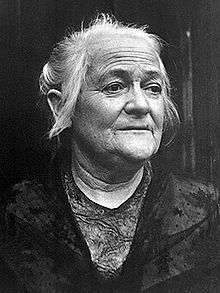

Clara Zetkin

| Clara Zetkin | |

|---|---|

Clara Zetkin (ca. 1920) | |

| Born |

Clara Josephine Eißner 5 July 1857 Wiederau, Saxony |

| Died |

20 June 1933 (aged 75) Arkhangelskoye, near Moscow |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation |

Politician Peace activist Women's rights activist |

| Political party |

SPD (till 1917) USPD (1917–1922) (Spartacus wing) KPD (1920–1933) |

| Partner(s) | Ossip Zetkin (1850–1889) |

| Children |

Maxim Zetkin (1883–1965) Konstantin "Kostja" Zetkin (1885–1980) |

| Parent(s) |

Gottfried Eißner Josephine Vitale/Eißner |

Clara Zetkin (née Eissner; 5 July 1857 – 20 June 1933) was a German Marxist theorist, activist, and advocate for women's rights.[1]

Until 1917, she was active in the Social Democratic Party of Germany,[2] then she joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) and its far-left wing, the Spartacist League; this later became the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which she represented in the Reichstag during the Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1933.[3]

Life and work

The eldest of three children, Clara Zetkin was born Clara Josephine Eissner in Wiederau, a peasant village in Saxony, now part of the municipality Königshain-Wiederau.[4] Her father, Gottfried Eissner, was a schoolmaster and church organist who was a devout Protestant, while her mother, Josephine Vitale, had French roots, came from a middle-class family from Leipzig, and was highly educated.[4][5][6] Having studied to become a teacher, Zetkin developed connections with the women's movement and the labour movement in Germany from 1874. In 1878 she joined the Socialist Workers' Party (Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei, SAP). This party had been founded in 1875 by merging two previous parties: the ADAV formed by Ferdinand Lassalle and the SDAP of August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht. In 1890 its name was changed to its modern version Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

_1987%2C_MiNr_3085.jpg)

Because of the ban placed on socialist activity in Germany by Bismarck in 1878, Zetkin left for Zurich in 1882 then went into exile in Paris. During her time in Paris she played an important role in the foundation of the Socialist International socialist group.[1] She also adopted the name of her lover, the Russian-Jewish leftist Ossip Zetkin, with whom she had two sons, Kostantin (Kostja) and Maxim. Ossip Zetkin died in 1889. Later, Zetkin was married to the artist Georg Friedrich Zundel, eighteen years her junior, from 1899 to 1928.[7]

In the SPD, Zetkin, along with Rosa Luxemburg, her close friend and confidante, was one of the main figures of the far-left wing of the party. In the debate on Revisionism at the turn of the 20th century they jointly attacked the reformist theses of Eduard Bernstein.[8]

Zetkin was very interested in women's politics, including the fight for equal opportunities and women's suffrage. She developed the social-democratic women's movement in Germany; from 1891 to 1917 she edited the SPD women's newspaper Die Gleichheit[lower-alpha 1] (Equality). In 1907 she became the leader of the newly founded "Women's Office" at the SPD. She also contributed to International Women's Day.[10][11] In August 1910, an International Women's Conference was organized to precede the general meeting of the Socialist Second International in Copenhagen, Denmark.[12] Inspired in part by American socialists' actions, Luise Zietz proposed the establishment of an annual International Woman's Day (singular) and was seconded by Zetkin, although no date was specified at that conference.[10][11] Delegates (100 women from 17 countries) agreed with the idea as a strategy to promote equal rights including suffrage for women.[13] The following year on March 19, 1911 IWD was marked for the first time, by over a million people in Austria, Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland.[14]

However, Zetkin was deeply opposed to the concept of "bourgeois feminism," which she claimed was a tool to divide the unity of the working classes.[15]

During the First World War Zetkin, along with Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Luise Kähler and other influential SPD politicians, rejected the party's policy of Burgfrieden (a truce with the government, promising to refrain from any strikes during the war).[16] Among other anti-war activities, Zetkin organised an international socialist women's anti-war conference in Berlin in 1915.[17] Because of her anti-war opinions, she was arrested several times during the war, and in 1916 taken into "protective custody" (from which she was later released on account of illness).[1]

In 1916 Zetkin was one of the co-founders of the Spartacist League[1] and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) which had split off in 1917 from its mother party, the SPD, in protest at its pro-war stance. In January 1919, after the German Revolution in November of the previous year, the KPD (Communist Party of Germany) was founded; Zetkin also joined this and represented the party from 1920 to 1933 in the Reichstag.[18] She interviewed Lenin on "The Women's Question" in 1920.[19]

Until 1924 Zetkin was a member of the KPD's central office; from 1927 to 1929 she was a member of the party's central committee. She was also a member of the executive committee of the Communist International (Comintern) from 1921 to 1933. In 1925 she was elected president of the German left-wing solidarity organisation Rote Hilfe. In August 1932, as the chairwoman of the Reichstag by seniority, she was entitled to give the opening address, and used it to call for workers to unite in the struggle against fascism.

She was a recipient of the Order of Lenin (1932) and the Order of the Red Banner (1927).[7]

When Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party took over power, the Communist Party of Germany was banned, following the Reichstag fire in 1933. Zetkin went into exile for the last time, this time to the Soviet Union. She died there, at Arkhangelskoye, near Moscow, in 1933, aged nearly 76.[1] Her ashes were placed in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis,[1] by the Moscow Kremlin Wall, near the Red Square.

After 1949, Zetkin became a much-celebrated heroine in the German Democratic Republic, and every major city had a street named after her. Even today, Clara Zetkin's name can still be found on the maps of the former lands of the GDR.[7]

Works

Posthumous honors

- Zetkin was memorialized on the ten mark banknote and twenty mark coin of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) (East Germany).

- After 1949, every major city in the GDR had a street named after her.

- In 1954, the GDR established the Clara Zetkin Medal (Clara-Zetkin-Medaille).

- In 1955, the city council of Leipzig established a new recreation area near the city center called "Clara-Zetkin-Park"[20]

- In 1967, a statue of Clara Zetkin, sculpted by GDR artist Walter Arnold, was erected in Johannapark in Leipzig in commemoration of her 110th birthday.[21]

- In 1987, the GDR issued a stamp with her picture.

References

- ↑ Die Gleichheit had appeared in early 1890 as Die Arbeiterin (The Worker), a successor to the short-lived Die Staatsbürgerin (The Citizeness) founded by Gertrud Guillaume-Schack and banned in June 1886. Zetkin renamed the paper Die Gleichheit when she took over.[9]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Zetkin, Clara * 5.7.1857, † 20.6.1933: Biographische Angaben aus dem Handbuch der Deutschen Kommunisten". Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur: Biographische Datenbanken. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ Clara Zetkin | bpb

- ↑ Gilbert Badia, Clara Zetkin: Feministe Sans Frontieres (Paris: Les Editions Ouvrieres 1993).

- 1 2 Young, James D. (1988). Socialism since 1889: a biographical history. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 169. ISBN 0-389-20813-2.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of World Biography: Vitoria-Zworykin. Gale Research. 1998. p. 504. ISBN 0-7876-2556-6.

- ↑ Zetkin, Klara; Philip Sheldon Foner (1984). Clara Zetkin, selected writings. International Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 0-7178-0620-0.

- 1 2 3 Clara Zetkin biography from the University of Leipzig (in German): http://research.uni-leipzig.de/agintern/frauen/zetkin.htm

- ↑ Clara Zetkin biography at Fembio.org (in German): http://www.fembio.org/biographie.php/frau/biographie/clara-zetkin/

- ↑ Mutert 1996, p. 84.

- 1 2 Temma Kaplan, "On the Socialist Origins of International Women's Day", Feminist Studies, 11/1 (Spring, 1985)

- 1 2 "History of International Women's Day". United Nations. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ↑ Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild, "From West to East: International Women’s Day, the First Decade”, Aspasia: The International Yearbook of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern European Women's and Gender History, vol. 6 (2012): 1-24.

- ↑ "About International Women's Day". Internationalwomensday.com. March 8, 1917. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ↑ "United Nations page on the background of the IWD". Un.org. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ↑ Marilyn Boxer, "Rethinking the Socialist Construction and International Career of the Concept "Bourgeois Feminism" American Historical Review. Feb2007, Vol. 112 Issue 1, p131-158

- ↑ Klara Zetkin, "German Women to Their Sisters in Great Britain" December 1913: https://www.marxists.org/archive/zetkin/1913/12/sisters.htm

- ↑ Timeline of Clara Zetkin's life, at the Lebendiges Museum Online (LEMO): https://www.dhm.de/lemo/biografie/clara-zetkin

- ↑ Marxist Internet Archive Biography: https://www.marxists.org/glossary/people/z/e.htm#zetkin-clara

- ↑ The interview transcript (in English) is available at The Emancipation of Women: From the Writings of V.I. Lenin, interview with Clara Zetkin, International Publishers, on the Marxist Archives

- ↑ Clara-Zetkin-Park - Stadt Leipzig

- ↑ de:Clara-Zetkin-Park (Leipzig)

Sources

- Mutert, Susanne (1996). "Femmes et syndicats en Bavière". Métiers, corporations, syndicalismes (in French). Presses Univ. du Mirail. ISBN 978-2-85816-289-5. Retrieved 2014-11-04.

Further reading

- Full works of Clara Zetkin available (in English) at the Marxist Internet archive: https://www.marxists.org/archive/zetkin/

- Full works of Clara Zetkin available (in German) at the Marxist Internet archive: https://www.marxists.org/deutsch/archiv/zetkin/

- Timeline of Clara Zetkin's life (in German), at the Lebendiges Museum Online (LEMO): https://www.dhm.de/lemo/biografie/clara-zetkin

- Clara Zetkin, Clara Zetkin: Selected Writing, 1991, ISBN 0-7178-0611-1.

- Dorothea Reetz, Clara Zetkin as a Socialist Speaker, Intl. Pub, 1987, ISBN 0-7178-0649-9.

- Gilbert Badia, Clara Zetkin: Feministe Sans Frontieres (Paris: Les Editions Ouvrieres 1993).

- Luise Dornemann, Clara Zetkin: Leben und Wirken, Dietz; 9., uberarbeitete Aufl edition (1989), ISBN 978-3320012281

- Karen Honeycutt, "Clara Zetkin: A left-wing socialist and feminist in Wilhelmian Germany," Columbia University, 1975

- Clara Zetkin biography at FemBio.org (in German): http://www.fembio.org/biographie.php/frau/biographie/clara-zetkin/

- Clara Zetkin biography from the University of Leipzig (in German): http://research.uni-leipzig.de/agintern/frauen/zetkin.htm

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clara Zetkin. |

- Clara Zetkin at Spartacus Educational (biography, extracts)

- Zetkin at marxists.org (biography, some writings, links)