Colchester Castle

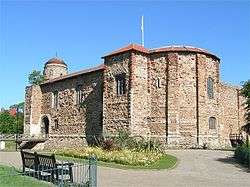

Colchester Castle in Colchester, Essex, England, is an example of a largely complete Norman castle. It is a Grade I listed building.

Construction

At one and a half times the size of the Tower of London's White Tower,[1] Colchester's keep (152 by 112 feet (46 m × 34 m)) is the largest ever built in Britain and the largest surviving example in Europe.[2][3][4] There has always been debate as to the original height of the castle. It has been suggested that the keep was at one time four storeys high, though for a number of reasons, including the peaceful region of the castle and the lack of local stone, it is now thought that it had only two or three.[5] The castle is built on the foundations (or the podium) of the earlier Roman temple of Claudius (built between AD 54–60).[5] These foundations, with their massive vaults, have since been uncovered and can be viewed today on a castle tour.

The castle was ordered by William the Conqueror and designed by Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester. Building began between 1069 and 1076 under the supervision of Eudo Dapifer, who became the castle's steward on its completion. Building stopped in 1080 because of a threat of Viking invasion, but the castle was completed by around 1100. Many materials, such as Roman brick and clay taken from the Roman town, were used in the building and these can easily be seen. Scaffolding pole holes and garderobes can still be seen in the structure.

Later history

In 1215, the castle was besieged and eventually captured by King John, during the First Barons' War.

The castle has had various uses since it ceased to be a royal castle. It has been a county prison, where in 1645 the self-styled Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins interrogated and imprisoned suspected witches. In 1648, during the Second English Civil War, the Royalist leaders Sir Charles Lucas and Sir George Lisle were executed just to the rear of the castle. Local legend has it that grass will not grow on the spot on which they fell. A small obelisk now marks the point. In 1656 the Quaker James Parnell was martyred there.

In 1650 a Parliament Survey condemned the building and valued the stone at five pounds.[6] In 1683 an ironmonger, John Wheely, was licensed to pull it all down - presumably to use as building material in the town. After "great devastations" in which much of the upper structure was demolished using screws and gunpowder, he gave up when the operation became unprofitable.[7]

In 1727 the castle was bought by Mary Webster for her daughter Sarah, who was married to Charles Gray, the Member of Parliament for Colchester. To begin with, Gray leased out the keep to a local grain merchant and the east side was leased out to the county as a gaol. In the late 1740s Gray restored parts of the building, in particular the south front. He created a private park around the ruin and his summer house (perched on the old Norman castle earthworks, in the shape of a Roman temple) can still be seen. He also added a library with large windows and a cupola on the south-east tower, which was completed in 1760. On Gray's death in 1782, the castle passed to his step-grandson, James Round, who continued the restoration work.[8]

The part of the castle under the chapel remained in use as a gaol, which was enlarged in 1801. A long serving gaoler called John Smith lived on site with his family. His daughter Mary Ann Smith was born there in 1777 and lived her whole life in the castle, becoming the librarian until her death in 1852. She is believed to have planted the sycamore tree which is still growing on top of the southeast tower, either to celebrate the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 or to mark her father's death in the same year.[9]

Between 1920 and 1922, the Castle and the associated parkland were bought by the Borough of Colchester using a large donation from Weetman Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray, a wealthy industrialist who had been the town's Member of Parliament. The Park is split into the Upper and Lower Castle Parks. A museum of artefacts owned by the borough had been on display at the castle since 1860, and the roofing over of the keep in the mid-1930s allowed for a considerable expansion.[10]

Between January 2013 and May 2014 the castle museum underwent extensive refurbishment costing £4.2 million. The programme of work improved and updated the displays with the latest research into the castle's history, and supported the repair of the roof.[11]

Ownership

The later inheritance of the castle and its grounds is illustrated below. Only those greyed out did not at some time own the building. Though Charles Gray Round died before the area was sold to the corporation of Colchester, his will ensured that it was held in trust with that eventual purpose.

| Mary Webster | John Webster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ralph Creffeild (1) | Sarah Webster | Charles Gray (2) | Mary Wilbraham | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Peter Creffeild | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thamer Creffeild | James Round | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| James Round | Charles Round | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Charles Gray Round | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Creighton 2002, p. 150.

- ↑ Hull 2006, p. 101.

- ↑ Friar 2003, p. 16.

- ↑ Museums Staff 2011, History.

- 1 2 Crummy 2000.

- ↑ ERO T?P 64/25

- ↑ Wheeler 1920, p. 87.

- ↑ Barrass, Lisa; Saunders, Duncan. "Colchester Castle - Appendix F: Timeline for Colchester Castle". sites.google.com/site/colchesterkeep. Retrieved 23/10/2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Barrass, Lisa; Saunders, Duncan. "Colchester Castle - AppendixJ: Miss Smith and her family". sites.google.com/site/colchesterkeep. Retrieved 23/10/2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Colchester Castle Redevelopment - History". www.cimuseums.org.uk. Colchester & Ipswich Museums. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ↑ Burton 2012, p. 17.

References

- Burton, Peter A. (editor) (2012), "Colchester Castle", The Castle Studies Group Bulletin (PDF), 14

- Creighton, Oliver (2002), Castles and Landscapes, Continuum, ISBN 0-8264-5896-3

- Crummy, Philip (December 2000), A Survey of Colchester Castle (PDF), The Colchester Archaeological Trust, retrieved February 2013 Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Friar, Stephen (2003), The Sutton Companion to Castles, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2

- Hull, Lise (2006), Britain's medieval castles (illustrated ed.), Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 101, ISBN 978-0-275-98414-4

- Museums Staff (2011), Colchester Castle Museum: History, Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service and Colchester Borough Council, retrieved September 2011 Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Wheeler, R. E. M. (1920), "The Vaults under Colchester Castle: a further note", Journal of Roman Studies, 10: 87–89, doi:10.2307/295791

Further reading

- Crummy, Philip (1981), Aspects of Anglo-Saxon and Norman Colchester (PDF), Published by the Colchester Archaeological Trust and the Council for British Archaeology, ISBN 0-906780-06-3

- Appendix 4 Notes on Colchester Keep (PDF) This section includes a plan of the keep.

- Appendix 5 Notes on the borough seals (PDF) Borough seals include mediaeval representations of the castle.

- Wheeler, R. E. Mortimer; Laver, Philip G. (1919), "Roman Colchester", Journal of Roman Studies, 9: 139–169, doi:10.2307/296003

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Colchester Castle. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Colchester Castle Park. |

- Colchester Castle Museum

- Entry on the Gatehouse Gazetteer with a comprehensive bibliography

- English Castles - The Heritage Trail

Coordinates: 51°53′29″N 0°54′08″E / 51.89133°N 0.90217°E