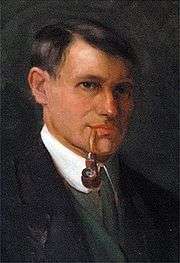

Casimir Markievicz

Casimir Dunin Markievicz (Polish: Kazimierz Dunin-Markiewicz [kaˈʑimʲɛʂ ˈdunin markˈjɛvit͡ʂ], 15 March 1874 – 2 December 1932), known as Count Markievicz, was a Polish portrait, category and landscape artist, playwright and theatre director, and husband of the Irish revolutionary Constance Markievicz.

Biography

The Dunin Markievicz family held land in Ukraine, and had an estate at Zywotowka (Polish: Żywotówka) where Casimir grew up.[1] Markievicz attended the State Gymnasium in Kherson, and studied law at the University of Kyiv.[1] In 1895 he transferred to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. While in Paris, he met and married Jadwiga Splawa-Neyman. They had two sons, Stanislas and Ryszard, but the marriage did not last. Jadwiga returned to Ukraine where she and Ryszard died in 1899.[2] He met Constance Gore-Booth in 1899, and the two mixed in the bohemian Paris society of the time. In Paris, Markievicz was known as "Count Markievicz". When Constance's family enquired as to the validity of the title, they were informed through Pyotr Rachkovsky of the Russian Secret Police that he had taken the title "without right", and that there had never been a "Count Markievicz" in Poland.[3] (An online list of counts of the imperial Russian nobility does not include anybody by the name of Markiewicz.)[4] However, the Department of Genealogy in Saint Petersburg said that he was entitled to claim to be a member of the nobility.[5] Markievicz and Gore-Booth married in London in 1900, and their daughter, Maeve, was born the following year.[6] From 1902 the couple lived in Dublin. He continued to be known as "Count Markievicz" (and Constance as "Countess Markievicz"), and in the 1911 census gave his occupation as "Count (Russian nobility)".[7] Stanislas later said in a letter that his father had not been a count.[8]

Markievicz was part of the literary circle that centred on W. B. Yeats and the Abbey Theatre. In 1910 he formed his own theatre company, the Independent Dramatic Company, which staged plays written by himself and starring his wife, Constance.[9] In 1913 Markievicz moved to present-day Ukraine, and never returned to live in Ireland. However, he did correspond with his wife in Dublin and he was by her side when she died in 1927.

Towards the end of his life Markievicz was active in Warsaw, as well as a correspondent for English magazines, such as the Londoner Daily News. He also wrote the screenplay of a 1920 Polish film, Powrót, directed by Aleksander Hertz.[10] The largest part of his art collection is held in Dublin, some remain in Poland (National Museum, Kraków and in private collections). His talent lent itself particularly to the large oil portraits of Polish presidents Piłsudski[11] and Wojciechowski.[12] A catalogue for his works is still pending.

He died in Warsaw, Poland, in 1932.[10]

Plays

(Source: Productions of the Irish Theatre Movement, 1899-1916)[13]

- Seymour's Redemption, Abbey Theatre, 9 March 1908

- The Dilettante, Abbey Theatre, 3 December 1908

- Home Sweet Home (with Nora Fitzpatrick), Abbey Theatre, 3 December 1908

- The Memory of the Dead, Abbey Theatre, 14 April 1910

- Mary, Abbey Theatre, 14 April 1910

- Rival Stars, Gaiety Theatre, 11 December 1911

References

- 1 2 Haverty, Anne (1988). Constance Markievicz: Irish Revolutionary. London: Pandora. p. 48. ISBN 0-86358-161-7.

- ↑ Ryan-Smolin, Wanda (1995). "Casimir Dunin Markievicz, Painter and Playwright". Irish Arts Review Yearbook. 11: 180. JSTOR 20492833. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Arrington, Lauren (2015). Revolutionary Lives: Constance and Casimir Markievicz. Princeton University Press. pp. 21–2. ISBN 1400874181. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ List of Counts of the Russian Empire at russiannobility.org

- ↑ Arrington (2015), p. 22 (footnote)

- ↑ S. Pašeta, "Markievicz , Constance Georgine, Countess Markievicz in the Polish nobility (1868–1927)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 29 September 2007.

- ↑ 1911 census return

- ↑ Nevin, Donal (2005). James Connolly: "A Full Life". p. 589. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ Morash, Chris (2002). A History of Irish Theatre, 1601-2000. Cambridge University Press. p. 152. ISBN 0-521-66051-3. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- 1 2 Casimir Markievicz at the Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "Portret Piłsudskiego już odnowiony". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). 19 July 2002. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Historia i społeczeństwo: Ojczysty panteon i ojczyste spory. Do nowej podstawy programowaj, liceum i technikum, podrecznik (in Polish). p. 186. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ O'Ceallaigh Ritschel, Nelson (2001). Productions of the Irish Theatre Movement, 1899-1916: A Checklist. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 39, 44, 58, 59, 67, 72, 74. ISBN 0-313-31744-5. Retrieved 13 August 2011.