Carbonear

| Carbonear | ||

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

|

Carbonear Old Post Office | ||

| ||

| Motto: "As Loved Our Fathers" | ||

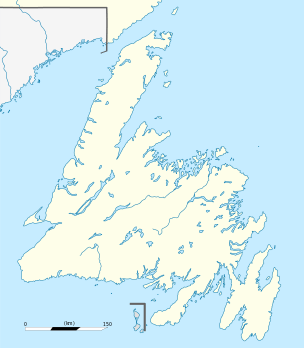

Carbonear Location of Carbonear in Newfoundland | ||

| Coordinates: 47°44′15″N 53°13′46″W / 47.73750°N 53.22944°WCoordinates: 47°44′15″N 53°13′46″W / 47.73750°N 53.22944°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| Province |

| |

| Settled | 1631 | |

| Incorporated (town) | 1948 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | George Butt, Jr.[1] | |

| • Deputy Mayor | Frank Butt[2] | |

| • MLA | Steve Crocker | |

| • MP | Scott Andrews | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 11.81 km2 (4.56 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 34 m (112 ft) | |

| Population (2011) | ||

| • Total | 4,739 | |

| • Density | 399.8/km2 (1,035/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | Newfoundland Time (UTC-3:30) | |

| • Summer (DST) | Newfoundland Daylight (UTC-2:30) | |

| Postal code span | A1Y | |

| Area code(s) | 709 | |

| Highways | Route 70 | |

| Website |

www | |

Carbonear is a town in the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. It overlooks the west side of Conception Bay and had a history long tied to fishing and shipbuilding. Since the late 20th century, its economy has changed to emphasize education, health care and retail. There were 4,739 people living in Carbonear in 2011; this is up from 4,723 in 2006.[3]

History

The town of Carbonear is one of the oldest permanent settlements in Newfoundland and among the oldest European settlements in North America. The harbour appears on early Portuguese maps as early as the late 1500s as Cabo Carvoeiro (later anglicized as Cape Carviero). There are a number of different theories about the origin of the town's name. Possibly from the Spanish word "carbonera" (charcoal kiln); Carbonera, a town near Venice, Italy where John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) had been resident; or from a number of French words, most likely "Charbonnier" or "Carbonnier".

In the late 20th century, historian Alwyn Ruddock of the University of London, one of the world's foremost experts on John Cabot's expeditions to the New World, suggested that a group of reformed Augustinian friars, led by the high-ranking Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis, accompanied Cabot on his second voyage to reach North America in 1498. (Italian bankers had helped finance Cabot's previous expeditions.) The friars stayed to establish a mission community in Newfoundland for the Augustinian order of the Carbonara. She believed that the settlement may have been short-lived but built a church. The modern name of the town may be derived from the order and its church. If true, Carbonear would have been the first Christian settlement of any kind in North America, and the site of the oldest, and only, medieval church built on the continent.[4] Evan Jones of the University of Bristol is leading further investigations of Dr Ruddock's claims to find additional evidence with colleagues in what is known as The Cabot Project.[5]

By the time the British began permanent colonization of the island in the early 17th century, the name Carbonear was already being used by the seasonal fishermen familiar with the area. Most of the area's land had been granted to Sir Percival Willoughby. One of Carbonear's first residents was Nicholas Guy, co-founder of the first British colony in Canada at Cuper's Cove (now Cupids), founder of the Bristol's Hope Colony (now Harbour Grace), and father of the first English child born in Canada. He moved there from the other colonies by no later 1631 to fish and farm the land with his family in an agreement with Willoughby. The Guy family continued as the predominant planter family in Carbonear throughout the 17th century.

At about this time legend tells of an Irish princess of the O'Conner family, Sheila NaGeira, who settled in Carbonear after being rescued by privateer Peter Easton and marrying his first officer Gilbert Pike. Much is known about Easton and his exploits, but evidence of NaGeira has yet to be found. The legend's combination of romance, pirates, and New World adventure has inspired much research and numerous works of fiction on the topic.

By the late 17th century, unlike many settlements in Newfoundland from this period where men outnumbered the women by a ratio of ten to one, Carbonear was a true community with families, and many women and children to help develop the town's prosperity. It became a target for England's enemies, and privateers. When war broke out with France, Carbonear was attacked by French captain Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville during the Avalon Peninsula Campaign. The citizens survived by retreating to the fortified Carbonear Island, but the town, documented by the French as being "very well-established" and containing properties that were "the best-built in all of Newfoundland", was burned to the ground. During four months of raids, Iberville was responsible for the destruction of thirty-six Newfoundland settlements. By the end of March 1697, only Bonavista and Carbonear Island remained in English hands.

Over the next hundred years, Carbonear was attacked and burned two more times by the French in their attempts to control Newfoundland, and then later by American privateers. The residents continued to improve the fortifications using their own money and although the town was repeatedly burned, Carbonear Island protected its residents. The town developed as one of the most important in Newfoundland in this period. When Judiciary districts were set up to govern the island in 1729 by Commodore Governor Henry Osborn, Carbonear was recognized and was chosen as one of the six initial districts. With new French threats, the British finally erected a fort and garrison on the Island in 1743. During the Seven Years' War, the French invaded and gained control of the fort, burning its buildings and tossing the cannons over the cliffs in 1762. They can still be seen on the beach below.

The Archaeology of Historic Carbonear Project, carried out by Memorial University of Newfoundland, has conducted summer fieldwork each season since 2011 in the town to reveal its colonial history. So far, it has found evidence of planter habitation since the late 17th century and of trade with Spain through Bilbao, including a Spanish coin minted in Peru. It has found evidence of other settlement through the 19th century.[6][7] The first summer's work uncovered approximately 1300 artifacts. The Carbonear Heritage Society is developing an interpretive museum exhibit for these and future finds.

With the rise of the seal hunt and the Labrador cod fishery, Carbonear became a major commercial centre in the 19th century. More sea captains came from Carbonear for the foreign fishing trade than from any other Newfoundland outport in this era. Violent political riots here in the early and mid-19th century led to the dissolution of the Newfoundland Legislature in 1841 and the suspension of the constitution. Political riots were so common here during this period, especially during elections, that the term Carbonearism was coined to describe the behaviour.[8] Rail service began in 1898 (with a 1st class ticket to St. John's costing $2) and expanded with a new rail station in 1917. It operated until the closure of the rail line in 1984.

In the late 20th century, the economy was forced to diversify. The seal hunt and the Labrador fishery had almost disappeared. Carbonear's importance as a shipbuilding centre and international port of trade had much declined. Fish processing continued to be the primary industry until the collapse of the cod fishery in the early 1990s. The fish processing plant has been converted to process crab and most recently seal. To counter these changes, Carbonear is evolving. With two college campuses, a shopping centre, a major hospital, and three long-term care facilities, the town has built on its importance as a regional retail, service, transportation, government, and cultural centre, earning it the nickname "Hub of the Bay".

Timeline

- 1630s - 1640s - Mary Weymouth is listed as running a plantation in Carbonear.

- 1631 - Nicholas Guy, formerly of Cupids, is settled at Carbonear with his family.

- 1675 - Census records 11 permanent residents, 16 children, 8 boats, and 30 servants living year round in Carbonear.

- 1679 – William Downing and Thomas Oxford propose to fortify "Carboniere" on behalf of the residents.

- 1697 – The settlement consisting of 22 houses is destroyed by the French. The French report that the houses are "the best built in all Newfoundland". Carbonear Island was used for defense.

- 1705 – The French burned the town. Residents defended themselves on Carbonear Island.

- 1729 - Carbonear is designated one of the six Judiciary districts in Newfoundland. Two of the first Justices of the Peace, William Pinn and Charles Garland are assigned to the district.

- 1743 - British build a fort on Carbonear Island and garrison it with troops.

- 1755 - Roman Catholics convicted for saying the Mass and having confession. Magistrates ordered to suppress RC services and to exile priests.

- 1762 - Successful invasion of Carbonear Island by the French during the Seven Years' War. Fort burned.

- 1767 – The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel establish an Anglican church at Carbonear.

- 1775 – Carbonear attacked by American privateers.

- 1788 – The first Methodist church in Carbonear is erected, the largest of this denomination in Newfoundland.

- 1812 - Cannon erected on Harbour Rock Hill to protect against American attacks.

- 1816 - Stores looted by mobs

- 1826 – Newfoundland School Society is established in Carbonear and has 100 students.

- 1826 - First Catholic church built and dedicated to St. Patrick. A Catholic parish had existed since 1784.

- 1832 - Sealers' strikes and riots.

- 1835 - Newspaper journalist Henry Winton attacked on Saddle Hill and had his ears cut off over religious comments.

- 1836 - Gut Bridge built linking Carbonear's North and South sides.

- 1840 - Political riots lead to the dissolution of the Legislature and the suspension of the constitution.

- 1841 - Volunteer Fire Department established.

- 1852 - Telegraph line to St. John's becomes operational.

- 1859 - Fire destroys much of Carbonear.

- 1861 - One man killed in riots.

- 1862 – Hungry mobs dressed as mummers loot the streets in what is known as The Winter of the Rals or The Mummers' Riot. Troops from the St John’s garrison are sent to restore order.

- 1864 - St. James' Anglican Church completed

- 1866 – The Grammar School (established in 1838) is closed; students are divided between Roman Catholic and Protestant boards equally.

- 1870 - Rorke Stores built on Water Street and quickly become the unofficial commercial centre of the town.

- 1891 - St. Patrick's Catholic church completed. Previous chapel converted to a convent.

- 1898 - Rail line to Carbonear completed with twice-daily service.

- 1905 - New Post Office built on Water St to replace one destroyed by fire the previous year. Monument erected to heroine Tryphoena Nicholl, postmistress who died in saving other people trapped inside the burning building.

- 1908 - United Church College is built.

- 1917 - Train station expanded due to increased traffic and rail line extension to Bay de Verde.

- 1932 - 100 policemen brought by train to restore order in Carbonear due to riots during the Great Depression.

- 1948 - Incorporated into a town with elected government.

- 1949 - Bond Theatre opens 1 April 1949 showing The Razor's Edge. Built partially from materials recovered from a German POW camp in nearby Victoria Village.

- 1957 - Larger modern post office building opens.

- 1961 - United Church Regional High School opens. Renamed to James Moore Regional High in 1967, then James Moore Central High in 1974.

- 1964 - Alfred Penney Memorial Hall (elementary school) is destroyed by fire.

- 1965 - Davis Elementary School opens.

- 1968 - The Compass newspaper starts publication.

- 1976 – Official opening of the new Regional Hospital takes place; the old hospital is converted to a nursing home for elderly patients.

- 1978 – Trinity Conception Square shopping mall is opened.

- 1984 - End of rail service to Carbonear.

- 1985 - James Moore Central High School closes; Carbonear Integrated Collegiate opens.

- 1997 - St. Clare's School is closed.

- 1998 - Princess Sheila NaGeira Theatre and the Conception Bay Regional Community Centre are opened.

- 2004 - St. Joseph's School closes.

- 2011 - Carbonear Cinemas is closed as a result of a fire after the screening of a film on October 24.

- 2013 - Davis Elementary School closes.

- 2013 - Carbonear Academy opens.

- 2014 - The Bond Theatre building burns down.

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Education

- Carbonear Academy - Kindergarten to grade 8

- Carbonear Collegiate - Grades 9, 10, 11, and 12

- College of the North Atlantic - Post-secondary

- Keyin College - Post-secondary

Sports and community life

- Carbonear swimming pool

- Carbonear Recreation Complex - includes 4 tennis courts, 2 baseball diamonds, Track and field, Soccer, and basketball court.

- Three community playgrounds

- Community boardwalk and walking trails

- Public Library

- Princess Sheila NaGeira Theatre

- Trinity Conception Square - the regional shopping mall

Health

- Carbonear General Hospital

- Harbour Lodge Nursing Home

- Interfaith Citizens Home

Media

- The Compass - local newspaper (www.cbncompass.ca)

- KIXX Country - 103.9 FM local radio station

Tourism

- Carbonear Walking Tours - Historical walking tours leaving from the Railway Museum

- Island Charter Tours - Boat tours of Carbonear Island; scuba

- Rorke Store Museum

- Railway Museum

- Old Post Office & Heritage Society

- Princess Sheila NaGeira Theatre

- Earle's Riding Horses

Festivals and events

- Kiwanis Music Festival

- Conception Bay Folk Festival (now defunct)

- Carbonear Good Old Opry - June 5, 2014

- Canada Day Concert @ Paddy's Garden - June 28, 2014

- Celtic Roots Folk Festival - July 12, 2014

- Relic Riders Show 'N' Shine - July 25–27, 2014

- Carbonear Day Parade - Aug 1

- Christmas Winter Lights and Santa Claus Parade - December

- Remembrance Day Parade - Nov 11

Notable people born/lived at Carbonear

- Duane Andrews (musician)

- Robert William Boyle (physicist/inventor of sonar)

- Davis Earle (nuclear physicist)

- Philip Henry Gosse (marine biologist)

- Jerome Kennedy (politician)

- Séan McCann (musician Great Big Sea)

- Frank Moores (Newfoundland Premier)

- Rex Murphy (noted commentator)

- Princess Sheila NaGeira

- Augustus Rowe (politician and physician)[9]

References

- Tocque, Philip (1878). Newfoundland: as it was, and as it is in 1877. S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington. p. 511.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-31. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-31. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ↑ Population and dwelling counts

- ↑ Evan T. Jones (2008), "Alwyn Ruddock: John Cabot and the Discovery of America ", first published online 5 April 2007, Historical Research, Volume 81, Issue 212, May 2008, pp. 242–9.

- ↑ "The Cabot Project", University of Bristol, 2009

- ↑ Peter E. Pope and Bryn Tapper, "Historic Carbonear, Summer 2013", Provincial Archaeology Office 2013 Archaeology Review, Vol. 12-2013, accessed 24 April 2015

- ↑ Mark Rendell, "17th-century coins unearthed in Carbonear", The Telegram, 17 April 2014, accessed 24 April 2015

- ↑ PANL, Newfoundland, Executive Council, Minutes, 1 March 1862. Newfoundland, Blue Books, 1842–74 (copies in PANL); House of Assembly, Journals, 1863, 8, 931. Courier (St John’s), 20 March, 25, 29 Oct. 1862. Newfoundlander (St John’s), 18 Oct. 1872, 17 Jan. 1873, 26 Feb. 1875. Newfoundland Patriot (St John’s), 27 Feb 1875. Pilot (St John’s), 8, 22 Jan. 1853. Public Ledger (St John’s), 30 Oct., 14 Nov., 15 Dec. 1840; 28 Jan. 1862. Record (St John’s), 8 March 1862, 15 Dec. 1863. Times and General Commercial Gazette (St John’s), 4 Jan. 1843. E. A. Wells, “The struggle for responsible government in Newfoundland, 1846–1855,” unpublished MA thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1966.

- ↑ Robinson, Andrew (2013-07-23). "Former N.L. health minister dead at 92". The Telegram. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carbonear. |