Codex Basilensis A. N. III. 12

|

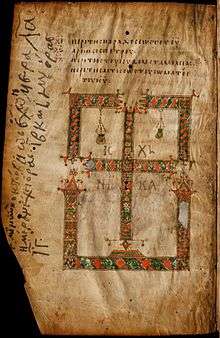

Table of contents to the Gospel of Matthew | |

| Name | Codex Basilensis |

|---|---|

| Sign | Ee |

| Text | Gospels |

| Date | 8th century |

| Script | Greek |

| Found | 1431 |

| Now at | Basel University Library |

| Size | 23 × 16.5 cm (9.1 × 6.5 in) |

| Type | Byzantine text-type |

| Category | V |

| Hand | carefully written |

| Note | member of Family E |

Codex Basilensis, designated by Ee, 07 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering) or ε 55 (von Soden), is a Greek uncial manuscript of the four Gospels, dated paleographically to the 8th century. The codex is located, as its name indicates, in Basel University Library.

The manuscript is lacunose, it has marginalia, and was adapted for liturgical reading. Three leaves of the codex were overwritten by a later hand; these leaves are considered palimpsests.

The text of the codex represents the majority of the text (Byzantine text-type), but a small number of alien readings (non-Byzantine). It contains spurious biblical passages, but they are marked as doubtful within the text. The text of the manuscript has been cited in all critical editions of the Greek New Testament, but it is not high esteemed by scholars.

Description

The text is written in one column per page, with 23 or more lines. The codex contains 318 parchment leaves of size 23 × 16.5 cm (9.1 × 6.5 in), with an almost complete text of the four Gospels.[1][2] The Gospel of Luke contains five small lacunae (1:69-2:4, 3:4-15, 12:58-13:12, 15:8-20, 24:47-end). Three of them were later completed in cursive (1:69-2:4, 12:58-13:12, 15:8-20).[3]

The letters Θ Ε Ο Σ are round, the strokes of Χ Ζ Ξ are not prolonged below the line. It has a regular system of punctuation.[4] The handwriting is similar to that in the Codex Alexandrinus, though not so regular and neat. The initial letters are decorated with green, blue, and vermilion.[5]

Certain disputed passages are marked with an asterisk – signs of the times (Matthew 16:2b-3), Christ agony (Luke 22:43-44), Luke 23:34, Pericope Adulterae (John 8:2-11).[6][7]

It contains tables of the κεφαλαια (tables of contents) before each Gospel and the text is divided according to the κεφαλαια (chapters), the numbers of which are placed in the margins. The chapters are divided into Ammonian Sections with references to the Eusebian Canons (written below Ammonian Section numbers), and the harmony at the foot of the pages,[8] although full references to all parallel texts are given in the margins and the tables are thus superfluous.[3] The initial letters at the beginning sections stand out on the margin as in codices Alexandrinus, Ephraemi Rescriptus.[5]

The codex was bound with the 12th century minuscule codex 2087, which contains portions of the Book of Revelation. Three leaves of the codex are palimpsests (folio 160, 207, 214) – they were overwritten by a later hand.[3] Folio 207 contains a fragment of Ephraem Syrus in Greek, while the texts of folios 160 and 214 are still unidentified.[9]

Text

.jpg)

The Greek text of this codex is representative of the Byzantine textual tradition.[10] According to Kurt and Barbara Aland it agrees with the Byzantine text-type 209 times, and 107 times with both the Byzantine and the original text. Only one reading agrees with the original text against the Byzantine. There are 9 independent or distinctive readings. Aland placed its text in Category V.[1]

It belongs to the textual Family E (the early Byzantine text) and is closely related to the Codex Nanianus, and the Codex Athous Dionysiou.[11][12] Probably it is the oldest manuscript with a pure Byzantine text (with almost a complete text of the Gospels) and it is one of the most important witnesses of the Byzantine text-type.[7]

In Matthew 8:13 it has an interpolation – marked by an asterisk – και υποστρεψας ο εκατονταρχος εις τον οικον αυτου εν αυτη τη ωρα ευρεν τον παιδα υγιαινοντα (and when the centurion returned to the house in that hour, he found the slave well). This reading of the codex is supported by: Codex Sinaiticus, Ephraemi Rescriptus, Codex Campianus, (Petropolitanus Purpureus), Codex Nanianus, Codex Koridethi, (0250), f1, (33, 1241), g1, syrh.[13][14]

- Some textual variants

| Extract | Codex Basilensis | Textus Receptus | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mark 5:9 | απεκριθη λεγων (answered and said) | λεγει αυτω (said to him) | [15] |

| John 1:22 | βηθανια (Bethania) | βηθαραβα (Bethabara) | [16] |

| John 1:28 | συ (you) | τις (who) | [17] |

| John 4:1 | ο Κυριος (the Lord) | ο Ιησουυς (Jesus) | [18] |

| John 5:44 | αλληλων (one another) | ανθρωπων (men) | [19] |

| John 8:9 | οι δε ακουσαντες και υπο της συνειδησεως ελεγχομενοι εξερχοντο εις καθ εις (they heard it, and remorse took them, they went away, one by one) | οι δε ακουσαντες εξερχοντο εις καθ εις (they heard it, they went away, one by one) | [20] |

| John 10:8 | ηλθων (came) | ηλθων προ εμου (came before me) | [21] |

History

Dating

It is generally accepted among palaegraphers that the manuscript was written in the 8th century (Scrivener, Gregory,[3] Nestle, Aland,[1] Metzger[10]). Dean Burgon proposed the 7th century (because of the shape of the letters), but the names of Feasts days with their proper lessons and other liturgical markings have been inserted by a later hand.[5] Scrivener dated it to the middle of the 8th century.[8] Scrivener stated that from the shape of the most of the letters (e.g. pi, delta, xi), it might be judged of even earlier date.[5] According to Guglielmo Cavallo it was written in the early 8th century.[22]

According to Cataldi Palau it was written later in the 9th century. From the palaeographical point of view it looks older, but the regularity of the accentuation and the abundant colourful decoration are uncharacteristic of the 8th century. The number of errors is remarkably small. According to Palau it was copied by a non-Greek, probably Latin scribe, in 9th century Italy. The Italian location had a strong Byzantine influence.[23]

Location

It probably was brought to Basel by Cardinal Ragusio (1380–1443),[3] who may have acquired it in Constantinople[8] when he attended the Council of Florence in 1431. It might have been a present from the Byzantine emperor. In time of that council several other manuscripts came to Europe from Byzantium: Codex Basiliensis A.N.IV.2, Minuscule 10, and probably Codex Vaticanus. In 1559 it was presented to the monastery of the Preaching Friars.[3] In the same year it was transferred to Basel University Library (A. N. III. 12), in Basel (Switzerland), where it is currently housed.[1][2] Formerly it was held under the shelf-number B VI. 21, then lately K IV. 35.[24]

Use in the Greek New Testament editions

The codex was available to Erasmus for his translation of the New Testament in Basel, but he never used it. The text of the manuscript was collated by Johann Jakob Wettstein[25] and the manuscript was used by John Mill in his edition of the Greek New Testament. It has been cited in printed editions of the Greek New Testament since the 18th century.[26]

The manuscript is cited in all critical editions of the Greek New Testament (UBS3,[27] UBS4,[28] NA26,[29] NA27). It is rarely cited in NA27, as a witnesses of the third order.[30]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Aland, Kurt; Barbara Aland (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- 1 2 "Online copy of the MS". Münster: Institute for New Testament Textual Research. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gregory, Caspar René (1900). Textkritik des Neuen Testaments. 1. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung. p. 48.

- ↑ J. L. Hug (1836). Introduction to the New Testament. D. Fosdick (trans.). Andover. p. 174.

- 1 2 3 4 Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. 1 (4th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. 132.

- ↑ Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. 1 (4th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. 133.

- 1 2 Robert Waltz, Codex Basilensis E (07): at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism

- 1 2 3 Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. 1 (4th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. 131.

- ↑ Palau, A. C., “A Little Known Manuscript of the Gospels in: ‘Maiuscola biblica’: Basil. Gr A. N. III. 12,” Byzantion 74 (2004): 463-516.

- 1 2 Metzger, Bruce M.; Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration (4 ed.). New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-19-516122-9.

- ↑ Russell Champlin, Family E and Its Allies in Matthew (Studies and Documents, XXIII; Salt Lake City, UT, 1967).

- ↑ J. Greelings, Family E and Its Allies in Mark (Studies and Documents, XXXI; Salt Lake City, UT, 1968).

- ↑ Eberhard Nestle, Erwin Nestle, Barbara Aland and Kurt Aland (eds), Novum Testamentum Graece, 26th edition, (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1991), p. 18.

- ↑ Tischendorf, C. v., Editio octava critica maior, p. 37.

- ↑ Eberhard Nestle, Erwin Nestle, Barbara Aland and Kurt Aland (eds), Novum Testamentum Graece, 26th edition, (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1991), p. 102.

- ↑ The Gospel According to John in the Byzantine Tradition (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2007), s. 6.

- ↑ The Gospel According to John in the Byzantine Tradition (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2007), s. 5.

- ↑ The Gospel According to John in the Byzantine Tradition (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2007), s. 30.

- ↑ The Gospel According to John in the Byzantine Tradition (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2007), s. 55.

- ↑ The Greek New Testament, ed. K. Aland, A. Black, C. M. Martini, B. M. Metzger, and A. Wikgren, in cooperation with INTF, United Bible Societies, 3rd edition, (Stuttgart 1983), p. 357.

- ↑ The Gospel According to John in the Byzantine Tradition (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2007), s. 133.

- ↑ Guglielmo Cavallo: Ricerche sulla maiuscola biblica, Florenz 1967.

- ↑ A. Cataldi Palau, “A Little Known Manuscript of the Gospels in ‘Maiuscola biblica’: Basil. Gr A. N. III. 12,” Byzantion 74 (2004), p. 506.

- ↑ Tischendorf, C. v. (1859). Novum Testamentum Graece. Editio Septima. Lipsiae. p. CLVIII.

- ↑ Wettstein, Johann Jakob (1751). Novum Testamentum Graecum editionis receptae cum lectionibus variantibus codicum manuscripts (in Latin). 1. Amsterdam: Ex Officina Dommeriana. pp. 38–40. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Aland, K.; Black, M.; C. M. Martini, B. Metzger, A. Wikgren (1983). The Greek New Testament (3 ed.). Stuttgart: United Bible Societies. p. XV. [UBS3]

- ↑ The Greek New Testament, ed. K. Aland, A. Black, C. M. Martini, B. M. Metzger, and A. Wikgren, in cooperation with INTF, United Bible Societies, 3rd edition, (Stuttgart 1983), p. XV.

- ↑ The Greek New Testament, ed. B. Aland, K. Aland, J. Karavidopoulos, C. M. Martini, and B. M. Metzger, in cooperation with INTF, United Bible Societies, 4th revised edition, (United Bible Societies, Stuttgart 2001), p. 11, ISBN 978-3-438-05110-3.

- ↑ Nestle, Eberhard et Erwin; communiter ediderunt: K. Aland, M. Black, C. M. Martini, B. M. Metzger, A. Wikgren (1991). Novum Testamentum Graece (26 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. pp. 12*.

- ↑ Nestle, Eberhard et Erwin; communiter ediderunt: B. et K. Aland, J. Karavidopoulos, C. M. Martini, B. M. Metzger (2001). Novum Testamentum Graece (27 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. pp. 58*–59*.

Further reading

- Russell Champlin, Family E and Its Allies in Matthew (Studies and Documents, XXIII; Salt Lake City, UT, 1967).

- J. Greelings, Family E and Its Allies in Mark (Studies and Documents, XXXI; Salt Lake City, UT, 1968).

- J. Greelings, Family E and Its Allies in Luke (Studies and Documents, XXXV; Salt Lake City, UT, 1968).

- F. Wisse, Family E and the Profile Method, Biblica 51, (1970), pp. 67–75.

- Annaclara Cataldi Palau, “A Little Known Manuscript of the Gospels in ‘Maiuscola biblica’: Basil. Gr A. N. III. 12”, Byzantion 74 (2004): 463-516.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Codex Basilensis. |

- Robert Waltz, Codex Basilensis E (07): at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism.

- "Online copy of the MS". Münster: Institute for New Testament Textual Research. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

.jpg)