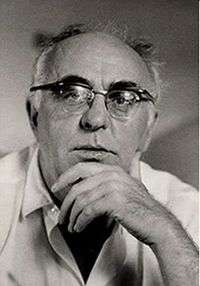

Charles Olson

| Charles Olson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

27 December 1910 Worcester, Massachusetts |

| Died |

10 January 1970 (aged 59) New York City, New York |

| Resting place | Gloucester, Massachusetts |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | B.A. and M.A. at Wesleyan University |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Literary movement | Postmodernism |

| Notable works | The Distances, The Maximus Poems |

| Spouse | Constance Wilcock, Betty Kaiser |

| Children | Katherine, Charles Peter |

| Relatives | Karl (Father), Mary Hines (Mother) |

|

| |

Charles Olson (27 December 1910 – 10 January 1970) was a second generation American poet who was a link between earlier figures such as Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams and the New American poets, which includes the New York School, the Black Mountain School, the Beat poets, and the San Francisco Renaissance. Consequently, many postmodern groups, such as the poets of the language school, include Olson as a primary and precedent figure. He described himself not so much as a poet or writer but as "an archeologist of morning."

Life

Olson was born to Karl Joseph and Mary Hines Olson and grew up in Worcester, Massachusetts, where his father worked as a mailman. Olson spent summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts, which was to become the focus of his writing. At high school he was a champion orator, winning a tour of Europe as a prize.[1] He studied literature and American studies, gaining a B.A and M.A at Wesleyan University.[2] For two years Olson taught English at Clark University then entered Harvard University in 1936 where he finished his coursework for a Ph.D. in American civilization but failed to complete his degree.[1] He then received a Guggenheim fellowship for his studies of Herman Melville.[2] His first poems were written in 1940.[3]

In 1941, Olson moved to New York and joined Constance "Connie" Wilcock in civil marriage, together having one child, Katherine. Olson became the publicity director for the American Civil Liberties Union. One year later, he and his wife moved to Washington, D.C., where he spent the rest of the war years working in the Foreign Language Division of the Office of War Information, eventually rising to Assistant Chief of the division.[2] (The chief of the division was the future senator from California, Alan Cranston.) In 1944, Olson went to work for the Foreign Languages Division of the Democratic National Committee. He also participated in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt campaign, organizing a large campaign rally at New York's Madison Square Garden called "Everyone for Roosevelt". After Roosevelt's death, upset over both the ascendancy of Harry Truman and the increasing censorship of his news releases, Olson left politics and dedicated himself to writing, moving to Key West, Florida, in 1945.[1] From 1946 to 1948 Olson visited poet Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington D.C., but was repelled by Pound's fascist tendencies.[3]

In 1951, Olson became a visiting professor at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, working and studying here beside artists such as John Cage and Robert Creeley.[2] He subsequently became rector of Black Mountain College and had a second child, Charles Peter Olson, with one of his students, Betty Kaiser. Before his divorce from his first wife finalized, Olson married Kaiser.

Olson's ideas came to deeply influence a generation of poets, including writers such as Denise Levertov, Paul Blackburn, Ed Dorn and Robert Duncan.[2] At 204 cm (6'8"), Olson was described as "a bear of a man", his stature possibly influencing the title of his Maximus work.[4] Olson wrote copious personal letters, and helped and encouraged many young writers. He was fascinated with Mayan writing. Shortly before his death, he examined the possibility that Chinese and Indo-European languages derived from a common source. When Black Mountain College closed in 1956, Olson settled in Gloucester, Massachusetts. He served as a visiting professor at the University at Buffalo (1963-1965) and at the University of Connecticut (1969).[2] The last years of his life were a mixture of extreme isolation and frenzied work.[3] Olson's life was marred by alcoholism, which contributed to his early death from liver cancer. He died in New York in 1970, two weeks past his fifty-ninth birthday, while in the process of completing The Maximus Poems.[5]

Work

Early writings

Olson's first book, Call Me Ishmael (1947), a study of Herman Melville's novel Moby Dick, was a continuation of his M.A. thesis from Wesleyan University.[6]

In Projective Verse (1950), Olson called for a poetic meter based on the poet's breathing and an open construction based on sound and the linking of perceptions rather than syntax and logic. He favored metre not based on syllable, stress, foot or line but using only the unit of the breath. In this respect Olson was foreshadowed by Ralph Waldo Emerson's poetic theory on breath.[7] The presentation of the poem on the page was for him central to the work becoming at once fully aural and fully visual[8] The poem "The Kingfishers" is an application of the manifesto. It was first published in 1949 and collected in his first book of poetry, In Cold Hell, in Thicket (1953).

Olson's second collection, The Distances, was published in 1960. Olson served as rector of the Black Mountain College from 1951 to 1956. During this period, the college supported work by John Cage, Robert Creeley, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Duncan, Fielding Dawson, Cy Twombly, Jonathan Williams, Ed Dorn, Stan Brakhage and many other members of the 1950s American avant garde. Olson is listed as an influence on artists including Carolee Schneemann and James Tenney.[9]

Olson's reputation rests in the main on his complex, sometimes difficult poems such as "The Kingfishers", "In Cold Hell, in Thicket", and The Maximus Poems, work that tends to explore social, historical, and political concerns. His shorter verse, poems such as "Only The Red Fox, Only The Crow", "Other Than", "An Ode on Nativity", "Love", and "The Ring Of" are more immediately accessible and manifest a sincere, original, emotionally powerful voice. "Letter 27 [withheld]" from The Maximus Poems weds Olson's lyric, historic, and aesthetic concerns. Olson coined the term postmodern in a letter of August 1951 to his friend and fellow poet, Robert Creeley.

The Maximus Poems

In 1950, inspired by the example of Pound's Cantos (though Olson denied any direct relation between the two epics), Olson began writing The Maximus Poems. An exploration of American history in the broadest sense, Maximus is also an epic of place, Massachusetts and specifically the city of Gloucester where Olson had settled. Dogtown, the wild, rock-strewn centre of Cape Ann, next to Gloucester, is an important place in The Maximus Poems. (Olson used to write outside on a tree stump in Dogtown.) The whole work is also mediated through the voice of Maximus, based partly on Maximus of Tyre, an itinerant Greek philosopher, and partly on Olson himself. The last of the three volumes imagines an ideal Gloucester in which communal values have replaced commercial ones. When Olson knew he was dying of cancer, he instructed his literary executor Charles Boer and others to organise and produce the final book in the sequence following Olson's death.[5]

Selected bibliography

- Call Me Ishmael. (1947; reprint, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997)

- Projective Verse (1950)

- The Distances. First Printing. (New York: Grove Press Inc., 1960)

- Human Universe and Other Essays, ed. Donald Allen (Berkeley, 1965)

- Archaeologist of Morning. London and New York: Cape Goliard, 1970

- Charles Olson and Robert Creeley: The Complete Correspondence, ed. George F. Butterick and Richard Blevins, 10 vols. (Black Sparrow Books, 1980–96)

- The Maximus Poems (Stuttgart, 1953 & 1956); (Corinth Books/Jargon 24, New York, 1960); (Berkeley, Calif. and London, 1983)

- The Collected Poems of Charles Olson (Berkeley, 1987)

- Collected Prose, eds. Donald Allen & Benjamin Friedlander (Berkeley, 1997)

- Selected Letters, ed. Ralph Maud (Berkeley, 2001)

References

- 1 2 3 "Charles Olson Biography (University of Connecticut Libraries)". Charlesolson.uconn.edu. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Olson profile at Academy of American Poets.

- 1 2 3 Stringer, Jenny (1996) The Oxford companion to twentieth-century literature in English OUP p511 ISBN 0-19-212271-1

- ↑ Olson (1992) Maximus to Gloucester: the letters and poems of Charles Olson to the editor of the Gloucester Daily Times, 1962-1969 Ten Pound Island Book Co p29 ISBN 978-0-938459-07-1

- 1 2 A Guide to The Maximus Poems of Charles Olson By George F. Butterick University of California Press, 'Introduction', (p xliv) 1981 ISBN 978-0-520-04270-4

- ↑ Olson, Charles, Donald M. Allen, and Benjamin Friedlander. "Editors' Notes," Collected Prose. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997: p. 379

- ↑ Schmidt, Michael The Lives of the Poets Wiedenfeld & Nicholson , London 1998 ISBN 9780753807453

- ↑ Schmidt, Michael, Lives of the Poets, Weidenfeld&Nicholson, London 1998

- ↑ "Carolee Schneeman speaks". Gregcookland.com. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

Further reading

- Butterick, George F. and Blevins, Richard Charles Olson and Robert Creeley: The Complete Correspondence 9 vols. (Berkeley, 1980–90)

- East, Elyssa Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town

- Merrill, Thomas F. The Poetry of Charles Olson: A Primer (Delaware, 1982).

- Maud, Ralph (editor) (2010) Muthologos: Lectures and Interviews. Revised Second Edition. Talonbooks, Vancouver, Canada. ISBN 978-0-88922-639-5.

- Butterick, George F.: "A Guide to the Maximus Poems," (University of California Press, 1981)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charles Olson |

- Olson Biography, University of Connecticut Libraries

- Olson profile at Academy of American Poets. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- Profile at Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- Olson at Modern American Poetry. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- Charles Olson at Find a Grave

- Works by or about Charles Olson in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Read Olson's interview with The Paris Review. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- The Charles Olson Research Collection (Archives) at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut Libraries. Retrieved 2010-12-12

- "Charles Olson in the Tradition of Walt Whitman", Essay on Olson as Visionary Poet. Retrieved 2012-29-02

- Polis Is This: Charles Olson and the Persistence of Place documentary on Olson by Henry Ferrini (1 hr). Retrieved 2010-12-12

- "Charles Olson", Pennsound, a page of Charles Olson recordings. Retrieved 2010-12-12