Chichimeca War

| The Chichimeca War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

The Chichimeca War (1550–90) was a military conflict waged between Spanish colonizers and their Indian allies against a confederation of Chichimeca Indians. It was the longest and most expensive conflict between Spaniards and the indigenous peoples of New Spain in the history of the colony.[1]

The Chichimeca wars began eight years after the Mixtón War of 1540–42. It can be considered as a continuation of the rebellion as the fighting did not come to a halt in the intervening years. Unlike in the Mixtón rebellion, the Caxcanes were now allied with the Spanish. The war was fought in the Bajío region known as La Gran Chichimeca, specifically in the Mexican states of Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, and San Luis Potosí.

Prelude

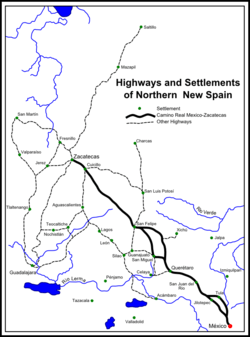

On September 8, 1546 Indians near the Cerro de la Bufa in what would become the city of Zacatecas showed the Spaniard Juan de Tolosa several pieces of silver-rich ore. News of the silver strike soon spread across Spanish Mexico. The dream of quick wealth triggered multitudes of people to migrate from southern Mexico to the city of Zacatecas in the heartland of La Gran Chichimeca.[2] Soon the mines of San Martín, Chalchihuites, Avino, Sombrerete, Fresnillo, Mazapil, and Nieves were established. The Chichimeca nations resented the intrusions by the Spanish and their Indian laborers and allies on their ancestral lands. Disobeying the Viceroy, Spanish soldiers soon began raiding native settlements of both friendly and unfriendly Indians to acquire slaves for the mines. To supply and communicate with the mines in and near Zacatecas, new roads were built from Querétaro and Jalisco across Chichimeca lands. The slow-moving caravans of carts and wagons full of goods along the roads were a tempting target for Chichimeca raiders.[3]

The Chichimecas

The Chichimecas were nomadic and semi-nomadic people who occupied the large desert basin stretching from present day Saltillo and Durango in the north to Querétaro and Guadalajara in the south. Within this area of about 60,000 square miles (160,000 km2) the Chichimecas existed primarily by hunting and gathering, especially mesquite beans, the edible parts of the agave plants, and the fruit (tunas) and leaves of cactus. In favored areas some of the Chichimeca grew corn and other crops. Their numbers are difficult to estimate, although based on the average density of nomadic populations they probably numbered 30,000 to 60,000.[4] The Chichimecas lived in rancherias of crude shelters or caves, frequently moving from one area to another to take advantage of seasonal foods and hunting. The characteristics most noted about them by the Spanish was that both women and men wore few if any clothes, grew their hair long, and painted and tattooed their bodies. They were often accused of cannibalism.[5]

The Chichimecas were not a single tribe or a united nation, but consisted or four different ethnic groups: Guachichiles, Pames, Guamares, and Zacatecos. None of these groups were politically united but rather consisted of many different independent tribes and bands.[6] Their territories overlapped and other Indian groups also joined one or another of the Chichimeca groups in raiding on occasion.

The Guachichiles’ territory centered on the area around what would become the city of San Luis Potosí. They seem to have been the most numerous of the four ethnic groups and the de facto leaders of the Chichimecas. Their name meant ‘head colored red” and they colored both their skin and clothing that color. Living in close proximity to the silver road between Querétaro and Zacatecas, they were the most feared of the Indian raiders.[7]

The Pames lived north of Querétaro and south and east of the Guachichiles. They were the least warlike and dangerous of the Chichimecas – primarily raiders of livestock. They had absorbed some of the religious and cultural practices of the more urbanized Indian nations to their south.[8]

The Guamares lived mostly in present-day Guanajuato. They possibly had more political unity than the other Chichimecas and were considered by one writer as the most "treacherous and destructive of all the Chichimecas and the most astute.”[9]

The Zacatecos lived in the present day states of Zacatecas and Durango. They had participated in the earlier Mixtón War and thus were experienced fighters against the Spanish. Some of the Zacatecos grew maize; others were nomadic.

The nomadic lifestyle and dispersed settlements of the Chichimecas contributed to the difficulty the Spanish had in defeating them. The bow was their principal weapon and one experienced observer said the Zacatecos were “the best archers in the world.” Their bows were short, usually less than four feet long, their arrows were long and thin and made of reed and tipped with obsidian. Despite the apparent fragility of the arrows they had excellent penetrating qualities, even against Spanish armor which was de rigueur for soldiers fighting the Chichimeca. Many-layered buckskin armor was preferred to chain mail as arrows could penetrate the links of the mail.[10]

Chichimeca battle tactics were mostly ambushes of travelers and caravans, livestock raids, and attacks on isolated settlements of sedentary Indians and Spanish colonists. Although some of their raids were conducted by up to 200 men, groups of 40 to 50 warriors were more common. During the war, the Chichimecas learned to ride horses and use them in war. This was perhaps the first time that the Spanish in North America faced mounted Indian warriors.[11]

Course of the war

The conflict proved much more difficult and enduring than the Spanish anticipated. The Chichimecas seemed primitive and unorganized. But they proved to be a many-headed hydra. Although the Spanish often attacked and defeated bands of Chichimecas, Spanish military successes had little impact on other independent groups who continued the war. The first outbreak of hostilities was in late 1550 when Zacatecos attacked a supply caravan of Purépecha en route to Zacatecas. A few days later they were attacking ranches less than 10 miles (16 km) south of Zacatecas. In 1551 the Guachichile and Guamares joined in, in one instance killing 14 people near the outpost of San Miguel de Allende and forcing its temporary abandonment. Other raids near Tlaltenango were reported to have killed 120 people, mostly Indians friendly to the Spanish, within a few months. The most damaging raids of the early years of the war took place in 1553 and 1554 when two large wagon trains on the road to Zacatecas were attacked, people killed, and the very substantial sums of 32,000 and 40,000 pesos in goods stolen or destroyed. (By comparison, the annual salary of a Spanish soldier was only 300 pesos.) By the end of 1561 it was estimated that more than 200 Spaniards and 2,000 Indian allies and traders had been killed by the Chichimecas. Prices for imported food and other commodities in Zacetacas had doubled or tripled due to the dangers of transporting the goods to the city. In the 1570s the rebellion spread as Pames began raiding near Querétaro.[12]

The Spanish government first attempted measures of both carrot and stick to attempt to damp down the war, but, those failing, in 1567 it adopted the policy of a “war of fire and blood” (fuego y sangre) – promising death, enslavement, or mutilation to the Chichimeca. The top priority of the Spaniards throughout the war was to keep the roads open to Zacatecas and the silver mines – especially the Camino Real from San Miguel de Allende. To do so they created a dozen new presidios (forts), staffed by Spanish and Indian soldiers, and encouraged settlers in new areas, including what would be the nucleus of the future cities of Celaya, León, Aguascalientes, and San Luis Potosí.

The increase in number of Spanish soldiers in the Gran Chichimeca was not entirely favorable to the war effort as the soldiers often supplemented their income by slaving, thus reinforcing the animosity of the Chichimeca. Moreover, the Spanish were short of soldiers, often staffing their presidios with only three Spaniards. They relied heavily, as they had in the past, on Indian soldiers and auxiliaries, especially the Caxcans (whom they had defeated in the Mixtón War), the Purépecha, and the Otomi. The Indian allies were rewarded with lands and stipends and were allowed to ride horses and carry swords, formerly banned for use by Indians.[13]

Peace by Purchase

As the war continued unabated, it became clear that the Spanish policy of a war of fire and blood had failed. The royal treasury was being emptied by the demands of the war. Churchmen and others who had initially supported the war of fire and blood now questioned the policy. Mistreatment and enslavement of the Chichimeca by Spaniards increasingly came to be seen as the cause of the war. In 1574, the Dominicans, contrary to the Augustinians and Franciscans, declared that the Chichimeca War was unjust and caused by Spanish aggression.[14] Thus, to end the conflict, the Spanish began to work toward an effective counter insurgency policy which rewarded the Chichimeca for peaceful behavior while taking steps to assimilate them.

In 1584, the Bishop of Guadalajara made a proposal for a “Christian remedy” to the war: the establishment of new towns with priests, soldiers, and friendly Indians to gradually domesticate and Christianize the Chichimecas. The Viceroy, Alvaro Manrique de Zuniga, followed this idea in 1586 with a policy of removing many Spanish soldiers from the frontier as they were considered more a provocation than a remedy. The Viceroy opened negotiations with Chichimeca leaders and promised them food, clothing, land, priests, and tools to encourage them through “gentle persuasion” to settle down. He forbade military operations to seek out and capture and kill hostile Indians. One of the key people behind these negotiations was Miguel Caldera, a captain who was of both Spanish and Guachichile desecent. Beginning in 1590 and continuing for several decades the Spanish implemented the “Peace by Purchase” program by sending large quantities of goods northward to be distributed to the Chichimecas. In 1590 the Viceroy declared the program a success and the roads to Zacatecas safe for the first time in 40 years.[15]

The next step, in 1591, was for a new Viceroy, Luis de Velasco, with help from others such as Caldera, to persuade 400 families of Tlaxcalan Indians, old allies of the Spanish, to establish eight settlements in Chichimeca areas. They served as Christian examples to the Chichimecas and taught animal husbandry and farming to them. In return for moving to the frontier, the Tlaxcalans extracted concessions from the Spanish, including land grants, freedom from taxes, the right to carry arms, and provisions for two years. The Spanish also took steps to curb slavery on Mexico's northern frontier by ordering the arrest of members of the Carabajal family and Gaspar Castaño de Sosa. An essential part of their strategy was conversion of the Chichimeca to Catholicism. The Franciscans sent priests to the frontier to aid in the pacification effort.[16]

The Peace by Purchase program worked. Hostilities died down and the majority of the Chichimecas gradually became sedentary, Catholic or nominally Catholic, and peaceful.

Importance

The Spanish policy which evolved to pacify the Chichimecas had four components: negotiation of peace agreements, converting Indians to Christianity with missionaries, resettling Native Americans allies to the frontier to serve as examples and role models, and providing food, other commodities, and tools to potentially hostile Indians to encourage them to become sedentary. This established the pattern of Spanish policy for assimilating Native Americans on their northern frontier. The principal components of the policy of peace by purchase would continue for nearly three centuries and would not be uniformly successful, as later threats from hostile Indians such as Apaches and Comanches would demonstrate.

Chichimecas today

Over time most of the Chichimeca people lost their ethnic identities and were absorbed into the mestizo population of Mexico. The Zacatecos and Guamares totally disappeared as distinct peoples.

The Huicholes are believed to be the descendants of the Guachichiles.[17][18] About 20,000 of them live in an isolated area on the borders of Jalisco and Nayarit. They are noted for being conservative, successfully preserving their language, religion, and culture.[18][19]

There are about 10,000 speakers of the Pame languages in Mexico, primarily in the municipality of Santa Maria Acapulco in an isolated region in southeastern San Luis Potosí province. They are conservative and nominal Catholics, but mostly still practicing their traditional religion and customs.[20][21] Another group of about 1,500 Chichimeca Jonaz live in the state of Guanajuato.[22]

References

- ↑ LatinoLA | Comunidad :: The Indigenous People of Zacatecas

- ↑ Bakewell, P. J. Silver Mining and Society in Colonial Mexico: Zacatecas, 1546-1700. Cambridge: Cambridge U Press, 1971, pp. 4-14

- ↑ Schmal, John P. “The Indigenous People of Zacatecas.” , accessed Jan 10, 2011

- ↑ Marlowe, Frank W. “Hunter-Gatherers and Human Evolution.” Evolutionary Anthropology. Vol 14, 2005, p. 57. Average and median population densities for the New World.

- ↑ Powell, Phillip Wayne Soldiers, Indians & Silver. Berkeley: U of CA Press, 1952, pp. 39-41

- ↑ Powell, pp. 33-35

- ↑ Powell, pp. 35-37

- ↑ Powell, p. 37

- ↑ Powell, p. 38

- ↑ Powell, p. 48

- ↑ Powell, pp. 43-54

- ↑ Powell, pp. 29-30, 60-62, 124

- ↑ Powell, pp. 158-171

- ↑ Gradie, Charlotte M. The Tepehuan Revolt of 1616. Salt Lake City: U of UT Press, 2000, p. 47

- ↑ Powell, pp. 182-190

- ↑ Powell, pp. 191-199

- ↑ Schaefer, Stacy B. and Furst, Peter T. People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion, and Survival, Albuquerque: U of NM Press, 1997, p. 40-41

- 1 2 Ethnologue report for language code: hch

- ↑ Schaefer and Furst, p. 40

- ↑ Lugares de México - Santa María Acapulco

- ↑ http://davidmarkham.org/updates/1992_06.htm[]

- ↑ Schmal, John P. "A Look into Guanajuato's Past."

- Sources

| Library resources about Chichimeca War |

- Powell, Philip Wayne. Soldiers, Indians, & Silver: The Northward Advance of New Spain, 1550-1600. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1952 (republished 1969)

- Schmal, John P. The History of Zacatecas. Houston Institute for Culture. 2004.

- Schmal, John P. Sixteenth Century Indigenous Jalisco. 2004.