Clare Camp

Within the boundaries of Clare Parish lies what appears to be an ancient camp, an earthwork enclosure known variously as Erbury, Clare Camp or the Anglo-Roman fort (OS TL768458), at the north end of the town, just to the west of Bridewell Street. The name Erbury is first seen in an inquest and land valuation in 1295, referring to a house, the land around it and a garden. This seemed to be part of the largest and most profitable pasture land in the area, lying outside the town and forming a part of Clare Manor.[1] Erbury means 'earthern fort' from Old English. Bury is a common placename across Britain and refers to a fortified place: it turns up in various guises across Western Europe: borough, burgh, bourg, burg.

Clare and its manor had been owned by a Saxon thane, Aluric (or Aelfric), son of Wisgar (or Withgar), according to the Domesday Book. He was one of the king's thanes of East Anglia and administered the lands on behalf of Emma of Normandy, Canute's wife. Her great-nephew was William the Conqueror.[2]

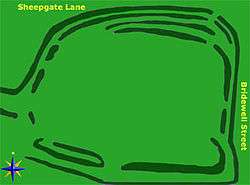

The site is D-shaped, enclosing an area of 12 acres (2.9 hectares). The straightest side is in the south, running roughly west to east. The north side is most complete, with an inner rampart 9 ft high and counterscarps 12 and 14 ft high.[3] With its double ditches it is one of the most impressive of its kind in Suffolk, only slightly smaller than Burgh Castle.

Origin of the camp

Its origin has been disputed. Though it resembles the structure of an Iron Age hillfort, its location is not typical: there is rising ground to the west and north. It is simply not on a hill. To the east there would have been marshy ground and water-meadows – from the various streams feeding the Stour, now drained and channelled. It may have had a wooden palisade on the inner and highest ring of earthworks.

The sign outside the Ancient House calls it an Anglo-Roman Camp. Yet no Roman traces have been found on the site, in fact, very few throughout Clare, though the Via Devana probably ran through the area and there were significant Roman settlements in Wixoe and Long Melford. The whole shape bears little resemblance to other Roman fortified structures.

However recent evidence points to an Iron Age origin. In 1993 a field survey and magnometric scan examining the medieval structures within the site revealed that the ramparts were the oldest part of the site and that there was the possibility of an entrance on the east (follow the footpath from Bridewell Street). The stratigraphy of the earthworks confirms the likelihood of a prehistoric origin.[4] In 2009 during a rebuilding programme at the nearby Clare Primary School, postholes of a late Bronze/Early Iron Age structure were located, with an associated ring ditch.[5] Only a proper excavation will reveal a more accurate date of construction.

In the Iron Age Erbury was a frontier location on the outer borders of the Trinovantes territory, just south of the Iceni heartland. Erbury would also have been under threat from the expansionary ambitions of the Catuvellauni from their base in modern day Hertfordshire, particularly under the rule of King Cunobeline (Shakespeare's Cymbeline) from circa 5 BC to 43 AD. Erbury could have been a fortified settlement rather than a fort, and probably marks the first permanent settlement in the Upper Stour valley. Belgic and local coins from this period have been found across the area.[6] By the time the Romans invaded for the second time, hillforts were out of fashion – the tribes knew they were of little use against the legions.

Medieval period

The field survey of 1993 revealed a group of structures in the southwest corner, including two well-preserved, one 32m long by 12m wide, the other 40m long by 14.5m wide.[4] These seem to be the sleeper walls of timber-frame buildings typical of the area, a complex that would include a barn, stables and even a farmhouse, with courtyards or gardens.[4] A dovecote is mentioned in one record. There is the possibility of fish-ponds along with at least one natural spring. In the medieval period, Clare Castle flourished as the administrative centre of the de Clares. Erbury seems to have been the manor's home farm providing the bulk of basic foodstuffs from the pastures and meadows plus fruit from the orchards of pear, apple and cherry, noted in the castle records. The main farmhouse was considered not worth repairing in 1368. Quarrying of flint seems to have occurred – this seems to coincide with the gradual abandonment of the castle.

The Common

Between 1515 and 1534 the remaining lands of the Manor of Erbury were granted for the benefit of the poor of Clare by Katherine of Aragon; this area includes the camp, identified as Erbury Garden, and extends westward from Bridewell Street for 1.5 km. In 1580, the land was being used to finance local poor relief. In 1609 James I granted the lands to Sir Henry Bromley, a local magnate; enclosure acts were beginning to expropriate common lands. After a long legal action, the land was returned to Clare, but the heavy costs meant it was leased at commercial rates, leaving little for the poor. By the 1860s most of the tenants were tradesmen; the annual distribution of money benefitted them, rather than the poor. In 1874 the Trustees allowed the vicar to fence off part of the common: he wanted to extend his garden rather than graze his allotment of two cows. There was a public outcry. The fences were torn down. The police were called. A march of 100 women and children took place, singing the Clare Common Ballad.[7] Twice more the fences were torn down. After a public inquiry and change of trustees, all the land was returned to the benefit of the poor.[8]

In 1723 two cottages were moved from Clare and erected on the lower common as pest houses for bubonic plague and smallpox. When neither disease was present, the cottages were available for rent; during an outbreak, the tenant was moved elsewhere and his rent paid by the church. Both buildings are shown as 'smallpox houses' on the Tithe Map of 1846. The house within the Camp had been demolished by 1884. The second house, just outside the camp, survived until 1960. A postcard of 1916 shows it to have been of typical 17th to 18th century timber framed construction, with a central brick chimney stack.[9]

Today the whole common is Open Access,[10] administered under the title Common Pasture as a charity (Registered with the Charity Commission No 206513); the managing trust is known as Clare Combined Charities (Web page on Clare Town Council website). The lower common is leased as cow pasture from Easter to November, for a maximum of 20 cattle.

Local geography

To the north of the site runs Sheepgate Lane. This is a deeply recessed trackway following the outer curve of the camp, probably a drove road of medieval origin.[11] Note a similar deep lane south of Clare known as Long Lane,[12] typical of a drover trackway, underlining Clare's significance as a market town.

To the south of the site is Common Street. Prior to the 17th century this was a large quarry, supplying flint and gravel to much of the more substantial buildings in Clare: the Church and Castle.[4]

References

- ↑ Gladys Thornton: A History of Clare, Suffolk, Heffer 1928 pp17-20

- ↑ The Archaeological journal, Volume V p230

- ↑ Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Suffolk, 1974, Penguin 2nd ed. p169, ISBN 0-14-071020-5

- 1 2 3 4 Clare Camp: An Archaeological Survey by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, September to October 1993, Archive Report, p15

- ↑ Suffolk Institute of Archaeology & History, Vol XLII Part 2

- ↑ Google map of archaeological finds]

- ↑ Transcribed by Walter A Perry, The Common at Clare 1870, booklet 2002, Clare Ancient House Museum - Text:

- ↑ David Hatton, Clare, Suffolk, an account of historical features of the town, its Priory and its Parish Church, 2006 ISBN 0-9524242-3-1

- ↑ English Heritage, Pastscape 906557 Pastscape page

- ↑ Natural England map

- ↑ English Heritage: Pastscape 906582 Pastscape page

- ↑ OS TL775425 to TL773448