Cauldron (video game)

| Cauldron | |

|---|---|

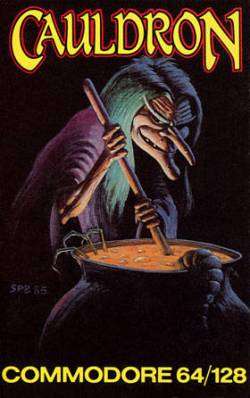

The box art depicts the main protagonist, a witch. Artwork by Steve Brown. | |

| Developer(s) | Palace Software |

| Publisher(s) | Palace Software |

| Designer(s) | Steve Brown |

| Programmer(s) | Richard Leinfellner |

| Composer(s) | Keith Miller |

| Platform(s) | Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, Enterprise 128 |

| Release date(s) | 1985 |

| Genre(s) | Arcade adventure, platform game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Cauldron is a two-dimensional (2D) shoot 'em up/platformer computer game developed and published by British developer Palace Software (Palace). The game was released in 1985 for the ZX Spectrum, Commodore 64 and Amstrad CPC home computers. Players control a witch, who aims to become the "Witch Queen" by defeating an enemy called the "Pumpking".

Designed by Steve Brown and Richard Leinfellner, Cauldron originated as a licensed video game of the horror film Halloween. Brown eventually altered the game to use a theme based on the Halloween holiday. The mix of two genres resulted from Brown and Leinfellner wanting to make a shoot 'em up and platform game, respectively. The developers realized that there were no technical limitations preventing the genres from being combined.

The game received praise from video game magazines, who focused on the graphics and two different modes of play. A common complaint was Cauldron's excessive difficulty. The following year, Palace released a direct sequel titled Cauldron II: The Pumpkin Strikes Back.

Gameplay

Players navigate the witch protagonist through the 2D game world from a side-view perspective. Cauldron is divided into two modes of play: shooting while flying and jumping along platforms. Areas of the game world set on the surface feature the witch flying on a broom stick, while underground segments require the witch to run and jump in caverns. In the flying segments, players must search for four randomly scattered coloured keys to access underground areas that contain six ingredients. The objective is to collect the ingredients and return them to the witch's cottage to complete a spell that can defeat the Pumpking. While traversing the game world, the witch encounters Halloween-themed enemies such as pumpkins, ghosts, skulls, and bats, as well as other creatures like sharks and seagulls. A collision with an enemy causes the witch's magic meter (which is also used to fire offensive projectiles at enemies) to decrease. The character dies once the meter is depleted. After dying, the character reappears on the screen and the meter is refilled. Players are given limited opportunities for this to occur, and the game ends once the number of lives reaches zero.[1][2][3][4]

Development

Cauldron began development as a game based on the 1978 film Halloween. Palace obtained the video game rights and assigned Steve Brown to the project. Unable to develop a concept he was happy with, Brown took the game in a new direction. Inspired by the Halloween holiday, he envisioned a game featuring witches and pumpkins.[1] Stuart Hunt of Retro Gamer, however, attributed the switch to Mary Whitehouse's campaign against so-called 'video nasties' in the 1980s.[5]

Brown submitted concept drawings to Palace co-founder Pete Stone, who approved further development. Influenced by what he deemed a "classical witch", Brown designed the witch with a long nose and a broomstick. He created a Plasticine model of the character as a reference for a painting that was used for the game's box art. Brown was joined by Richard Leinfellner, who served as the lead programmer. The two enjoyed different video game genres—Brown liked platform games, while Leinfellner preferred shoot 'em ups—and decided to create a game engine that could handle both methods of playing. Both developers play tested the game, but only played the segments individually rather than in a sequence. In retrospect, Brown attributes the game's excess difficulty to this along with the fact that the two played with unlimited game lives.[1] The game was released on three home computers: Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64, and ZX Spectrum.[6] The Spectrum and Amstrad versions lack scrolling graphics in the shoot 'em up levels and use flick-screening to approximate it.[1][7] A port of Palace's 1984 game The Evil Dead, originally programmed for the Commodore 64 by Leinfellner, was included on the second side of the Spectrum cassette.[2][4][8] Retailers feared a parental backlash, resulting a limited release for the game. Palace chose to include The Evil Dead to distribute the game to a wider audience.[5]

Reception and legacy

| Reception | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

The game was well received by the video game press, who focused on the graphical quality and game design. Computer and Video Games described the game as a "quality arcade-adventure" and called the graphics stunning.[4] Reviewers from Crash magazine praised the animation and detail of the graphics, as well as the gameplay.[7] Three of Zzap!64's reviewers—Julian Rignall, Bob Wade, and Gary Penn—echoed similar statements about the graphics. The group complimented the gameplay, specifically the adventure aspects, and considered the large game world a positive component.[3] A Computer Gamer reviewer praised the flying portions of the game, calling the gameplay enjoyable. While he praised the platforming portions, the reviewer commented that design flaws made the game more difficult than it should have been.[8] Clare Edgeley of Sinclair User praised the graphical quality of the ZX Spectrum version, but commented that the colors occasionally overlap and the screen flickers.[2] ZX Computing's reviewer praised the ZX Spectrum conversion, calling it superior to the Commodore 64 release. The reviewer lauded the graphics and gameplay of the flying segments, but bemoaned the platforming aspect and described it as a Jet Set Willy clone.[9]

Publications dedicated to the ZX Spectrum platform considered the inclusion of The Evil Dead with the ZX Spectrum release a positive aspect that added value to the overall package.[2][7][9] The game's difficulty was a common complaint. Computer Gamer, Crash, and ZX Computing commented that playing the game with limited lives was very challenging.[7][8][9] Retro Gamer's Craig Grannell described the game as "unforgiving", citing difficulty landing and excessive precision required in the flying and platforming segments respectively. Following the success of Cauldron, Palace released a direct sequel, Cauldron II: The Pumpkin Strikes Back, in 1986. The game is set after the events of the first game, and features a bouncing pumpkin that survived the witch's ascension to power. Players navigate the pumpkin around a castle in search of the Witch Queen to enact revenge.[1] Cauldron was later re-released along with its sequel as a compilation title on Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum computers.[10][11] The commercial success of the two Cauldron games prompted Palace to give Brown more creative freedom for his following project, Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grannell, Craig. "The Making of Cauldron and Cauldron II". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (35): 48–51.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Edgeley, Clare (July 1985). "Spectrum Software Scene: Cauldron". Sinclair User. EMAP (40): 22.

- 1 2 "Cauldron". Zzap!64. Newsfield Publications (1): 110–111. May 1985.

- 1 2 3 Takoushi, Tony (April 1985). "Hot Gossip". Computer and Video Games. EMAP (42): 16.

- 1 2 Hunt, Stuart. "The History of Videogame Nasties". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (57): 48.

- ↑ "Cauldron". MobyGames. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Cauldron". Crash. Newsfield Publications (18): 34. July 1985.

- 1 2 3 CJ (August 1985). "Reviews: Cauldron". Computer Gamer. Argus Specialist Publications (5): 67.

- 1 2 3 4 "Review: Cauldron". ZX Computing. Argus Specialist Publications: 78–79. August–September 1985.

- ↑ Pelley, Rich; Pillar, Jon (February 1991). "Bargain Basement: Cauldron I & II". Your Sinclair. Dennis Publishing (62): 52.

- ↑ "Cauldron I & II Tech Info". GameSpot. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ Carroll, Martyn (30 March 2006). "Company Profile: Palace Software". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing (23): 66–69.