 2 3 Kobiler, O.; Koby, S.; Teff, D.; Court, D.; Oppenheim, A.B. (2002). "The phage λ cII transcriptional activator carries a C-terminal domain signaling for rapid proteolysis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (23): 14964–14969. doi:10.1073/pnas.222172499. PMC 137528

. PMID 12397182.

. PMID 12397182. - ↑ Cheng, S.C.; Court, D.L.; Friedman, D.I (1995). "Transcription Termination Signals in the nin Region of Bacteriophage Lambda: Identification of Rho-Dependent Termination Regions". Genetics. 140: 875–887. PMC 1206672

. PMID 7672588.

. PMID 7672588. - ↑ Chung, S.; Echols, H. (1977). "Positive Regulation of Integrative Recombination by the cII and cIII Genes of Bacteriophage λ". Virology. 79: 312–319. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(77)90358-0. ISSN 0042-6822. PMID 867825.

- ↑ Schmeissner, U.; Court, D.; Shimatake, H.; Rosenberg, M. (1980). "Promoter for the establishment of repressor synthesis in bacteriophage λ". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77 (6): 3191–3195. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.6.3191. PMC 349580

. PMID 6447872.

. PMID 6447872. - ↑ Ho, Y.S; Rosenberg, M. (1985). "Characterization of a Third, cII-dependent, Coordinately Activated Promoter on Phage λ Involved Lysogenic Development". J. Biol. Chem. 260 (21): 11838–11844. PMID 2931430.

- 1 2 3 Obuchowski, M.; Shotland, Y.; Kobyl, S.; Giladi, H.; Gabig, M.; Wegrzyn, G.; Oppenheim, A.B. (1997). "Stability of cII is a Key Element in the Cold Stress Response of Bacteriophage λ Infection". J. Bacteriol. 179 (19): 5989–5991. PMC 179497

. PMID 9324241.

. PMID 9324241. - ↑ Shotland, Y.; Koby, S.; Teff, D.; Mansur, N.; Oren, D.A.; Tatematsu, K.; Tomoyasu, T.; Kessel, M.; Bukau, B.; Ogura, T.; Oppenheim, A.B. (1997). "Proteolysis of the phage λ cII regulatory protein by FtsH (HflB) of Escherichia coli". Mol. Microbiol. 24 (6): 1303–1310. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4231796.x. PMID 9218777.

- ↑ Krinke, L.; Wulff, D.L. (1990). "RNase III-dependent hydrolysis of λcII-O gene mRNA mediated by λ OOP antisense RNA". Genes Dev. 4 (12A): 2223–2233. doi:10.1101/gad.4.12a.2223. ISSN 0890-9369. PMID 2148537.