Chronography of 354

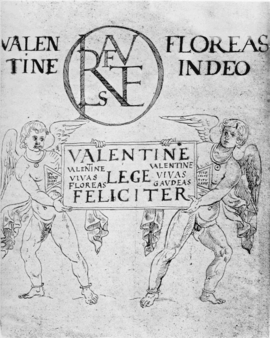

The Chronography of 354, also known as the Calendar of 354, was a 4th-century illuminated manuscript, which was produced in 354 AD for a wealthy Roman Christian named Valentinus. It is the earliest dated codex to have full page illustrations. None of the original has survived. The term Calendar of Filocalus is sometimes used to describe the whole collection, and sometimes just the sixth part, which is the Calendar itself. Other versions of the names ("Philocalus", "Codex-Calendar of 354") are occasionally used. The text and illustrations are available online.[1] Amongst other historically significant information, the work contains the earliest reference to the celebration of Christmas as a holiday or feast.

Transmission from antiquity

The original volume has not survived, but it is thought that it still existed in Carolingian times, by the 7th-8th centuries.[2] A number of copies were made at that time, with and without illustrations, which in turn were copied at the Renaissance.

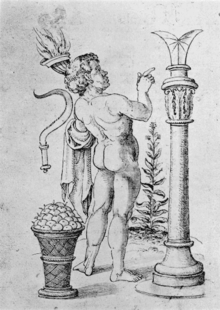

The most complete and faithful copies of the illustrations are the pen drawings in a 17th-century manuscript from the Barberini collection (Vatican Library, cod. Barberini lat. 2154). This was carefully copied, under the supervision of the great antiquary Nicholas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, from a Carolingian copy, a Codex Luxemburgensis, which was itself lost in the 17th century. These drawings, although they are twice removed from the originals, show the variety of sources that the earliest illuminators used as models for manuscript illustration, including metalwork, frescoes, and floor mosaics. The Roman originals were probably fully painted miniatures.

Various partial copies or adaptations survive from the Carolingian renaissance[3] and Renaissance periods. Botticelli adapted a figure of the city of Treberis (Trier) who grasps a bound barbarian by the hair for his painting, traditionally called Pallas and the Centaur.[4]

The Vatican Barberini manuscript, made in 1620 for Peiresc, who had the Carolingian Codex Luxemburgensis on long-term loan, is clearly the most faithful. After Peiresc's death in 1637 the manuscript disappeared. However some folios had already been lost from the Codex Luxemburgensis before Peiresc received it, and other copies have some of these. The suggestion of Carl Nordenfalk that the Codex Luxemburgensis copied by Peiresc was actually the Roman original has not been accepted.[5] Peiresc himself thought the manuscript was seven or eight hundred years old when he had it, and, though Mabillon had not yet published his De re diplomatica (1681), the first systematic work of paleography, most scholars, following Schapiro, believe Peiresc would have been able to make a correct judgement on its age. For a full list of manuscripts with copies after the originals, see the external link.

Contents

Furius Dionysius Filocalus was the leading scribe or calligrapher of the period, and possibly also executed the original miniatures. His name is on the dedication page. He was also a Christian, living in a moment that lay on the cusp between a pagan and a Christian Roman Empire.[6]

The Chronography, like all Roman calendars, is as much an almanac as a calendar; it includes various texts and lists, including elegant allegorical depictions of the months. It also includes the important Liberian Catalogue, a list of Popes, and the Calendar of Filocalus or Philocalus, also known as the Philocalian Calendar, from which copies of eleven miniatures survive. Among other information, it contains the earliest reference to Christmas (see Part 12 below) and the dates of Roman Games, with their number of chariot-races.[7]

The contents are as follows (from the Barberini Ms. unless stated). All surviving miniatures are full-page, often combined with some text in various ways:

- Part 1: title page and dedication - 1 miniature

- Part 2: images of the personifications of the cities of Rome, Alexandria, Constantinople and Trier - 4 miniatures

- Part 3: images of the emperors and the birthdays of the Caesars - 2 miniatures

- Part 4: images of the seven planets with a calendar of the hours - 5 surviving miniatures. Copies of the emblemmatic drawings appear in a Carolingian text that portrays Mercury and Venus in heliocentric orbits.[8]

- Part 5: the signs of the Zodiac - no miniatures surviving in this manuscript; four in other copies

- Part 6: the Filocalian calendar - seven miniatures of personifications of the Months in this MS; the full set appears in other copies (on December 25 "N·INVICTI·CM·XXX" - "Birthday of the unconquered, games ordered, thirty races" - is the oldest literary reference to the pagan feast of Sol Invictus. Also "VIII kal. ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeæ" "Birth of Christ in Bethlehem, Judea." is the oldest reference to Jesus birth as being on the December 25 feast day.)

- Part 7: consular portraits of the emperors - 2 miniatures (the last in the MS)

- Part 8: list (fasti) of the Roman consuls to AD 354

- Part 9: the dates of Easter from AD 312 to 411

- Part 10: list of the prefects of the city of Rome from 254 to 354 AD

- Part 11: commemoration dates of past popes from AD 255 to 352

- Part 12: commemoration dates of the martyrs, which begins with "VIII kal. Ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeae" ("Eighth day before the kalends of January [December 25], Birth of Christ in Bethlehem Judea")

- Part 13: bishops of Rome, the Liberian Catalogue

- Part 14: The 14 regions of the City

- Part 15: Chronicle of the Bible

- Part 16: Chronicle of the City of Rome (a list of rulers with short comments)

Notes

- ↑ Tertullian.org:Chronography of 354

- ↑ cf. M. Salzman

- ↑ The Leiden Aratus, a Carolingian manuscript of Phaenomena edited by Hugo Grotius in 1600, is illustrated in part with figures drawn from the Codex-Calendar of 354 (Meyer Schapiro, "The Carolingian Copy of the Calendar of 354" The Art Bulletin 22.4 (December 1940, pp. 270-272) p 270).

- ↑ A. L. Frothingham, who noted Botticelli's source, in "The Real Title of Botticelli's 'Pallas'" American Journal of Archaeology 12.4 (October 1908), pp. 438-444, reidentified the subject as Florentia and unruly civic strife.

- ↑ Nordenfalk, "Der Kalendar vom Jahre 354 und die lateinische Buchmalerei des IV. Jahrhunderts" (Göteburg) 1936, noted in Schapiro 1940:270, reprinted in Schapiro, Selected Papers: volume 3, Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art, 1980, Chatto & Windus, London, ISBN 0-7011-2514-4 On line at JSTOR

- ↑ Ramsay MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire A.D.100-400 (Yale University Press) 1984, ch. VIII "Conversions of intellectuals".

- ↑ The date of the Nativity of Jesus is given as December 25th in considerably earlier sources, but this is the first reference to a holiday or feast day being celebrated. The feast of the Epiphany had been celebrated for some time at this date.

- ↑ University of Leiden, Ms. Vossianus Q79, noted in Salzmann 1991.

References

- Weitzmann, Kurt. Late Antique and Early Christian Book Illumination. New York: George Braziller, 1977.

- Salzman, Michele Renee. On Roman Time : The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (The Transformation of the Classical Heritage 17). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Further reading

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 67, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chronography of 354. |

- Online text and images, full introduction and bibliography at Tertullian.org: Chronography of 354