Dancer in the Dark

| Dancer in the Dark | |

|---|---|

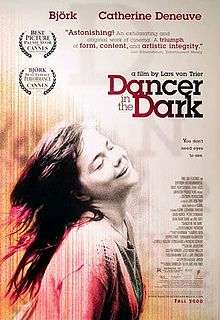

US theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Lars von Trier |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | Lars von Trier |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Björk |

| Cinematography | Robby Müller |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Fine Line Features |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 140 minutes[1][2] |

| Country | Denmark |

| Language | English |

| Budget | USD$12.5 million[3] (120 million kr) |

| Box office | $45.6 million[3][4] |

Dancer in the Dark (Danish: Danser i mørket) is a 2000 Danish musical drama film directed by Lars von Trier. It stars Icelandic singer Björk as a daydreaming immigrant factory worker who suffers from a degenerative eye condition and is saving up to pay for an operation to prevent her young son from suffering the same fate. Catherine Deneuve, David Morse, Cara Seymour, Peter Stormare, Siobhan Fallon Hogan, and Joel Grey also star.

The soundtrack for the film, released as the album Selmasongs, was written mainly by Björk, but a number of songs featured contributions from Mark Bell and the lyrics were by von Trier and Sjón. Three songs from Rodgers and Hammerstein's The Sound of Music were also used in the film.

This is the third film in von Trier's "Golden Heart Trilogy"; the other two films are Breaking the Waves (1996) and The Idiots (1998). The film was an international co-production among companies based in thirteen countries: Denmark, Argentina, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It was shot with a handheld camera, and was somewhat inspired by a Dogme 95 look.

Dancer in the Dark premiered at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival to standing ovations and controversy, but was nonetheless awarded the Palme d'Or, along with the Best Actress award for Björk. The song "I've Seen It All", with Thom Yorke, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Song but lost to "Things Have Changed" by Bob Dylan from Wonder Boys. The film continues to polarize critical opinion, being seen by some as melodramatic[5] and by others as one of the most important films of the 2000s.[6][7]

Plot

The film is set in Washington state in 1964 and focuses on Selma Ježková (Björk), a Czech immigrant who has moved to the United States with her son, Gene Ježek (Vladica Kostic). They live a life of poverty as Selma works at a factory with her good friend Kathy (Catherine Deneuve), whom she nicknames Cvalda. She rents a trailer home on the property of town policeman Bill Houston (David Morse) and his wife Linda (Cara Seymour). She is also pursued by the shy but persistent Jeff (Peter Stormare), who also works at the factory.

Selma suffers from a degenerative eye condition and because of this is losing her vision. She has been saving up to pay for an operation which will prevent her young son from suffering the same fate. To escape the misery of her daily life, Selma accompanies Kathy to the local cinema where together they watch fabulous Hollywood musicals (or more accurately, Selma listens as Cvalda describes them to her, to the annoyance of the other theater patrons, or acts out the dance steps upon Selma's hand using her fingers).

In her day-to-day life, when things are too boring or upsetting, Selma slips into daydreams or perhaps a trance-like state where she imagines the ordinary circumstances and individuals around her have erupted into elaborate musical theater numbers. These songs use some sort of real-life noise (from factory machines buzzing to the sound of a flag rapping against a flag pole in the wind) as an underlying rhythm. Unfortunately, Selma slips into one such trance while working at the factory. Soon Jeff and Cvalda begin to realize that Selma can barely see at all. Additionally, Bill reveals to Selma that his materialistic wife Linda spends more than his salary, there is no money left from his inheritance, and he is behind in payments and the bank is going to take his house. He asks Selma for a loan, but she declines. He regrets telling Selma his secret. To comfort Bill, Selma reveals her secret blindness, hoping that together they can keep each other's secret. Bill then hides in the corner of Selma's home, knowing she can't see him, and watches as she puts some money in her kitchen tin.

The next day, after having broken her machine the night before through careless error, Selma is fired from her job. When she comes home to put her final wages away she finds the tin is empty; she goes next door to report the theft to Bill and Linda only to hear Linda discussing how Bill has brought home their safe deposit box to count their savings. Linda additionally reveals that Bill has "confessed" his affair with Selma, and that Selma must move out immediately. Knowing that Bill was broke and that the money he is counting must be hers, she confronts him and attempts to take the money back. He draws a gun on her, and in a struggle he is wounded. Linda discovers the two of them and, assuming that Selma is attempting to steal the money, runs off to tell the police at Bill's command. Bill then begs Selma to take his life, telling her that this will be the only way she will ever reclaim the money that he stole from her. Selma shoots at him several times, but due to her blindness manages to only maim Bill further. In the end, she performs a coup de grâce with the safe deposit box. In one of the scenes, Selma slips into a trance and imagines that Bill's corpse stands up and slow dances with her, urging her to run to freedom. She does, and takes the money to the Institute for the Blind to pay for her son's operation before the police can take it from her.

Selma is caught and eventually put on trial. It is here that she is pegged as a Communist sympathizer and murderess. Although she tells as much truth about the situation as she can, she refuses to reveal Bill's secret, saying that she had promised not to. Additionally, when her claim that the reason she didn't have any money was because she had been sending it to her father in Czechoslovakia is proven false, she is convicted and given the death penalty. Cvalda and Jeff eventually put the pieces of the puzzle together and get back Selma's money, using it instead to pay for a trial lawyer who can free her. Selma becomes furious and refuses the lawyer, opting to face the death penalty rather than let her son go blind, but she is deeply distraught as she awaits her death. Although a sympathetic female prison guard named Brenda tries to comfort her, the other state officials show no feelings and are eager to see her executed. Brenda encourages Selma to walk. On her way to the gallows, Selma goes to hug the other men on death row while singing to them. However, on the gallows, she becomes terrified, so that she must be strapped to a collapse board. Her hysteria when the hood is placed over her face delays the execution. Selma begins crying hysterically and Brenda cries with her, but Cvalda rushes to inform her that the operation was successful and that Gene will see. Relieved, Selma sings the final song on the gallows with no musical accompaniment, although she is hanged before she finishes. A curtain is then drawn in front of her body, while the missing part of the song shows on the screen: "They say it's the last song/They don't know us, you see/It's only the last song/If we let it be."

Cast

- Björk as Selma Ježková

- Catherine Deneuve as Kathy (Cvalda)

- David Morse as Bill Houston

- Peter Stormare as Jeff

- Jean-Marc Barr as Norman

- Joel Grey as Oldřich Nový

- Cara Seymour as Linda Houston

- Siobhan Fallon as Brenda

- Vladica Kostic as Gene Ježek

- Vincent Paterson as Samuel

- Željko Ivanek as District attorney

- Udo Kier as Dr. Pokorný

- Jens Albinus as Morty

- Reathel Bean as Judge

- Michael Flessas as Angry man

- Mette Berggreen as Receptionist

- Lars Michael Dinesen as Defense attorney

- Katrine Falkenberg as Suzan

- Stellan Skarsgård as the doctor

Style

Much of the film has a similar look to von Trier's earlier Dogme 95-influenced films: it is filmed on low-end, hand-held digital cameras to create a documentary-style appearance. It is not a true Dogme 95 film, however, because the Dogme rules stipulate that violence, non-diegetic music, and period pieces are not permitted. Trier differentiates the musical sequences from the rest of the film by using static cameras and by brightening the colours.

Production

The film's title suggests the Fred Astaire/Cyd Charisse duet "Dancing in the Dark" from the 1953 film The Band Wagon, which ties in with the film's musical theatre theme.

Actress Björk, who is known primarily as a contemporary composer, had rarely acted before, and has described the process of making this film as so emotionally taxing that she would not appear in any film ever again[8][9] (although in 2005, she appeared in Matthew Barney's Drawing Restraint 9). She had disagreements with the director over the content of the film, wanting the ending to be more uplifting. She later called von Trier sexist.[10] Deneuve and others have described her performance as feeling rather than acting.[11] Björk has said that it is a misunderstanding that she was put off acting by this film; rather, she never wanted to act but made an exception for Lars von Trier.[12]

The musical sequences were filmed simultaneously with over 100 digital cameras so that multiple angles of the performance could be captured and cut together later, thus shortening the filming schedule.

Björk lies down on a stack of birch logs during the "Scatterheart" sequence. In Icelandic, Faroese, and Swedish, "Björk" means "birch."

A Danish MY class locomotive (owned by Swedish train operator TÅGAB) was painted in the American Great Northern scheme for the movie, and not repainted afterward.[13] A T43 class locomotive was repainted too, though never used in the film.

Critical response

Reaction to Dancer in the Dark was polarized. For example, on The Movie Show, Margaret Pomeranz gave it five stars while David Stratton gave it a zero, a score shared only by Geoffrey Wright's Romper Stomper (1992).[14][15] Stratton later described it as his "favourite horror film".[16] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian said it was "one of the worst films, one of the worst artworks and perhaps one of the worst things in the history of the world."[17] The response is reflected in the film's official website, which posts both positive and negative reviews on its main page.[18] The diverse reviews result in an overall "Fresh" rating; 68% grade on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes.[19]

The film was praised for its stylistic innovations. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times stated: "It smashes down the walls of habit that surround so many movies. It returns to the wellsprings. It is a bold, reckless gesture."[20] Edward Guthmann from the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, "It's great to see a movie so courageous and affecting, so committed to its own differentness."[21]

However, criticism was directed at its storyline. Jonathan Foreman of the New York Post described the film as "meretricious fakery" and called it "so unrelenting in its manipulative sentimentality that, if it had been made by an American and shot in a more conventional manner, it would be seen as a bad joke."[22]

Awards

Dancer in the Dark premiered at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival and was awarded the Palme d'Or, along with the Best Actress award for Björk.[23] The song "I've Seen It All" was nominated for an Oscar for best song, at the performance of which Björk wore her famous swan dress.

Sight & Sound magazine conducts a poll every ten years of the world's finest film directors to find out the Ten Greatest Films of All Time. This poll has been going since 1952, and has become the most recognised[24] poll of its kind in the world. In 2012[25] Cyrus Frisch voted for "Dancer in the Dark". Frisch commented: "A superbly imaginative film that leaves conformity in shambles."

- Won

- Award of the Japanese Academy - Best Foreign Film

- Bodil Award - Best Actress (Björk)

- Cannes Film Festival - Best Actress (Björk)[23]

- Cannes Film Festival - Golden Palm Award (Lars von Trier)[23]

- Edda Awards (Iceland) - Best Actress (Björk)

- European Film Awards - Best Actress (Björk)

- European Film Awards - Best Film

- Golden Satellite Awards - Best Original Song (I've Seen It All)

- Goya Awards - Best European Film (Lars von Trier)

- Independent Spirit Awards - Best Foreign Film (Lars von Trier)

- Nominated

- Academy Award - Best Original Song (I've Seen It All)

- Bodil Award - Best Film

- BRIT Awards - Best Soundtrack

- Camerimage Awards - Gold Frog Award

- Chicago Film Critics Association Awards - Best Actress (Björk)

- Chicago Film Critics Association Awards - Best Original Score

- Cinema Writers Circle Awards (Spain) - Best Foreign Film

- César Awards (France) - Best Foreign Film

- Golden Globe Awards - Best Actress in a Film - Drama (Björk)

- Golden Globe Awards - Best Original Song (I've Seen It All)

- Golden Satellite Awards - Best Drama

- Golden Satellite Awards - Best Actress, Drama (Björk)

- Golden Satellite Awards - Best Supporting Actress, Drama (Catherine Deneuve)

Music

- Original music: Björk

- Singers: Björk, Catherine Deneuve, Siobhan Fallon, David Morse, Cara Seymour, Edward Ross (for Vladica Kostic), Joel Grey, Peter Stormare (In the soundtrack Selmasongs, Thom Yorke sings instead of Stormare)

- Lyrics: Björk, Lars von Trier and Sjón

- Non-original music: Richard Rodgers (from 'The Sound of Music')

- Non-original lyrics: Oscar Hammerstein II (from 'The Sound of Music')

- Choreographer: Vincent Paterson

References in other media

- Finnish band The Rasmus included a song called "Dancer in the Dark" in the special edition of their 2005 album Hide from the Sun. The song is about the film.

- Drummer Jeff "Tain" Watts arranged and recorded a version of "107 Steps" on his live album Detained: Live at the Blue Note.

- The character of Selma's father, Oldřich Nový, was an actual movie and musical star in Czechoslovakia.

- The independent spoof film My Big Fat Independent Movie features a musical number in the style of Dancer in the Dark, with the main female character wearing a version of Björk's swan dress.

References

- ↑ Lasagna, Roberto; Lena, Sandra (May 2003). Lars von Trier. Gremese Editore. p. 124. ISBN 978-88-7301-543-7. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ↑ "DANCER IN THE DARK (15)". British Board of Film Classification. July 13, 2000. Retrieved January 2, 2013.

- 1 2 "Dancer in the Dark - Box Office Data". The Numbers. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ "Dancer in the Dark (2000)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ Bradshaw, Peter (September 14, 2000). "Dancer in the dark". The Guardian. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Oliver Schmitz". British Film Institute. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ↑ "TSPDT - 21st Century (Full List)". March 8, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Bjork launches celluloid comeback". BBC News. 2005-11-02. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

Bjork vowed never to act again after making Dancer in the Dark in 2000, despite winning a best actress prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

- ↑ "Björk Uncovers Dancer Feud". TVGuide.com. October 2000. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

Right now, I feel very strong about focusing on music

- ↑ Bryan Appleyard (2009-07-12). "Should Lars von Trier's Antichrist be banned?". London: The Times. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ↑ Pytlik, Mark (29 May 2003). Bjork: Wow and Flutter. ECW Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-55022-556-3. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ↑ http://www.bjork.com/facts/about/right.php?id=1574

- ↑ RailPictures.Net Photo » TAGAB TMY

- ↑ Pomeranz, Margeret (September 2012). "Dancer In The Dark".

- ↑ "At the Movies' Margaret Pomeranz and David Stratton's best bust-ups". News.com.au. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Summer Broadband Specials - Musicals". ABC At the Movies. ABC. 9 December 2004. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ Bradshaw, Peter (2009-05-22). "Dancer In The Dark". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-05-22.

Xan Brooks leads a critics' roundtable on the highs and lows, the sublime to the ridiculous at the 2009 Cannes film festival, before sailing into the sunset. See video at 8:20.

- ↑ "Dancer in the Dark official website". Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ↑ "Dancer In The Dark". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (2000-10-20). "Dancer In The Dark". Chicago Sun Times. rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

Some reasonable people will admire Lars von Trier's "Dancer in the Dark," and others will despise it. An excellent case can be made for both positions.

- ↑ Guthmann, Edward (2000-10-26). "`Dancer' Dares to Be Different". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

Singer Bjork amazing in von Trier's tragedy

- ↑ Foreman, Jonathan (2000-09-22). "Dreck Dressed As Art". New York Post. NYP Holdings, Inc. p. 47. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

Despite 2 Good Performances, 'Dancer' Is Just Fakery With An Anti-american Drum To Beat

- 1 2 3 "Festival de Cannes: Dancer in the Dark". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ http://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/the-best-damned-film-list-of-them-all

- ↑ http://explore.bfi.org.uk/sightandsoundpolls/2012/voter/920

- Georg Tiefenbach: Drama und Regie (Writing and Directing): Lars von Trier's Breaking the Waves, Dancer in the Dark, Dogville. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2010. ISBN 978-3-8260-4096-2.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dancer in the Dark |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dancer in the Dark. |

- Dancer in the Dark at the Internet Movie Database

- Dancer in the Dark at Box Office Mojo

- Dancer in the Dark at Rotten Tomatoes

- Dancer in the Dark at Metacritic

- Review by Sian Kirwan - BBC

- Review at The Film Experience

- Review by A. O. Scott - The New York Times

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by All About My Mother |

European Film Award for Best European Film 2000 |

Succeeded by Amélie |