Charles Francis Murphy

| Charles Francis Murphy | |

|---|---|

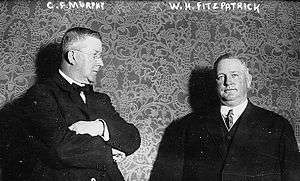

Charles F. Murphy, ca. 1903. | |

| Born |

Charles Francis Murphy June 20, 1858 New York City, New York |

| Died |

April 25, 1924 (aged 65) New York City, New York |

| Nationality | Irish-American[1] |

| Occupation | Politician[1] |

Charles Francis "Silent Charlie" Murphy (June 20, 1858 – April 25, 1924), also known as Boss Murphy, was an American political figure, Head of New York City's Tammany Hall from 1902–1924. Murphy was responsible for transforming Tammany Hall's image from one of corruption to respectability, as well as extending Tammany Hall's political influence to the national level.[1]

Early life

Murphy was the son of Irish immigrants Dennis Murphy and Mary Prendergrass.[1] He quit school at age 14 and found a job at Roaches Shipyard, and eventually as a driver for the Crosstown Blue Lines Horsecar Co. After saving $500 from the jobs that he had worked, Murphy purchased a saloon in 1878, which he named Charlie's Place.[1] Charlie's Place became a local gathering place for local workers, but did not serve women.[1] The second floor of the Saloon served as the Sylvan Social Club, composed of men, aged 15 to 20.[2] With this social club, Murphy formed a baseball team and with all three groups, Murphy arose as a local political figure.

Political career

Murphy's friend and benefactor, Edward Hagan failed to achieve the Tammany Hall nomination for district assemblyman in 1883, which led Hagan to attempt an independent campaign.[2] Murphy managed Hagan's independent campaign, leading to Hagan's victory.[1] Murphy was also prominent in Francis Spinola's successful campaign for US Congress in 1885. That same year, one of Murphy’s saloons became the headquarters for the Anawanda Club, which was the local Tammany Hall club; eventually Murphy joined Tammany Hall's Executive Committee.[1] Murphy was appointed to be the Commissioner of Docks in 1897.[1] During this period, he organized the New York Contracting and Trucking Company, which leased dock space.[1] This became a successful business and Murphy gained further prominence in Tammany Hall. In 1902, Murphy married Margaret J. Graham; also that year, the then-current Tammany Hall boss, Richard Croker, was forced out of office due to public accusations of corruption.[1] The accusations of corruption included stealing from the municipal treasury, which never occurred.[3] Murphy quickly replaced Croker as Boss of Tammany Hall.[1]

In contrast to Croker, the taciturn and teetotaling Murphy brought an air of respectability to Tammany Hall. He furthered this end by promoting a new crop of Tammany politicians—chief among them Senator James J. Walker, Rockland County Chairman James Farley, and Alderman Alfred E. Smith—who would move the machine away from the methods of Boss Tweed and toward a Progressive Era-style that rewarded the loyalty of the poor with reforms like factory safety and child labor laws. Although initially opposed to progressive legislation, Murphy realized that he could support reforms which pleased his constituency but which did not undermine Tammany's power.[4] Because of this stance, he is credited with transforming Tammany into a political organization capable of drawing the votes of the ever-growing numbers of new immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, which kept Tammany in power until the early 1930s.

Political Influence

During his reign, Murphy brought Tammany Hall's political influence to the national level, specifically in 1924 when he and the Democratic Party were expected to nominate Alfred E. Smith for President. Murphy also influenced the elections of three New York City Mayors, three New York State Governors, and the impeachment of Governor William Sulzer.[1] Governor Sulzer was propelled into office by Tammany Hall; however, during his tenure, Sulzer distanced himself from Tammany politics, refused to follow its orders, and supported general primaries.[5] This angered both Tammany Hall and its boss, Murphy; with his help, the State Assembly voted to impeach Sulzer on counts of perjury and fraud.[5] Murphy's involvement in the impeachment of a former Tammany member demonstrates his tenacity and fierceness as a political figure. Murphy once said, “It is the fate of political leaders to be reviled. If one is too thin skinned to stand it he should never take the job. History shows the better and more successful the organization and the leader the more bitter the attacks”.[1]

Ed Flynn, a protégé of Murphy who became the boss in the Bronx, said Murphy always advised that politicians should have nothing to do with gambling or prostitution, and should steer clear of involvement with the police department or the school system.[6]

Death

Murphy died suddenly of what the New York Times termed "acute indigestion," which affected his heart, on April 25, 1924, at his home in New York City. A Roman Catholic, he was given a funeral service at St. Patrick's Cathedral and was buried at Calvary Cemetery in New York.[7]

In popular culture

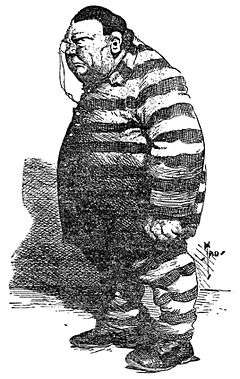

In the 1941 film Citizen Kane, screenwriters Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles based the character of political boss Jim Gettys on Charles F. Murphy.[8] William Randolph Hearst and Murphy were political allies in 1902, when Hearst was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, but the two fell out in 1905 when Hearst ran for mayor of New York City. Hearst was denied the election by a slim margin due to electoral fraud perpetrated by Murphy's organization, and his newspapers retaliated. A historic cartoon of Murphy in convict stripes appeared November 10, 1905, three days after the vote.[9] The caption read, "Look out, Murphy! It's a Short Lockstep from Delmonico's to Sing Sing … Every honest voter in New York wants to see you in this costume."[10]

In Citizen Kane, Boss Jim Gettys admonishes Kane for printing a cartoon showing him in prison stripes:

If I owned a newspaper and if I didn't like the way somebody else was doing things—some politician, say—I'd fight them with everything I had. Only I wouldn't show him in a convict suit with stripes—so his children could see the picture in the paper. Or his mother.

As he pursues Gettys down the stairs, Kane threatens to send him to Sing Sing.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Allbray, Nedda C. "Murphy, Charles Francis";http://www.anb.org/articles/06/06-00462.html; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

- 1 2 Allbray

- ↑ Teaford, Jon C. "Croker, Richard";http://www.anb.org/articles/05/05-00160.html;American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

- ↑ Lifflander, Matthew L. "The Tragedy That Changed New York" New York Archives (Summer 2011)

- 1 2 Lifflander, Matthew L. The Impeachment of Governor Sulzer: A Story of American Politics. Albany: State University of New York, 2012. Print.

- ↑ Terry Golway, Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics (2014) p 186

- ↑ "Chief is Stricken Suddenly; Arises in Pain, Sends for Doctor and Expires a Few Minutes Later"; The New York Times, April 26, 1924

- ↑ Kael, Pauline, "Raising Kane", book-length essay in The New Yorker (February 20 and 27, 1971); reprinted in The Citizen Kane Book. Kael, Pauline, Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles, The Citizen Kane Book. New York: Bantam Books, 1971, page 61

- ↑ Turner, Hy B., When Giants Ruled: The Story of Park Row, New York's Great Newspaper Street. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999 ISBN 0-8232-1944-5 pp. 150–152

- ↑ Current Literature, Vol. 41, No. 5, October 1906, page 477

- ↑ Mankiewicz, Herman J. and Orson Welles, shooting script for Citizen Kane reprinted in The Citizen Kane Book. Kael, Pauline, Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles, The Citizen Kane Book. New York: Bantam Books, 1971, pp. 219–225

Further reading

- "Charles F. Murphy" on The Political Graveyard

- Allbray, Nedda C. "Murphy, Charles Francis";http://www.anb.org/articles/06/06-00462.html; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

- Lifflander, Matthew L. The Impeachment of Governor Sulzer: A Story of American Politics. Albany: State University of New York, 2012. Print.

- Teaford, Jon C. "Croker, Richard";http://www.anb.org/articles/05/05-00160.html;American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

- Weiss, Nancy Joan. Charles Francis Murphy, 1858-1924: Respectability and Responsibility in Tammany Politics. Smith College, 1968

- Zink, Harold B. City Bosses in the United States: A Study of Twenty Municipal Bosses (1930) pp 147–63 online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles F. Murphy. |

- Charles Francis Murphy at Find a Grave

- Tammany Hall Links

- Entry in the 11th edition, otherwise known as 1911 edition, of the Encyclopaedia Britannica