Calvin C. Straub

Calvin Chester Straub FAIA (March 16, 1920 – 1998) was an American-born architect who had significant impact on architecture as both a designer and an educator. His modesty, confidence, passion for life, and no-nonsense approach resonated with a generation that, like himself, came of age in the World War II era. His influence extended through four subsequent generations as a popular professor of Architecture.

Straub was a professor of architecture at University of Southern California (1946–1961) and Arizona State University (1961–1988). As a senior partner at Buff, Smith and Hensman, he joined forces with his former students and USC alumni to produce an important body of work. The lifestyle magazine Sunset often featured his accomplishments, which were considered influential in shaping a post-World War II contemporary Southern California style [5]. His enthusiasm for architecture inspired generations of students, including Frank O. Gehry, Pierre Koenig, and many others — common among gifted and committed instructors, some reached pinnacles of success, wealth, or fame that eluded him.

Straub lived and worked at the epicentre of the evolving Southern California architecture of his day. He knew Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), Henry Mather Green (1870–1954), R.M. Schindler (1857–1953) personally, and was briefly an employee of Richard Neutra (1892–1970).[1]

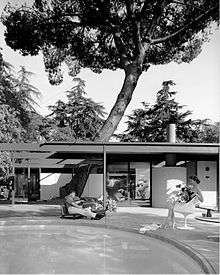

His architectural work was published extensively, usually with images by famed architectural photographer Julius Shulman. Straub is best known for his Southern California buildings, especially the approximately 30, mostly residential projects produced in his partnership with Conrad Buff III and Donald Hensman: Buff, Straub & Hensman (1956-1961). This work won numerous awards.

Straub and his contemporaries had a common culture — a comradeship born through military training and shared wartime experiences — that inspired a progressive architectural movement. The community of like-minded architects who were also military veterans included: Craig Ellwood (1922–1992), Alfred Newman Beadle (1927–1998), Gordon Drake (1917–1951), Pierre Koenig (1925–2009), Ralph Haver (1915–1987).

Biography

Born March 16, 1920, he spent his earliest years in a residence on Nob Hill in San Francisco. In 1934, the family moved to Mamaroneck, New York; in 1935, to Macon, Georgia; and in 1940, to Los Angeles and then Pasadena.

His father, Chester Straub, was a businessman who struggled with the economic impact of the Great Depression. Calvin would recall, “I have the clearest memory of my father. He had a V-12 Cadillac convertible sedan. It was chocolate brown and all the valve covers where jewel headed. He wore a black Chesterfield coat with a black homburg. It was the Depression and I don’t think he had a nickel to his name. But, he had a great car and he looked like a million bucks.” [2]

Upon high school graduation, Calvin enrolled at Pasadena Junior College, where he took courses in architecture and was active in the ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Center) program. While many of his classmates subsequently enrolled in architecture school at USC, its tuition was beyond Chester Staub's means. He could, however, afford to send his son to Texas A&M, in College Station, Texas, which he did.

Just before the war, Straub married Sylvia Gates (1920–1974), a granddaughter of William Day Gates, founder of the American Terracotta company and its arts-and-crafts line: Gates TEACO. The firm's terra cotta appears on famous Chicago works by Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright.

In the fall of 1941, Straub arrived in College Station for his university and military education. On December 7 of that year, he was in Independence, Texas, with Professor Bill Caudell and two other students looking at old regional buildings when they heard on the radio that Pearl Harbor had been attacked.[3] Straub’s draft board instructed him to return to Pasadena and wait to be drafted; he chose instead to join the V-12 Navy College Training Program, which allowed him to finish his education while awaiting deployment. In a short time, he went from being an A&M student to a graduate of USC, the school he had originally hoped to attend. He graduated as an Ensign in 1944 and reported to his ship, L.S.T. 602, in New Orleans to prepare for Europe.[4] As he later recalled, I had taken some classes in navigation, and was then handed a navigator's case with maps and instruments and told to take the ship out of port and to Europe. [5]

In 1974, Sylvia died prematurely at age 51. As her husband later said, She was my wife but also my partner in our career. We made a pretty good team for over thirty years — I still miss her. [REFERENCE NEEDED FOR THIS QUOTE] They had two daughters, Kris and Kathrin. Kathrin went on to become a successful potter and artist in the Gates family tradition. Kris had two children. After Sylvia's death, Straub seemed to lose much of his vitality, most notably in his later years.

Professorship at USC, ASU

In 1946, after his tour of duty, Straub arrived back in Pasadena, California, intent on resuming his architectural career.[6] At USC, he visited Arthur Gallion, who offered him a teaching position there At the time, USC was a hotbed of new ideas brought about by the aftermath of the war. Straub would eventually become dean of the College of Architecture. He and the school became focused on architectural responses to social issues, such as the population boom in Los Angeles and the need for low-cost housing with limited resources. "Employment in hand, Straub still faced the problem so common to millions of other returning veterans; the lack of housing ... Straub's circle of friends included a number of individuals that had never had any construction experience, but, who concluded that if they helped each other, they could solve their housing dilemma. To Straub fell the responsibly of the design of several very low-cost houses"[5]. After borrowing a set of plans as an example from Richard Neutra he began to design. He built his cottage in 1947. He developed for them a post and beam structural system. Experimenting by trial and error, the final product was lightweight, yet ridge utilizing large expanses of glass. This system was disseminated through the nation by its publication and Julius Shulman's photography. It measured 16'x24', and had been built by war-surplus materials, "the cost was $800.00 plus our own labor and bruised thumbs." said Straub. For this invention, Esther McCoy dubbed Calvin. C. Straub the "Father of California Post and Beam Architecture"

Straub's early design's were most influential in the era recognized as mid century modernism. A design vocabulary birthed in the LA Basin in the late forties through early sixties of the twentieth century. Straub became an “heir of the ‘woodsy’ Arts and Crafts tradition” being "acquainted with the modernist movement led in the west by Nuetra but initiated by Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe,” and, because of his own interests, “accepted it with enthusiasm." [7]

In his book, The Man-made Environment: An Introduction to World Architecture and Design, Straub himself refers to Arts and Crafts architecture only obliquely, focusing instead on "the small-scale buildings and houses" designed by the Bay Region architects "who were continuing to evolve forms of modern architecture in the tradition of Maybeck, Gill, and the Greene Brothers."[8] This created a synthesis of strongly divergent influences. This synthesis was informed by a principle based design philosophy rather than aesthetics or technological advancements.

"Using building materials expressive of the naturalist philosophy of the West, the design theories of the 'Arts and Crafts' Movement, and the functional traditions of the Chicago School, they carried on the development of an 'American architecture' ... Although functional in planning and concept, their designs were not overly concerned with expressing technology or mechanical functionalism as in the European 'international style'. It was more committed to humanism, the natural landscape, and the life styles of people than to abstract principles of theory." [9]

Calvin C. Straub created an artisan architecture. His designs where born of craft not technology, inspired by natural materials, informed by a personal artistic expression yet firmly committed to principles of humanism, function, responsive to the patron, context and climate; for the pleasure of use.

“Straub was committed to a humanist architecture. Like other regional modernists, he adopted a pragmatic approach, eschewing the dogmatic rigidity found in the purest forms of both the Arts and Crafts and Modernist movements. The Bay Region Style was, after all, about fusion, what Gwendolyn Wright calls “a joyful Modernism that freely mixed local vernaculars with Japanese and European influences, native redwood with industrial materials, compositional order with quirky details.” This was architecture as a means to an end, not the end itself. As architect William Wurster suggested, “Architecture is not a goal. Architecture is for life and pleasure and for people. The picture frame, and not the picture.”[10]

In 1961 Straub moved to Arizona and began teaching at Arizona State University and practising architecture in the region. His later works contributed to the development of the Sonoran Desert regional vocabulary yet maintained the same principles of his earlier work. His work was a bridge between the California art's and crafts architects and the desert modernists. He also travelled the world extensively for his World Architecture lecture course. It was attended by over 12,000 students. His travels drooped into the western architectural design vocabulary forms and world architectural influences. The Western Savings and Loan branch bank in Phoenix, Arizona reflects his inventive creativity. Straub said, "We created that roof form to hide the mechanical units, it was a smashing Idea" [1]. This project was used for his widely utilized architectural text Design Process and Communications. This roof form swept across the architectural landscape and is arguably the first use of this Polynesian inspired roof form in a modern western structure.

Statement of Intent or Manifesto

As an introduction to a retrospective exhibit of his work assembled in 1987, Straub recalled a "Statement of Intent" he wrote as a young architect in the 1950s. He felt that the ideals expressed in this youthful manifesto had retained their validity for him into the twilight of his career. A study of his works should reflect these principles again and again:[11]

• To recognize the unique nature of each client, each site, each project-there should be no preconceptions to the design

• To realize, in form, the role of architecture as a means to an end, not an end in itself. It should be an inspiring background for living, not a monument

• To create order and unity with simplicity as an antidote for the chaos and environmental anarchy of the times

• To approach architecture in a direct and honest manner-not to search for the devious and fashionable

• To understand the difference between the validity of traditions and the dead end of the cliché of eclecticism

• To participate in the total architectural process; design, construction, landscape and interiors, to bring it all together as a creative whole

• To search for refinement and self-development as opposed to sensationalism and self-indulgence

• To continue to learn through the process of observation, experimentation, and active participation in architecture. To live and to build

Summary of the characteristics of the Western House

In Straub's lecture notes prepared for a 1982 College of Architecture, Arizona State University symposium on the American House for "The Historical Development of the Western Home," one recognizes his values. These tenets are what he promoted and likely contributed through his life's work as a designer and educator of a unique form of American Architecture.

They also summarize much of the work promoted in that era through Sunset Magazine, and many other western publications, including Arts and Architecture and its case study program that made Straub and others famous.

• There is a concern for the "Total Environment"- the integration of House, Site, and landscaped structure into a unified whole that is harmonious with the Natural Environment.

• These houses are more concerned with the human experience within the house rather than with a pre-occupation with the external appearances.

• The Western House is more concerned with creating a background for people rather than a dominating formal statement. Criteria are; serenity, unobtrusiveness and avoidance of self-conscious pretentiousness.

• The use of simple natural material and expressed structure appropriate to climate, function and site.

• Planning is open and fluid-both horizontally and vertically., but still respects and celebrates the biological realities of family life and privacy.

• In general the absence of formality reflects the traditional western informal way of living.

• To Summarize- the Western House is a natural house, more concerned with the well being of the people than with formalism, closely involved with the natural environment, and philosophically dedicated to "The good life".

These observations by Calvin C. Straub on the western home perhaps most clearly define his work, his contribution to architecture and that of those contemporaries who shared similar principles. Those Cal Straub and his comrades would have defined as "one of us." [1]

Projects

- 1946 Calvin Straub "Cottage," Altadena, CA

- 1947 Kenneth Brown "Cottage," Sierra Madre, CA

- 1948 Hugh Gates House, Pasadena, CA

- 1949 Paul Caler Residence, West La Cañada, CA

- 1950 Henry Hoag Residence, Pasadena, CA

- 1951 Richard Sedlacheck Residence, Laurel Canyon Los Angeles

- 1951 Frank McCauley Residence, Bel Air, Los Angeles, CA

- 1952 Calvin Straub Residence, Altadena, CA

- 1952 Virginia Fischer Residence, Mandeville Canyon, CA

- 1953 Milton Farstein Residence, Pacific Palisades, CA

- 1953 George Brandwo Residence, San Marino, CA

- 1953 William Robertson Residence, Altadena, CA

- 1953 W. Brace Residence, Altadena, CA

- 1954 C. Mello Residence, Pasadena, CA

- 1954 Richard Frank Residence, Pasadena, CA

- 1954 Holland Residence, Pasadena, CA

- 1954/1988 Lawry's California Center Office Bldg, Sales & Garden, Los Angeles

- 1955 Idyllwild School of Music and Arts (USC) (Administration Bldg, Theater & Class Studios), Idyllwild, CA

- 1955 Dr. W. Thompson Residence, Pasadena, CA

- 1956 Jack Thompson Residence, Pasadena, CA

- 1956 D. Edwards Residence, Beverly Hills, CA

- 1956/57 Dr. J. Shields Residence, Pacific Palisades, CA

- 1957 Van de Kamp Residence, Beverly Hills, CA

- 1957 Tom Hubble Residence, Laguna Beach, CA

- 1958 Saul Bass Residence (Case Study House #20), Altadena

- 1958 Dr. S. Fine Residence, Pacific Palisades, CA

- 1958 H. Gates Residence #2, Pasadena, CA

- 1958 Tom Wirick Residence, Pasadena, CA

- 1959 Frank Residence, Pasadena

- 1959/60 Donald Simon Residence, Whittier, CA

- 1960 W. Taylor Residence, Sierra Madre, CA

- 1961 John Thomson Residence

- 1962 Sidney Fine Residence

- 1962 Residence for Mr. Steve McQueen, Los Angeles

- 1963 Residence for Mr & Mrs Marcus Whiffen, Phoenix, AZ

- 1963 Harry Roth Residence, Beverly Hills

- Penn/Walter Van der Kamp Residence, Los Angeles

- 1965 Case Study House #28

- 1965 Lawry's Des Plains Office & Manufacturing Center Des Plains, IL (master plan and offices)

- 1965/66 Carter Norris Residence, Paradise Valley, AZ

- 1966/67 R. Andeen Residence, Paradise Valley, AZ

- 1967 M.C. Gill Residence, Pasadena

- 1968 Renovation for Judge Sandra Day O'Connor, Phoenix, AZ

- 1970 C. Cummings Residence, Mesa, AZ

- 1970 Western Savings & Loan branch bank, Phoenix, AZ

- 1974 Western Savings & Loan branch bank, Scottsdale, AZ

- 1975 C. Butler Residence, Paradise Valley, AZ

- 1975 J. Ellewood Residence, Scottsdale, AZ

- 1975 Prescott Public Library, Prescott, AZ

- 1980 P. Bidstrup Residence, Paradise Valley, AZ

- 1980 Scottsdale Festival Center Park & Flood Control, Scottsdale, AZ

- 1985 Frank Dining Hall (Pomona College), Pomona, CA

- 1985 Dr. Danto Residence, Scottsdale, AZ

- 1988 Robert Ellis Residence, Scottsdale, AZ

- 1993 Dennis & Kathrin Straub Parsons Residence, Kenwood, CA (Wm. Mark Parry, associate)

References

1. Recollections from notes and conversations between Calvin C. Straub and Wm. Mark Parry; Parry was Straub's last associate. (1991–1998)

2. Hensman, D.C. and J. Steele, Buff & Hensman. 2004, Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California Guild Press.

3. "A Personal History of the Straub Family During the Last Hundred Years", by Calvin C. Struab, 1996.

4. Ibid.

5. Richard A. Eribes in "The California Houses of Calvin C. Straub: A Modern Crafts Legacy". Unpublished manuscript.

6. Interviews with Calvin Straub by Richard A. Eribes in “The California Houses of Calvin C. Straub: A Modern Crafts Legacy". Unpublished manuscript partially funded by a grant from the Graham Foundation

7. Winter, R., Toward a Simpler Way of Life: The arts & crafts architects of California. 1997, Berkeley: University of California Press. 310 p.

8. Winter, R., Toward a Simpler Way of Life: The arts & crafts architects of California. 1997, Berkeley: University of California Press. 310 p.

9. Straub, C.C., The Man-made Environment: An Introduction to World Architecture and Design. Prelim. ed. 1983, Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt.

10. Wolf Peter j. Regional Modernism for the Desert:Calvin Straub's Arizona Architecture. modernphoenix.net 2009