Claudio Monteverdi

.jpg)

_Cappella_dei_milanesi-_tomb_of_Claudio_Monteverdi.jpg)

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (Italian: [ˈklaudjo monteˈverdi]; 15 May 1567 (baptized) – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, gambist, singer, and Catholic priest.[2]

Monteverdi is considered a crucial transitional figure between the Renaissance and the Baroque periods of music history.[3] While he worked extensively in the tradition of earlier Renaissance polyphony, such as in his madrigals, he also made great developments in form and melody and began employing the basso continuo technique, distinctive of the Baroque.[4] Monteverdi wrote one of the earliest operas, L'Orfeo, which is the earliest surviving opera still regularly performed.

Life

Claudio Monteverdi was born in 1567 in Cremona, Duchy of Milan (now Lombardy, Italy). His father was Baldassare Monteverdi, a doctor, apothecary and amateur surgeon.[6] He was the oldest of five children.[7] During his childhood, he was taught by Marc'Antonio Ingegneri,[8] the maestro di cappella at the Cathedral of Cremona.[9] The Maestro’s job was to conduct important worship services in accordance with the liturgy of the Catholic Church.[10] Monteverdi learned about music as a member of the cathedral choir.[11] He also studied at the University of Cremona.[11] His first music was written for publication, including some motets and sacred madrigals, in 1582 and 1583.[12] His first five publications were: Sacrae cantiunculae, 1582 (a collection of miniature motets); Madrigali Spirituali, 1583 (a volume of which only the bass partbook is extant); Canzonette a tre voci, 1584 (a collection of three-voice canzonettes); and the five-part madrigals Book I, 1587, and Book II, 1590.[13] He worked at the court of Vincenzo I of Gonzaga in Mantua as a vocalist and viol player, then as music director.[14][15] In 1602, he was working as the court conductor[14] and Vincenzo appointed him master of music on the death of Benedetto Pallavicino.

In 1599 Monteverdi married the court singer Claudia Cattaneo,[17] who died in September 1607.[18] They had two sons (Francesco and Massimilino) and a daughter (Leonora). Another daughter died shortly after birth.[19] In 1610 he moved to Rome, arriving in secret, hoping to present his music to Pope Paul V. His Vespers were printed the same year, but his planned meeting with the Pope never took place.

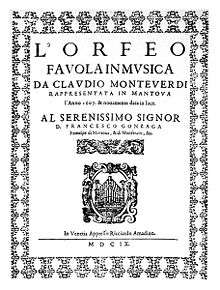

In 1612 Vincenzo died and was succeeded by his eldest son Francesco. Heavily in debt, due to the profligacy of his father, Francesco sacked Monteverdi and he spent a year in Mantua without any paid employment. His 1607 opera L'Orfeo was dedicated to Francesco. The title page of the opera bears the dedication "Al serenissimo signor D. Francesco Gonzaga, Prencipe di Mantoua, & di Monferato, &c."

By 1613, he had moved to San Marco in Venice where, as conductor,[20] he quickly restored the musical standard of both the choir and the instrumentalists. The musical standard had declined due to the financial mismanagement of his predecessor, Giulio Cesare Martinengo.[20] The managers of the basilica were relieved to have such a distinguished musician in charge, as the music had been declining since the death of Giovanni Croce in 1609.[20]

In 1632, he became a priest.[21] During the last years of his life, when he was often ill, he composed his two last masterpieces: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (The Return of Ulysses, 1641), and the historic opera L'incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea, 1642), based on the life of the Roman emperor Nero.[22] L'incoronazione especially is considered a culminating point of Monteverdi's work. It contains tragic, romantic, and comic scenes (a new development in opera), a more realistic portrayal of the characters, and warmer melodies than previously heard.[23] It requires a smaller orchestra, and has a less prominent role for the choir. For a long period of time, Monteverdi's operas were merely regarded as a historical or musical interest. Since the 1960s, The Coronation of Poppea has re-entered the repertoire of major opera companies worldwide.

Monteverdi died, aged 76, in Venice on 29 November 1643[14] and was buried at the church of the Frari.[24]

Works

Monteverdi's works are split into three categories: madrigals, operas, and church-music.[25]

Madrigals

|

Cor mio mentre vi miro

Non si levav'ancor

Lamento della Ninfa from Madrigali Guerrieri et Amorosi

Live recording |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Until the age of forty, Monteverdi worked primarily on madrigals, composing a total of nine books. It took Monteverdi about four years to finish his first book of twenty-one madrigals for five voices.[12] As a whole, the first eight books of madrigals show the enormous development from Renaissance polyphonic music to the monodic style typical of Baroque music.

The titles of his Madrigal books are:

- Book 1, 1587: Madrigali a cinque voci[11]

- Book 2, 1590: Il secondo libro de madrigali a cinque voci

- Book 3, 1592: Il terzo libro de madrigali a cinque voci[13]

- Book 4, 1603: Il quarto libro de madrigali a cinque voci[13]

- Book 5, 1605: Il quinto libro de madrigali a cinque voci[13]

- Book 6, 1614: Il sesto libro de madrigali a cinque voci[26]

- Book 7, 1619: Concerto. Settimo libro di madrigali[27]

- Book 8, 1638: Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosi con alcuni opuscoli in genere rappresentativo, che saranno per brevi episodi fra i canti senza gesto.[28]

- Book 9, 1651: Madrigali e canzonette a due e tre voci[28]

The Fifth Madrigal Book

|

Cruda Amarilli

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The Fifth Book of Madrigals shows the shift from the late Renaissance style of music to the early Baroque.[29] The Quinto Libro (Fifth Book), published in 1605, was at the heart of the controversy between Monteverdi and Giovanni Artusi. Artusi attacked the "crudities" and "license" of the modern style of composing, centering his attacks on madrigals (including Cruda Amarilli, composed around 1600) (See Fabbri, Monteverdi, p. 60) from the fourth book.[12] Monteverdi made his reply in the introduction to the fifth book, with a proposal of the division of musical practice into two streams, which he called prima pratica, and seconda pratica. Prima pratica was described as the previous polyphonic ideal of the sixteenth century, with flowing strict counterpoint, prepared dissonance, and equality of voices. Seconda pratica used much freer counterpoint with an increasing hierarchy of voices, emphasizing soprano and bass. In Prima pratica the harmony controls the words.[11] In seconda pratica the words should be in control of the harmonies.[11] This represented a move towards the new style of monody. The introduction of continuo in many of the madrigals was a further self-consciously modern feature.[19] In addition, the fifth book showed the beginnings of conscious functional tonality.

The Eighth Madrigal Book

While in Venice, Monteverdi also finished his sixth (1614), seventh (1619), and eighth (1638) books of madrigals. The eighth is the largest, containing works written over a thirty-year period. Originally the work was to be dedicated to Ferdinand II, but because of his ill health, his son was made king in December 1636. When the work was first published in 1638 Monteverdi rededicated it to the new King Ferdinand III.[30] The eighth book includes the so-called Madrigali dei guerrieri et amorosi (Madrigals of War and Love).[26]

The important preface of Monteverdi’s eighth madrigal book seems to be connected with his seconda pratica. He claims to have invented a new "agitated" style (genere concitato, later called stile concitato). [31]

The book is divided into sections of War and Love each containing madrigals, a piece in dramatic form (genere rappresentativo), and a ballet. In the Madrigals of War, Monteverdi has organized poetry that describes the pursuits of love through the allegory of war; the hunt for love, and the battle to find love. In the second half of the book, the Madrigals of Love, Monteverdi organized poetry that describes the unhappiness of being in love, unfaithfulness, and ungrateful lovers who feel no shame. In his previous madrigal collections, Monteverdi usually set poetry from one or two poets he was in contact with through the court where he was employed. The Madrigals of War and Love represent an overview of the poets he has dealt with throughout his life; the classical poetry of Petrarch, poetry by his contemporaries (Tasso, Guarini, Marino, Rinuccini, Testi and Strozzi), or anonymous poets who Monteverdi found and adapted to his needs.

Madrigals of War

- Altri canti d’Amor tenero arciero (Let others sing of Love, the tender archer) anonymous sonnet

- is preceded by a sinfonia introduction that is written for two violins and four viols. The madrigal that follows serves as an introduction to the first half of the collection and as a dedication to Ferdinand III.

- Hor che’l ciel e la terra e’l vento tace (Now that the sky, earth and wind are silent) Sonnet by Petrarch,

- is the first significant poetic work of the collection in which Monteverdi splits into two sections. In the first section, his poetry introduces the idea of the wars of love, in which he yearns for someone to love him.

- "War is my condition full of anger and grief, and only when thinking of her do I find some peace."

- In the second section, "Thus from a single bright and living fountain" (Cosi sol d’una chiara fonte viva) the symbolism of war continues:

- "One hand alone cures me and wounds me. And, because my suffering never reaches its limits, a thousand times daily I die, and a thousand I am born, so far am I from my salvation."

- is the first significant poetic work of the collection in which Monteverdi splits into two sections. In the first section, his poetry introduces the idea of the wars of love, in which he yearns for someone to love him.

- Gira il nemico insidioso Amore (The insidious enemy, Love, circles the citadel of my heart) canzonetta by Strozzi

- Se vittorie si belle han le guerre d’amore (If love’s wars have such beautiful victories) madrigal by Testi

- Armato il cor d’adamantina fede (My heart armed with adamantine faith) madrigal by Rinuccini

- Ogni amante e guerrier: nel suo gran regno (Every lover is a warrior: in his great kingdom) madrigal by Rinuccini

- Ardo, avvampo, mi struggo, ardo: accorrete (I burn, I blaze, I am consumed, I burn; come running) anonymous sonnet

- Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda (The Combat of Tancredi and Clorinda) from Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, Canto XII

- was originally composed and performed at the home of Girolamo Mocenigo (1624)[32] and includes the dramatic scene in which the orchestra and voices form two separate entities, acting as counterparts. Most likely Monteverdi was inspired to try this arrangement because of the two opposite balconies in San Marco. What made this composition also stand out is that it is the first time Monteverdi used string tremolo (fast repetition of the same tone) and pizzicato (plucking strings with fingers) for special effect in dramatic scenes.

- Introduzione al ballo e ballo: Volgendo il ciel (Introduction to the ballet, and ballet) sonnet by Rinuccini

Madrigals of Love

- Altri canti di Marte e di sua schiera (Let others sing of Mars and of his host) sonnet by Marino

- the parallel work to Altri canti d amor, it serves as an introduction to the second half of the collection. Like its counterpart, it, too, is preceded by an instrumental sinfonia and contains a dedication to Ferdinand III.

- Vago augelletto che cantando vai (Lovely little bird, who are you singing about?) sonnet by Petrarch

- Mentre vaga angioletta (While a charming, angelic girl attracts every wellborn soul with her singing) madrigal by Guarini

- Ardo e scoprir, ahi lasso, io non ardisco (I burn and, alas, I do not have the courage to reveal that burning which I bear hidden in my breast) anonymous madrigal

- O sia tranquillo il mare o pien d’orgoglio (Whether the sea be still or swelled with pride) anonymous sonnet

- Ninfa che, scalza il piede e sciolto il crine (Nymph, who with bare feet and hair undone) anonymous madrigal

- Dolcissimo uscignolo (Sweetest nightingale) madrigal by Guarini

- Chi vol haver felice e lieto il core (Whoever wishes to have a happy joyful heart) madrigal by Guarini

- Non Havea Febo ancora: Lamento della ninfa (Phoebus had not yet: The Lament of the Nymph) canzonetta by Rinuccini

- Perché te'n fuggi, o Fillide? (Why do you run away, Phyllis?) anonymous madrigal

- Non partir, ritrosetta (Do not depart, maiden averse to love) anonymous canzonetta

- Su, su, su, pastorelli vezzosi (Come, come, come, charming shepherd lads) anonymous canzonetta

- Il ballo delle ingrate (Entrance and Final ballet of the Ungrateful Women)

- The Ballet of the Ungrateful Women was originally composed for the 1608 wedding of Francesco Gonzaga and was revived in 1628 for a performance in Vienna.[33]

The Ninth Madrigal Book

The ninth book of madrigals, published posthumously in 1651,[11] contains lighter pieces such as canzonettas which were probably composed throughout Monteverdi's lifetime representing both styles.

Operas

Monteverdi was often ill during the last years of his life. During this time, he composed his two last masterpieces: Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (The Return of Ulysses, 1640), and the historic opera, L'incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea, 1642),[34] based on an episode in the life of the Roman emperor Nero. The libretto for Il ritorno d'Ulisse was written by Giacomo Badoarro and for L'incoronazione di Poppea by Giovanni Busenello.[35]

L'Orfeo

Monteverdi composed at least eighteen operas, but only L'Orfeo, Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, L'incoronazione di Poppea, and the famous aria, Lamento, from his second opera L'Arianna have survived. From monody (with melodic lines, intelligible text and placid accompanying music), it was a logical step for Monteverdi to begin composing opera. In 1607, his first opera, L'Orfeo, premiered in Mantua.[12] L'Orfeo was not the first opera, but it was the first mature opera, or one that realized all of its potential.[36] It was normal at that time for composers to create works on demand for special occasions, and this piece was part of the ducal celebrations of carnival.[36] (Monteverdi was later to write for the first opera houses supported by ticket sales which opened in Venice). L'Orfeo has dramatic power and lively orchestration. L'Orfeo is arguably the first example of a composer assigning specific instruments to parts in operas. It is also one of the first large compositions for which the exact instrumentation of the premiere is still known.[37] The plot is described in vivid musical pictures and the melodies are linear and clear. With this opera, Monteverdi created an entirely new style of music, the dramma per la musica or musical drama.

L'Arianna

L'Arianna was the second opera written by Monteverdi. It is one of the most influential and famous specimens of early Baroque opera. It was first performed in Mantua in 1608.[19] Its subject matter was the ancient Greek legend of Ariadne and Theseus. Italian composer Ottorino Respighi famously orchestrated the "Lamento di Arianna" in 1908, and the work was premiered by the Berlin Philharmonic the same year under conductor Arthur Nikisch. The manuscript was restored and published as a critical edition in 2013 by Italian composer/conductor Salvatore Di Vittorio under publisher Edizioni Panastudio. A later completion of the "Lamento" from L'Arianna by Scottish composer Gareth Wilson (b. 1976) was performed at King's College, London University on 29 November 2013, the 370th anniversary of Monteverdi's death.

Sacred music

Vespro della Beata Vergine

|

Deus in adiutorium, from Vespro della Beata Vergine

Laudate pueri, from Vespro della Beata Vergine

|

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Monteverdi's first church music publication was the archaic Mass In illo tempore to which the Vesper Psalms of 1610 were added.[13] The Vesper Psalms of 1610 are also one of the best examples of early repetition and contrast, with many of the parts having a clear ritornello. The published work is on a very grand scale and there has been some controversy as to whether all the movements were intended to be performed in a single service. However, there are various indications of internal unity. In its scope, it foreshadows such summits of Baroque music as Handel's Messiah, and J.S. Bach's St Matthew Passion. Each part (there are twenty-five in total) is fully developed in both a musical and dramatic sense – the instrumental textures are used to precise dramatic and emotional effect, in a way that had not been seen before.

Other sacred works

- Messa in illo tempore (1610)

- Mass of Thanksgiving (1631)[38]

- Messa a 4 da cappella (1641) (also: Missa in F), part of Selva morale e spirituale

- Messa a 4 v. et salmi a 1–8 v. e parte da cappella & con le litanie della B.V. (Mass for four voices, and Psalms ...) (published posthumously, 1650)

Other works

- Scherzi Musicali, Cioè Arie, et Madrigali in stil recitativo, con una Ciaccona a 1 et 2 voci (Zefiro torna) (1632)

Sacred contrafacta

In 1607, Aquilino Coppini published in Milan his "Musica tolta da i Madrigali di Claudio Monteverde, e d'altri autori ... e fatta spirituale" for 5 and 6 voices, in which many of Monteverdi's madrigals (especially from the third, fourth and fifth books) are presented with the original secular texts replaced with sacred Latin contrafacta carefully prepared by Coppini in order to fit the music in every aspect.

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 "Mehr dazu", information about the identification of Claudio Monteverdi as the subject of Bernardo Strozzi's portrait at the Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/biography/Claudio-Monteverdi

- ↑ Halsey, William D., ed. Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. 16. New York: MacMillan Educational Company, 1991.

- ↑ Ringer, Mark. Opera's First Master: The Musical Dramas of Claudio Monteverdi. Canada: Amadeus Press, 2006.

- ↑ "Portrait of a Musician" at the Ashmolean Museum website.

- ↑ Halsey, William D., ed. Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. 16 New York: MacMillan Educational Company, 1991.

- ↑ Redlich, H. F. Claudio Monteverdi: Life and Work. London: Oxford University Press, 1952, .

- ↑ Redlich, H. F. Claudio Monteverdi: Life and Work. London: Oxford University Press, 1952.

- ↑ Schrade, Leo. Monteverdi: Creator of Modern Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1950, .

- ↑ Whenham, John, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schrade, Leo. Monteverdi: Creator of Modern Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1950, .

- 1 2 3 4 Schrade, Leo. Monteverdi: Creator of Modern Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1950.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Halsey, William D., ed. Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. 16. New York: MacMillan Educational Company, 1991.

- 1 2 3 Cayne, Bernard S., ed. Encyclopedia Americana Deluxe Library Edition. Vol. 19. Danbury: Grolier Incorporated, 1990.

- ↑ Roger Kamien, An Appreciation of Music, 4th brief edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2002, .

- ↑ Pamela Askew, "Fetti's 'Portrait of an Actor' Reconsidered", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 120, no. 899 (February 1978), pp. 59-65.

- ↑ Whenham, John, and Richard Wistreich, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- ↑ Whenham, John, and Richard Wistreich, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, 66.

- 1 2 3 Ringer, Mark. Opera's First Master: The Musical Dramas of Claudio Monteverdi. Canada: Amadeus Press, 2006, .

- 1 2 3 Redlich, H. F. Claudio Monteverdi: Life and Work. London: Oxford University Press, 1952, .

- ↑ Marthaler, Benard L., ed. New Catholic Encyclopedia 2nd ed. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2003.

- ↑ Sadie, Stanley, ed. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 2nd ed. London: MacMillan Publishers Limited, 2001.

- ↑ Arnold, Denis, and Nigel Fortune, eds. The New Monteverdi Companion. London: faber and faber, 1985, .

- ↑ Halsey, William D., ed. Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. 16.. New York: MacMillan Educational Company, 1991.

- ↑ Redlich, H. F. Claudio Monteverdi: Life and Work. London: Oxford University, Press, 1952, .

- 1 2 Arnold, Denis. Monteverdi Madrigals. London: Billing and Sons Limited, 1967.

- ↑ Arnold, Denis. Monteverdi Madrigals. London: Billing and Sons Limited, 1967, .

- 1 2 Schrade, Leo. Monteverdi: Creator of Modern Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Company 1950, .

- ↑ Ringer, Mark. Opera's First Master: The Musical Dramas of Claudio Monteverdi. Canada: Amadeus Press, 2006.

- ↑ Denis Arnold and Nigel Fortune, Editors. The New Monteverdi Companion. (Boston: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1985), 233.

- ↑ Gerald Drebes: ‘‘Monteverdis „Kontrastprinzip", die Vorrede zu seinem 8. Madrigalbuch und das „Genere concitato".‘‘ In: ‘‘Musiktheorie‘‘, Jg. 6, 1991, S. 29–42 online:

- ↑ Paolo Fabbri, Monteverdi, translated from the Italian by Tim Carter (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 238–39.

- ↑ Paolo Fabbri, Monteverdi, translated by Tim Carter (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 238–39.

- ↑ Redlich, H. F. Claudio Monteveri: Life and Work. London: Oxford University Press, 1952.

- ↑ Halsey, William D., ed. Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. 16. New York: MacMillan Educational Company 1991.

- 1 2 Whenham, John. Claudio Monteverdi Orfeo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986, .

- ↑ Whenham, John. Claudio Monteverdi Orfeo. Cambridge: Cambrdige University Press, 1986, .

- ↑ Mass of Thanksgiving Gramophone

Cited sources

- Arnold, Denis, and Nigel Fortune (eds.) (1985) The New Monteverdi Companion. London and Boston: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-13148-8.

- Whenham, John, and Richard Wistreich (eds.) (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-87525-0 (cloth) ISBN 0-521-69798-0 (pbk)

Other sources

- Carter, Tim (1992). Music in Late Renaissance and Early Baroque Italy. Amadeus Press, 1992. ISBN 0-931340-53-5

- Leopold, Silke (1991). Monteverdi: Music in Transition. translated from the German by Anne Smith. Oxford & New York: Clarendon Press & Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315248-7.

- Monteverdi, Claudio (1980). The Letters of Claudio Monteverdi. ed. Denis Stevens. London. ISBN 0-521-23591-X.

- Schrade, Leo (1979). Monteverdi. London, Victor Gollancz Ltd. ISBN 0-575-01472-5

- Toft, Robert (2014). With Passionate Voice: Re-Creative Singing in 16th-Century England and Italy. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199382033.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Claudio Monteverdi. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- English translations of Monteverdi's fourth book of madrigals

- Free scores by Claudio Monteverdi in the Open Music Library

- Free scores by Claudio Monteverdi in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Claudio Monteverdi at the International Music Score Library Project

- The Mutopia Project has compositions by Claudio Monteverdi

- Lauda Jerusalem from Vespro della Beata Vergine as interactive hypermedia at the BinAural Collaborative Hypertext

- Video of several works by Monteverdi performed on original instruments by the ensemble Voices of Music using baroque instruments, ornamentation, temperaments, bows, and playing techniques.

- Score and audio files of an arrangement of Monteverdi's 'Si dolce e'l tormento'.

- "Claudio Monteverdi material". BBC Radio 3 archives.

-

"Monteverde, Claudio". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Monteverde, Claudio". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920. - Ilias Chrissochoidis, "The 'Artusi-Monteverdi' Controversy: Background, Content, and Modern Interpretations," British Postgraduate Musicology 6 (2004), online (general introduction suitable for undergraduates).

.jpg)