Contraposition

In logic, contraposition is a law that says that a conditional statement is logically equivalent to its contrapositive. The contrapositive of the statement has its antecedent and consequent inverted and flipped: the contrapositive of is thus . For instance, the proposition "All bats are mammals" can be restated as the conditional "If something is a bat, then it is a mammal". Now, the law says that statement is identical to the contrapositive "If something is not a mammal, then it is not a bat."

The contrapositive can be compared with three other relationships between conditional statements:

- Inversion (the inverse),

- "If something is not a bat, then it is not a mammal." Unlike the contrapositive, the inverse's truth value is not at all dependent on whether or not the original proposition was true, as evidenced here. The inverse here is clearly not true.

- Conversion (the converse),

- "If something is a mammal, then it is a bat." The converse is actually the contrapositive of the inverse and so always has the same truth value as the inverse, which is not necessarily the same as that of the original proposition.

- Negation,

- "There exists a bat that is not a mammal. " If the negation is true, the original proposition (and by extension the contrapositive) is false. Here, of course, the negation is false.

Note that if is true and we are given that Q is false, , it can logically be concluded that P must be false, . This is often called the law of contrapositive, or the modus tollens rule of inference.

Intuitive explanation

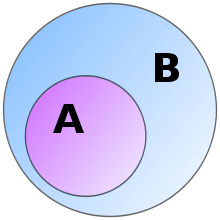

Consider the Euler diagram shown. According to this diagram, if something is in A, it must be in B as well. So we can interpret "all of A is in B" as:

It is also clear that anything that is not within B (the blue region) cannot be within A, either. This statement,

is the contrapositive. Therefore, we can say that

- .

Practically speaking, this may make life much easier when trying to prove something. For example, if we want to prove that every girl in the United States (A) has brown hair (B), we can try to directly prove by checking all girls in the United States to see if they all have brown hair. Alternatively, we can try to prove by checking all girls without brown hair to see if they are all outside the US. This means that if we find at least one girl without brown hair within the US, we will have disproved , and equivalently .

To conclude, for any statement where A implies B, then not B always implies not A. Proving or disproving either one of these statements automatically proves or disproves the other. They are fully equivalent.

Formal definition

A proposition Q is implicated by a proposition P when the following relationship holds:

This states that, "if P, then Q", or, "if Socrates is a man, then Socrates is human." In a conditional such as this, P is the antecedent, and Q is the consequent. One statement is the contrapositive of the other only when its antecedent is the negated consequent of the other, and vice versa. The contrapositive of the example is

- .

That is, "If not-Q, then not-P", or, more clearly, "If Q is not the case, then P is not the case." Using our example, this is rendered "If Socrates is not human, then Socrates is not a man." This statement is said to be contraposed to the original and is logically equivalent to it. Due to their logical equivalence, stating one effectively states the other; when one is true, the other is also true. Likewise with falsity.

Strictly speaking, a contraposition can only exist in two simple conditionals. However, a contraposition may also exist in two complex conditionals, if they are similar. Thus, , or "All Ps are Qs," is contraposed to , or "All non-Qs are non-Ps."

Simple proof by definition of a conditional

In first-order logic, the conditional is defined as:

We have:

Simple proof by contradiction

Let:

It is given that, if A is true, then B is true, and it is also given that B is not true. We can then show that A must not be true by contradiction. For, if A were true, then B would have to also be true (given). However, it is given that B is not true, so we have a contradiction. Therefore, A is not true (assuming that we are dealing with concrete statements that are either true or not true):

We can apply the same process the other way round:

We also know that B is either true or not true. If B is not true, then A is also not true. However, it is given that A is true; so, the assumption that B is not true leads to contradiction and must be false. Therefore, B must be true:

Combining the two proved statements makes them logically equivalent:

More rigorous proof of the equivalence of contrapositives

Logical equivalence between two propositions means that they are true together or false together. To prove that contrapositives are logically equivalent, we need to understand when material implication is true or false.

This is only false when P is true and Q is false. Therefore, we can reduce this proposition to the statement "False when P and not-Q" (i.e. "True when it is not the case that P and not-Q"):

The elements of a conjunction can be reversed with no effect (by commutativity):

We define as equal to "", and as equal to (from this, is equal to , which is equal to just ):

This reads "It is not the case that (R is true and S is false)", which is the definition of a material conditional. We can then make this substitution:

When we swap our definitions of R and S, we arrive at the following:

Comparisons

| name | form | description |

|---|---|---|

| implication | if P then Q | first statement implies truth of second |

| inverse | if not P then not Q | negation of both statements |

| converse | if Q then P | reversal of both statements |

| contrapositive | if not Q then not P | reversal and negation of both statements |

| negation | P and not Q | contradicts the implication |

Examples

Take the statement "All red objects have color." This can be equivalently expressed as "If an object is red, then it has color."

- The contrapositive is "If an object does not have color, then it is not red." This follows logically from our initial statement and, like it, it is evidently true.

- The inverse is "If an object is not red, then it does not have color." An object which is blue is not red, and still has color. Therefore, in this case the inverse is false.

- The converse is "If an object has color, then it is red." Objects can have other colors, of course, so, the converse of our statement is false.

- The negation is "There exists a red object that does not have color." This statement is false because the initial statement which it negates is true.

In other words, the contrapositive is logically equivalent to a given conditional statement, though not sufficient for a biconditional.

Similarly, take the statement "All quadrilaterals have four sides," or equivalently expressed "If a polygon is a quadrilateral, then it has four sides."

- The contrapositive is "If a polygon does not have four sides, then it is not a quadrilateral." This follows logically, and as a rule, contrapositives share the truth value of their conditional.

- The inverse is "If a polygon is not a quadrilateral, then it does not have four sides." In this case, unlike the last example, the inverse of the argument is true.

- The converse is "If a polygon has four sides, then it is a quadrilateral." Again, in this case, unlike the last example, the converse of the argument is true.

- The negation is "There is at least one quadrilateral that does not have four sides." This statement is clearly false.

Since the statement and the converse are both true, it is called a biconditional, and can be expressed as "A polygon is a quadrilateral if, and only if, it has four sides." (The phrase if and only if is sometimes abbreviated iff.) That is, having four sides is both necessary to be a quadrilateral, and alone sufficient to deem it a quadrilateral.

Truth

- If a statement is true, then its contrapositive is true (and vice versa).

- If a statement is false, then its contrapositive is false (and vice versa).

- If a statement's inverse is true, then its converse is true (and vice versa).

- If a statement's inverse is false, then its converse is false (and vice versa).

- If a statement's negation is false, then the statement is true (and vice versa).

- If a statement (or its contrapositive) and the inverse (or the converse) are both true or both false, it is known as a logical biconditional.

Application

Because the contrapositive of a statement always has the same truth value (truth or falsity) as the statement itself, it can be a powerful tool for proving mathematical theorems. A proof by contraposition (contrapositive) is a direct proof of the contrapositive of a statement.[1] However, indirect methods such as proof by contradiction can also be used with contraposition, as, for example, in the proof of the irrationality of the square root of 2. By the definition of a rational number, the statement can be made that "If is rational, then it can be expressed as an irreducible fraction". This statement is true because it is a restatement of a definition. The contrapositive of this statement is "If cannot be expressed as an irreducible fraction, then it is not rational". This contrapositive, like the original statement, is also true. Therefore, if it can be proven that cannot be expressed as an irreducible fraction, then it must be the case that is not a rational number. The latter can be proved by contradiction.

The previous example employed the contrapositive of a definition to prove a theorem. One can also prove a theorem by proving the contrapositive of the theorem's statement. To prove that if a positive integer N is a non-square number, its square root is irrational, we can equivalently prove its contrapositive, that if a positive integer N has a square root that is rational, then N is a square number. This can be shown by setting √N equal to the rational expression a/b with a and b being positive integers with no common prime factor, and squaring to obtain N = a2/b2 and noting that since N is a positive integer b=1 so that N = a2, a square number.