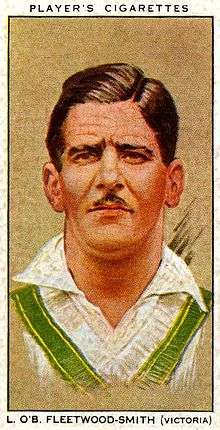

Chuck Fleetwood-Smith

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Leslie O'Brien Fleetwood-Smith | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

30 March 1908 Stawell, Victoria, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died |

16 March 1971 (aged 62) Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | Chuck | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting style | Right-hand | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling style | Left-arm wrist spin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Specialist bowler | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 153) | 14 December 1935 v South Africa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 20 August 1938 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1931–1940 | Victoria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Cricinfo, 19 November 2007 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Leslie O'Brien "Chuck" Fleetwood-Smith (30 March 1908 – 16 March 1971) was a cricketer who played for Victoria and Australia. Known universally as "Chuck", he was the "wayward genius" of Australian cricket during the 1930s. A slow bowler who could spin the ball harder and further than his contemporaries, Fleetwood-Smith was regarded as a rare talent, but his cricket suffered from a lack of self-discipline that also characterised his personal life.[1] In addition, his career coincided with those of Bill O'Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett, two spinners named in the ten inaugural members of the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame; as a result he played only ten Test matches but left a lasting impression with one delivery in particular. His dismissal of Wally Hammond in the fourth Test of the 1936–37 Ashes series has been compared to Shane Warne's ball of the century. He has the unwanted record of conceding the most runs by a bowler in a Test match innings.

Holding little regard for the other disciplines of the game, batting and fielding, he attracted a lot of attention with his rare style of bowling: left-arm wrist spin. Sometimes called the "chinaman", or left-arm unorthodox, few bowlers of this type have appeared in senior cricket. Certainly, Fleetwood-Smith was the first chinaman bowler influence Australian cricket and play for the Test team.[2]

Fleetwood-Smith was ambidextrous and could bowl with either arm during his youth. His choice of an unconventional bowling style reflected his reputation as an eccentric.[3] After his playing days finished, Fleetwood-Smith succumbed to alcoholism and spent many years homeless on the streets of Melbourne, sometimes sleeping rough a few hundred metres from the stadium where he played many of his best matches, the Melbourne Cricket Ground. His arrest in 1969 brought attention to his plight and a number of influential people rallied to his cause.

Early years

The third child of Fleetwood Smith and his wife Frances (née Swan), Fleetwood-Smith was born at Stawell in the Northern Grampians area of western Victoria.[4] The family was well known in the district for their long involvement with the local newspaper, and for Fleetwood Smith's association with the organising committee of the Stawell Gift. During his infancy, Fleetwood-Smith was given the nickname "Chuck", a contraction of the polo term "chukka".[3] After attending primary school in Stawell, he enrolled at Xavier College when the family moved to Melbourne in 1917.[4] In the early 1920s, he was a member of Xavier's powerful First XI, which included the future Test player Leo O'Brien and Karl Schneider, who played first-class cricket while still at the school, but died of leukaemia at the age of 23.[5] The team won the Victorian Public Schools premiership in 1924, but Fleetwood-Smith left the school soon after. It is believed that he was expelled, although the school records are incomplete and do not mention this.[6]

Returning to Stawell, where his family had relocated a year earlier, Fleetwood-Smith completed his education locally and turned out for the Stawell cricket team in the Wimmera league. In three seasons from 1927 to 1928, he captured 317 wickets for Stawell and took seven wickets in a representative match, playing for the Country Colts against the City Colts. He came to the attention of cricket clubs in Melbourne while representing the league in a Country Week tournament.[7] Around this time, his father decided to combine his first and last names, and the family styled themselves as Fleetwood-Smith.[8]

Cricket career

Fleetwood-Smith moved to Melbourne to play with St Kilda in the district cricket competition for the 1930–31 season. It was a challenging choice for a young bowler as the team possessed an outstanding spin attack—Test bowlers Bert Ironmonger and Don Blackie were members of the club.[3] He became a regular in the club's First XI during his second season and in one match claimed 16 wickets for 82 runs (16/82) against Carlton, prompting his selection for the Victorian second team.[9] The remainder of the summer was meteoric for Fleetwood-Smith. He made his first-class debut against Tasmania and captured ten wickets; in his first international against the touring South Africans he returned 6/80 in the first innings; and on his Sheffield Shield debut, he took 11 wickets for the match against South Australia.[10] He led the first-class bowling averages for Victoria and capped the season by playing in St Kilda's premiership team.[11] In the winter of 1932, Fleetwood-Smith joined a private tour of the United States and Canada, organised by the former Test spin bowler Arthur Mailey. Playing 51 matches, he totalled 249 wickets at an average of less than eight runs each as his unique style bewildered the local batsmen.[4]

On the fringe of the Test team

This rapid rise made Fleetwood-Smith a prospect for the Test team in 1932–33 when England toured and played the famous Bodyline series.[3] However, in Ironmonger, Bill O'Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett, the Australian team possessed a strong spin bowling attack and Fleetwood-Smith needed to supplant one of the trio to gain selection. Although he took 50 first-class wickets for the season (at 21.90 average, including 9/36 in an innings against Tasmania),[12] his bowling received rough treatment from Don Bradman in a match against New South Wales.[13] In the tour match against England that followed, Wally Hammond was given specific instructions to attack the inexperienced Fleetwood-Smith and remove him from consideration for the Test matches, which he accomplished during an innings of 203.[14] The England manager, Plum Warner, later wrote that too much attention was given to this performance and he was sanguine about Fleetwood-Smith's potential as a Test bowler.[15] Despite Grimmett's absence from the Australian team—he was dropped after the third Test—the Australian selectors opted not to gamble by choosing Fleetwood-Smith. Instead, they called on the all-rounders Ernie Bromley and "Perka" Lee.

The following season, Fleetwood-Smith transferred from St Kilda to the Melbourne club as they had found him employment.[16] He collected 41 wickets for Victoria in seven matches, with a best match return of 12/158 against South Australia.[3] This earned him a place in the Australian team for the 1934 tour of England. With Grimmett returned to favour, Fleetwood-Smith was unable to gain selection in the Test matches despite taking 106 first-class wickets (at a cost of 19.20 runs each) on the tour.[12] Initially sceptical of his ability, Wisden thought that his bowling was "erratic" during the early part of the tour, but that he improved dramatically during the second half of the season.[17] Against Sussex, Northants and HDG Leveson-Gower's XI, he took ten wickets for the match. In the latter game, he bowled an inspired spell to Maurice Leyland, the most prolific English batsman of the Test series. Leyland had great success in dealing with O'Reilly and Grimmett, but could not fathom Fleetwood-Smith's various deliveries.[18]

During the 1934–35 season, Fleetwood-Smith set a new Sheffield Shield record of 60 wickets in six matches, which remained until Colin Miller claimed 67 wickets in 11 matches in 1997–98.[19] He dominated Victoria's bowling—the next best was Ernie McCormick with 22 wickets—as the team won the Sheffield Shield.[20] In the match that effectively decided the title, Fleetwood-Smith took 15 wickets against a New South Wales team that included nine Test players.[21] He guided the Melbourne club to the premiership in the district competition with seven wickets in the final against Collingwood. Chosen to tour South Africa during the following summer, he made his belated Test debut in the opening match of the series at Durban. Taking the wicket of Ken Viljoen in his first over, Fleetwood-Smith finished the match with five wickets. He played the next two Tests (for four wickets), but injured his hand while fielding his own bowling in a tour match against Border. This forced him out of the remaining matches on the tour and caused him problems in the forthcoming months.

Ashes series 1936–37

Following his return to Australia, Fleetwood-Smith had surgery to a tendon in his finger and missed the early stages of the 1936–37 season.[3] In his absence, Australia lost the opening two Tests of The Ashes series against England amid claims that the players were not responding well to their new captain, Don Bradman.[22] Grimmett, now considered by the selectors to be too old for Test cricket, was not selected during the series. Therefore, Fleetwood-Smith recorded career-best figures at an opportune time. Playing against Queensland he captured 7/17 and 8/79, then secured his selection for the Test team with a five-wicket haul against New South Wales.[23] In the third Test at Melbourne, he contributed to Australia's victory with a valuable innings as a nightwatchman and 5/124 in England's second innings as they were bowled out for 323, chasing a victory target of 689 runs.[24]

Immediately after the match, Fleetwood-Smith, O'Reilly, Leo O'Brien and Stan McCabe were summoned to appear before four of Australia's leading cricket administrators, who read a prepared statement accusing the team of excessive drinking, inattention to fitness and disloyalty to the captain. The meeting ended in confusion when the four players were told that they were not being held responsible for the matters raised.[25] This incident has been the subject of conjecture for many years. It is often interpreted as an illustration of a sectarian divide in Australian cricket during the period. Fleetwood-Smith attended Xavier (a Roman Catholic school) with O'Brien, while McCabe and O'Reilly were raised as Catholics in rural New South Wales; at least two of the administrators present were members of Masonic lodges.[26] Several of the senior players wanted McCabe as captain in place of Bradman, whose relationship with O'Reilly was strained.[27] However, Fleetwood-Smith's presence is puzzling as he missed the first two Tests, to which the administrators specifically referred.[28] Greg Growden, his biographer, records that Fleetwood-Smith had an unlikely friendship with Bradman (in that the two men were of opposite personalities), which later cooled after an unknown disagreement not associated with this incident.[29][30]

Fleetwood-Smith took four wickets in England's first innings of the fourth Test at Adelaide. Set a target of 392 runs to win, England reached 3/148 in their second innings by stumps on the fifth day, with their leading batsman Wally Hammond 39 not out and the match evenly poised.[31] At the beginning of the last day's play, Bradman gave Fleetwood-Smith the ball and told him, simply, that the fate of the match was in his hands.[32] Before Hammond could add to his overnight score, Fleetwood-Smith delivered a perfectly flighted off-break that drew Hammond forward as it curved away in the air. It then pitched and spun in the opposite direction to its trajectory, went between Hammond's bat and pad, and bowled him. The rest of the English batting fell for the addition of only 94 runs as Fleetwood-Smith advanced his figures to 6/110, giving him ten wickets for the match. Australia had levelled the series at two-all. Neville Cardus wrote:

Australia would have lost at Adelaide but for Fleetwood-Smith. Chuck took four years to gain revenge. He was suddenly visited by genius. Moreover he sucked the sweet blood of vengeance against Hammond. A lovely ball lured Hammond forward, broke at the critical length, evaded the bat and bowled England's pivot and main hope ... This achievement set a crown on the most skilful artistic spin bowler of the day.[33]

O'Reilly described it as the best delivery he ever witnessed in a Test match.[34] Bradman wrote, "If ever the result of a Test match can be said to have been decided by a single ball, this was the occasion."[32] After the match, thousands of spectators gathered in front of the pavilion and chanted his name until he came out to greet them. Later, he was given a civic reception in his home town of Stawell to celebrate his achievement.[9]

Australia amassed 604 in the first innings of the deciding Test at Melbourne, then bowled England out twice to win the match by an innings and 200 runs, thus retaining the Ashes. Fleetwood-Smith claimed four wickets to leave him second to Bill O'Reilly.

Second tour of England and after

Fleetwood-Smith's second tour of England in 1938 was less successful than his first. His 88 first-class wickets included match analyses of 8/70 against Somerset and 8/74 against Notts. Wisden noted that he succeeded mainly against batsmen unfamiliar with his method and offered this ambivalent assessment: "He could not be written down as a failure but he certainly fell below expectations ..."[35] However, he played in every Test of the series for the only time in his career. His seven wickets in the fourth Test at Leeds gave crucial support to O'Reilly, whose 10/122 was the key factor in the victory that enabled Australia to retain The Ashes.

In the final match of the series at The Oval, England went in first on a pitch ideal for batting and made a record total of 7/903, with their opening batsman Len Hutton making 364 to break Bradman's Ashes record score. England won by the overwhelming margin of an innings and 579 runs. Fleetwood-Smith conceded a world record of 298 runs in his 87 overs, for the wicket of Wally Hammond.[36] By contrast, O'Reilly's 85 overs cost him 178 runs. This had a dramatic impact on his average. Before the match it was 31.02; after, it was 37.38.[3]

For Victoria, Fleetwood-Smith captured 246 wickets at 24.56 runs per wicket in 40 Sheffield Shield matches, and in 51 matches for Victoria from 1931 to 1932 to 1939–40, Fleetwood-Smith captured 295 wickets at 24.39. He captured five wickets in an innings 31 times, 10 times going on to capture ten wickets in a match, both records for Victoria.[3]

Context

Style

Of above average height, Fleetwood-Smith was broad-shouldered and solidly built. He possessed strong wrists and fingers, developed by squeezing a squash ball,[4] which enabled him to spin the ball hard—teammates and opponents spoke of the "buzzing" or "fizzing" noise that the ball made on its way toward the batsman after leaving his hand.[9] Fleetwood-Smith's approach to bowling was uncomplicated. Following a very brief five-pace run up to the wicket, he brought his arm over quickly to deliver at a pace considered fast for a spin bowler.[1] His three variations were the off-break (spinning into the right-hand batsman), the wrong 'un (spinning away) and the top spinner, which Hammond believed to be his best ball. He did not bother with varying his pace or flight: the only concession he made to tactical considerations was a signal to the wicket-keeper, to let him know which of the three variations he was about to deliver.[37] Therefore, he rarely engaged in an extended strategic battle with a batsman in the manner of Grimmett or O'Reilly. The danger to the batsman lay in his unpredictability; he bowled all of his variations with no discernible change to his bowling action and needed no help from the pitch to extract turn. Bradman summarised:

At his top he would deceive anybody as to which way the ball would turn, and his great spin and nip off the pitch were most disconcerting. This necessarily brought inaccuracy in its train, and many a time he became the despair of his captain because of his loss of control.[38]

Comparisons

During the 1930s, Australia's bowling attack was dominated by spinners, specifically Grimmett and O'Reilly. Their stature in Australian cricket history saw them inducted into the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame in 1996 as one of the ten inaugural members, and they were the only two spinners in the first ten. Fleetwood-Smith's 42 Test wickets placed him fifth on the list of Australian wicket-takers for the period despite playing in only ten of Australia's 39 Test matches. The only fast bowlers of note on this list are Tim Wall (48 wickets in 17 matches) and Ernie McCormick (36 wickets in 12 matches).[39] Apart from the occasions when rain intervened to create a sticky wicket, the period was characterised by pitches prepared to favour batting. This so-called "doping" of pitches created controversy at the time and even Bradman argued for greater consideration for the bowlers.[40] Despite his flaws in other areas of the game, Fleetwood-Smith's ability to take wickets quickly was invaluable. In first-class cricket, his strike rate of 44.16 balls per wicket is superior to those of Grimmett and O'Reilly. However, his economy rate (i.e. the number of runs conceded per over) is almost 50% higher than that of O'Reilly, reflecting his relative inaccuracy.

| Matches | Wickets | Average | 5w/inns | 10w/m | Str/Rate | Eco/Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grimmett[41] | 248 | 1424 | 22.28 | 127 | 33 | 51.57 | 2.59 |

| O'Reilly[42] | 135 | 774 | 16.60 | 63 | 17 | 48.16 | 2.06 |

| Fleetwood-Smith[12] | 112 | 597 | 22.64 | 57 | 18 | 44.16 | 3.07 |

Eccentricities and personality

Chuck you must remember was just silly, and totally around the bend ... As for his cricketing ability ... well, if I only had half of it, I never would have been worried about bowling against a team which had eleven Bradmans.— Bill O'Reilly[43]

Fleetwood-Smith was famed for his eccentric nature on the field. He would sing, whistle, practice his golf swing, imitate birds such as magpies and kookaburras, pretend to catch imaginary butterflies, and shout encouragement for his favourite football team, Port Melbourne.[9] While playing in England, he liked to chant Lord Hawke's name and chat to the spectators with his back to the play.[44] His inattention to batting and fielding exasperated his teammates; he was quoted as saying, "if you can't be the best batsman in the world, you might as well be the worst."[45]

In addition to the affectation of his hyphenated surname, Fleetwood-Smith usually listed his year of birth as 1910 (thus reducing his age by two years) and propagated a story among journalists that he became a left-arm bowler when he broke his right arm during his youth.

Personal life

On 28 February 1935, Fleetwood-Smith married Mary "Mollie" Elliott at St Mary's Catholic Church in East St Kilda. The wedding was a society event widely covered by the newspapers. Her family was well known in Melbourne for owning a prosperous soft-drink business; her father was an alderman of the city.[4] Fleetwood-Smith had a reputation as a ladies' man who traded on his resemblance to the actor Clark Gable, and his infidelities after his marriage were not discreet. He joined the Elliotts' business as a sales representative, which brought him into daily contact with the pub trade and increased his alcohol consumption.

After the outbreak of World War II, Fleetwood-Smith enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force and was posted to the Army's Physical and Recreational Training School at Frankston where he served alongside Don Bradman as a Warrant Officer. He was involved in a collision with a nightcart when driving a borrowed army vehicle and the matter ended in court where he was ordered to pay costs.[46] After less than a year's service, he was given a medical discharge in February 1941.[4]

Fleetwood-Smith played the first post-war cricket season of 1945–46 for the Melbourne club and then retired with a tally of 252 wickets at 17.52 average in 74 district cricket matches, including four premiership teams.[3] By this time, his marriage had broken down and his wife petitioned for divorce in June 1946, which was granted the following year. This alienated him from his family in Stawell as his ex-wife remained close to the Fleetwood-Smiths. He had lost his job with the Elliotts' company during the war.[47] Fleetwood-Smith married Beatrix Collins (the sister of a teammate at Melbourne) at a registry office on 9 July 1948.[4] He worked intermittently at menial jobs and his drinking increased; his second marriage also failed.[9]

His arrest for vagrancy and theft in March 1969 was widely covered by the media. Appalled by his circumstance, a number of influential friends from his cricketing days, such as the former Australian Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies, aided him by organising him legal assistance. The hearing was later adjourned, and he reconciled with his wife Bea after committing to remain sober. They lived together again for the last years of his life. However, the years of homelessness left him in poor health, and he died from cancer at St Vincent's Hospital in Fitzroy a fortnight before his 63rd birthday.

Notes

- 1 2 Cashman et al. (1996), p 197.

- ↑ Rediff.com: Long march for the Chinamen. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Williams (2000), pp 52–54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Australian Dictionary of Biography: Fleetwood-Smith, Leslie O'Brien (1908–1971). Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ↑ The Age: Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 28.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 34.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coleman (1993), pp 443–439.

- ↑ Coleman (1993), p 393.

- ↑ Growden (1991), pp 42–47.

- 1 2 3 Cricket Archive: First-class bowling by Chuck Fleetwood-Smith. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 65.

- ↑ Cricinfo: Bodyline timeline, November 1932. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 66.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 67.

- ↑ Wisden, 1935 edition: The Australians in England 1934. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 53.

- ↑ Most Wickets in a Season in Australia Domestic First-Class Competition. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ↑ Cricinfo: Victorian Sheffield Shield Averages 1934–35. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ↑ Cricinfo: NSW v Victoria at Sydney 1934–35, scorecard. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ↑ Haigh and Frith (2007), p 92.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p. 111.

- ↑ Wisden, 1938 edition: 3rd Test Australia v England, match report. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ↑ Haigh and Frith (2007), p 93.

- ↑ Haigh and Frith (2007), p 94.

- ↑ Haigh and Frith (2007), p. 95.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p. 118.

- ↑ Growden (1991), pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p. 166.

- ↑ Wisden, 1938 edition: 4th Test Australia v England, match report. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- 1 2 Bradman (1950), p 103.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 122.

- ↑ Pollard (1988), p 453.

- ↑ Wisden, 1939 edition: The Australians in England 1938. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ↑ Cricket Archive: Most runs conceded in an innings in Test cricket. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 99.

- ↑ Bradman (1950), p 292.

- ↑ Cricinfo: Most wickets, 1930s Test matches. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ↑ Wisden, 1939 edition: Cricket at the crossroads. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ↑ Cricket Archive: First-class bowling by CV Grimmett. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ↑ Cricket Archive: First-class bowling by WJ O'Reilly. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 97.

- ↑ Growden (1991), pp 141–143.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 83.

- ↑ Growden (1991), pp 163–165.

- ↑ Growden (1991), p 165.

References

|