Dixie Dean

| |||

| Personal information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | William Ralph Dean | ||

| Date of birth | 22 January 1907[1] | ||

| Place of birth | Birkenhead, Cheshire, England | ||

| Date of death | 1 March 1980 (aged 73) | ||

| Place of death | Goodison Park, Liverpool, England | ||

| Height | 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m) | ||

| Playing position | Centre forward | ||

| Senior career* | |||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) |

| 1923–1925 | Tranmere Rovers | 30 | (27) |

| 1925–1937 | Everton | 399 | (349) |

| 1938–1939 | Notts County | 9 | (3) |

| 1939 | Sligo Rovers | 7 | (10) |

| 1940 | Hurst | 2 | (1) |

| Total | 447 | (390) | |

| National team | |||

| 1927–1932 | England | 16 | (18) |

|

* Senior club appearances and goals counted for the domestic league only. | |||

William Ralph "Dixie" Dean (22 January 1907 – 1 March 1980) was an English footballer who played as a centre forward.

Born in Birkenhead, he began his career at his hometown club Tranmere Rovers before moving on to Everton, the club he had supported as a child. He was particularly known for scoring goals with his head. Dean played the majority of his career at Everton before injuries caught up with him and he moved on to new challenges at Notts County. He is best known for his exploits during the 1927–28 season, which saw him score a record 60 league goals. He also scored 18 goals in 16 appearances for England.

A statue of Dean was unveiled outside Goodison Park in May 2001. A year later, he became one of 22 players inducted into the inaugural English Football Hall of Fame. Dean was the first Everton player to wear the number-9 shirt, which in later years would become iconic at the club.

Early years

Dean was born at 313 Laird Street in Birkenhead, Cheshire, across the River Mersey from Liverpool. Dean's family on both sides hailed from Chester. He was the grandson of Ralph Brett, a train driver who drove the royal train during the reign of George V. Dean grew up as a supporter of Everton thanks to the efforts of his father, William Sr., who took him to a match during the 1914–1915 title-winning season.

Dean's childhood coincided with the First World War, and between the ages of 7 and 11 he delivered cow's milk to local families as part of the "war effort: "Well, it was war time you see, so you were grafting all the time. I used to take milk out. I'd be up at half-past four in the morning and go down and get the ponies and the milk floats, then I'd come out to this place in Upton, between Upton and Arrowe Park, and Burgess' Farm was there. We used to collect the milk in the big urns and take it out to people's houses, serving it out of the ladle. And not only that, you had an allotment, and that was in school time. And there was no such thing as pinching and stealing and all that bloody caper. In those days, you were growing all that stuff and you needed it for the war time."[2]

Dean attended Laird Street School,[3] but felt he received no formal education: "My only lesson was football ... I used to give the pens out on Friday afternoons ... the ink, and the chalks. That was the only job I had in school ... I never had any lessons."[2] When he turned 11 he attended Albert (Memorial) Industrial School, a borstal school in Birkenhead, because of the football facilities on offer. The Dean family home had little room for him due to the family's size; Dean was happy with the arrangement, since he could play on the school's football team.[3] Dean falsely told fellow pupils he had been caught stealing, since he wanted to be "one of the boys".

He left school at 14 and worked for Wirral Railway as an apprentice fitter; his father also worked there, and had been working since he was 11 years old[2] for Great Western Railway. The elder Dean later became a train driver before moving to Birkenhead to work for Wirral Railway, to be closer to his future wife (and William Jr.'s mother) Sarah. Dean's father would later retire with the company.[3]

Dean took a night job so that he could concentrate on his first love, football: "The other two apprentice fitters, they didn't like the night job because there were too many bloody rats around there, coming out of the Anglo-Oil company and the Vacuum Oil Company ... rats as big as whippets. So I took their night job, and of course, I could always have a game of football then."[2] Dean would kick the trespassing rats against the wall.

The sons of Dean's manager at Wirral Railway were directors of New Brighton A.F.C., and they were interested in signing Dean. However, Dean told the club he was not interested in signing and instead played for local team Pensby United in Pensby. It was at Pensby United where Dean attracted the attention of a Tranmere Rovers scout.[2]

"Dixie" nickname

Some said that Dean and his family disliked his nickname, and preferred people to call him "Bill" or "Billy". The popular theory regarding how Dean acquired his nickname is that he did so in his youth, perhaps due to his dark complexion and hair (which bore a resemblance to people from the Southern United States).[4] In Dean's obituary in The Times, Geoffrey Green suggested that the nickname was taken from a "Dixie" song that was popular during Dean's childhood; there was "something of the Uncle Tom about his features".[5]

Alternatively, Tranmere Rovers club historian Gilbert Upton uncovered evidence, verified by Dean's late Godmother, that the name "Dixie" was a corruption of his childhood nickname, Digsy (acquired from his approach to the children's game of tag, where Dean would dig his fist into a girl's back— hence "Digsy").[6]

Club career

Tranmere Rovers

He played football for Laird Street School, Moreton Bible Class, Heswell and Pensby United. He then joined the pro ranks with his local club, Tranmere Rovers in November 1923. He was 16 at the time.

Whilst at Tranmere, he was on the receiving end of a tough challenge which resulted in him losing a testicle in a reserve game against Altrincham.[7][8] Immediately following the challenge, a teammate rubbed the area to ease the pain. Dean shouted "Don't rub 'em, count 'em!".

In his 16 months at Tranmere spanning seasons 1923/24 and 1924/25 he scored 27 goals in 30 league appearances. All 27 were in the second of those two seasons in which he averaged exactly a goal per game. His exploits attracted the interest of many clubs across England, including Arsenal and Newcastle United.[2] Upon leaving Tranmere Rovers, secretary Bert Cooke reneged on an agreement to pay 10 percent of the transfer fee to Dean. Dean was paid one percent of the fee, which he gave to his parents (who donated it to Birkenhead General Hospital).

Everton

His father had taken him to a league game at Goodison Park when he was eight years old. It was a dream come true for Dean when Everton secretary Thomas H. McIntosh arranged to meet him at the Woodside Hotel in 1925. Dean was so excited that he ran the 2.5 miles (4.0 km) distance from his home in north Birkenhead to the riverside to meet him.[2] He signed for Everton in March 1925 having just turned 18.

He later revealed that he expected a £300 signing fee to be given to his parents when he transferred to Everton. They received only £30, and Tranmere Rovers manager Bert Cooke told him "that's all the League will allow". Dean appealed to John McKenna, chairman of the Football Association, but was told "I'm afraid you've signed, and that's it."[2] Dean signed for Everton for £3,000, then a record fee received for Tranmere Rovers. He made an immediate impact, scoring 32 goals in his first full season. A motorcycling accident at Holywell, North Wales in summer 1926 left Dean with a fractured skull and jaw, and doctors were unsure whether he would be able to play again. In his next game for Everton he scored using his head, leading Evertonians to joke that the doctor left a metal plate in Dean's head.

Dean's greatest point of note is he is still the only player in English football score 60 league goals in one season (1927–28).[9] At that season's end he was 21 years old. Middlesbrough's George Camsell, who holds the highest goals-to-games ratio for England, had scored 59 league goals the previous season.

In that 1927-28 season Everton won the First Division title. When they were relegated to Second Division in 1930 Dean stayed with them. The club went on to immediately win the Second Division in 1931 followed by the First Division again in 1932. They then immediately won the FA Cup in 1933 (in which he scored in the final) – a sequence unmatched since.

In December 1933, Dean issued a public appeal to have stolen goods returned to him. The Times issued a statement: "Dixie Dean, the Everton and England forward appeals to the thief who robbed him of an international cap and presentation clock to return them. His house in Caldy Road, Walton, Liverpool was entered in his absence over Christmas, and the thief left behind gold watches and jewelry (sic)." [10] By then, Dean was captain of the side. However, the harsh physical demands of the game (as it was played then) took their toll and he was dropped from the first team in 1937.

Notts County

Dean went on to play for Notts County for one season, in which he scored three goals in nine games.

Sligo Rovers

At age 32, Dean signed for Irish team Sligo Rovers in January 1939 to help the club in their FAI Cup campaign. On his arrival, the Railway station in Sligo was said to be filled with locals trying to catch a glimpse of him. Dean scored ten goals in seven games for the club,[11] including five in a 7–1 win over Waterford (which remains a club record for the most goals scored in a single game). He also played in four Cup matches, scoring once (in the 1–1 final against Shelbourne, who won the replay 1–0). Dean's runner-up medal was later stolen from his hotel room; on a return trip to Ireland to watch Rovers 39 years later in the 1978 FAI Cup final, a package was delivered to his hotel room with the medal inside.

Hurst

Dean ended his professional playing days with Hurst (now Ashton United) in the Cheshire County League 1939–40 season, managing two games (and one goal) before the outbreak of war truncated his career. He made his debut is a 4–0 loss to Stalybridge Celtic; 5,600 people attended the game, earning the club gate receipts of £140.[12]

International career

Dean made his début for the England national football team against British rivals Wales at the Racecourse Ground in Wrexham in February 1927, less than a month after his 20th birthday. His final game for England came in a 1–0 victory over Ireland in October 1932 at Blackpool F.C.'s Bloomfield Road, when Dean was 25 years old.

Dean was involved in the 1927 and 1929 editions of the British Home Championship. During the 1927 edition, Dean scored four goals in his two games for England and scored twice against Scotland at Hampden Park. Despite the loss, the Scots won the competition overall and applauded Dean (who finished the tournament as top scorer). In the 1929 edition, he scored in his only outing against Ireland at Goodison Park.

The only international competitions outside the British Home Championship during Dean's international career were the 1928 and 1936 Olympic Games and the inaugural FIFA World Cup, which took place in 1930; however, neither Great Britain nor England participated. Dean represented England 16 times, scoring 18 goals in 8 games (including hat-tricks against Belgium and Luxembourg).

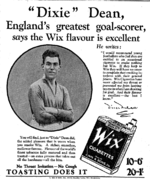

Endorsements

Dean was involved in many product endorsements.

Personal life and post-football career

Dean became a Freemason in 1931 while playing for Everton and England. He was initiated in Randle Holme Lodge, No. 3261 on 18 February 1931 in Birkenhead, Wirral.[13]

After retiring, he went on to run the Dublin Packet pub in Chester (Everton and the Dublin Packet commemorate this with memorabilia) and work at Littlewoods football pools as a porter at their Walton Hall Avenue offices (where he was remembered by fellow workers as a quiet, unassuming man).

Declining health and death

In January 1972, Dean was admitted to St. Catherine's hospital in Birkenhead suffering from the effects of influenza[14] and was released a month later.[15] In November 1976, he had his right leg amputated due to a blood clot; Dean's health was declining, and he became increasingly homebound.

Dean died on 1 March 1980 at age 73 after suffering a heart attack at Everton's home ground Goodison Park whilst watching a match against their closest rivals, Liverpool. It was the first time that Dean had visited Goodison Park in several years, due to ill health. "He belongs to the company of the supremely great, like Beethoven, Shakespeare and Rembrandt", said Bill Shankly.[16] His funeral took place at St. James' Church on Laird Street (the street where he was born) in Birkenhead.[17] Dean was survived by his four children: William, Geoffrey, Ralph and Barbara; he outlived his wife Ethel, who died of a heart attack in 1974 after 43 years of marriage.[18]

Legacy

Dean was an internationally known figure. Military records show that during the Second World War, an Italian prisoner of war was captured by British troops in the Western Desert and told his captors "f**k your Winston Churchill and f**k your Dixie Dean".[19] One of the soldiers present was Liverpool-born Patrick Connelly, who later went into show business using the pseudonym "Bill Dean".[19]

Everton arranged a testimonial for Dean on 7 April 1964. Over 34,000 people saw teams from Scotland and England (composed of players from Everton and Liverpool) compete;[20] The "Scots" (with one Englishman and one Welshman) won, 3–1.[21]

The match raised £7,000 for Dean.

| England | Scotland |

|---|---|

Dean's 1933 FA Cup winners medal sold for £18,213 at auction in March 2001.[22] In May 2001 local sculptor Tom Murphy created a statue of Dean, which was erected outside the park end of Goodison Park at a cost of £75,000 with the inscription "Footballer, Gentleman, Evertonian".[23] In 2002, Dean was an inaugural inductee to the English Football Hall of Fame.[24] There is an annual Dixie Dean award, which is given to the Merseyside player of the year; it has been won by players from his former clubs (Tranmere and Everton) and Liverpool F.C.[25]

When asked if he thought his record of scoring 60 goals in a season would be broken, Dean said: "People ask me if that 60-goal record will ever be beaten. I think it will. But there's only one man who'll do it. That's the fellow that walks on the water. I think he's about the only one." In total, Dean scored 383 goals for Everton in 433 appearances—an exceptional strike-rate which includes 37 hat-tricks. He was known as a sporting player, never booked or sent off during his career despite rough treatment and provocation from opponents.[26] Only Arthur Rowley has scored more English-league career goals; however, while Rowley made 619 appearances and scored 433 goals (0.70 goals per game) Dean scored 379 goals in 438 games (0.87 goals per game).

Achievements

Everton

- League Championship: 2 (1928, 1932)

- Second Division Championship: 1 (1931)

- FA Charity Shield: 2 (1928, 1932)

- FA Cup: 1 (1933)

- Central League Championship: 1 (1938)

Sligo Rovers

- League of Ireland Runners Up: 1 (1939)

- FAI Cup Runners Up: 1 (1939)

Individual

- England Caps: 16

- England Goals: 18

- Football League Representative appearances: 6

- Football League Representative goals: 9

- Sunday Pictorial Trophy for 60 league goals in 1927–28

- Lewis's Medal to commemorate 200 league goals in 199 appearances

- Hall of Fame Trophy (1971)

- Football Writers' Association inscribed silver salver (1976)

- Inaugural inductee in the National Football Museum Hall of Fame (2002)

- Most goals in an English top-flight season: 60

Career statistics

| Club | Division | Season | League | FA Cup | Club Total | International | Total Games | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | |||||

| Notts County | Third | 1938–39 | 6 | 3 | - | - | 6 | 3 | - | - | 6 | 3 | ||

| Third | 1937–38 | 3 | 0 | - | - | 3 | 0 | - | - | 3 | 0 | |||

| Total | 9 | 3 | - | - | 9 | 3 | - | - | 9 | 3 | ||||

| Everton | First | 1937–38 | 5 | 1 | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | 5 | 1 | ||

| First | 1936–37 | 36 | 24 | 4 | 3 | 40 | 27 | - | - | 40 | 27 | |||

| First | 1935–36 | 29 | 17 | - | - | 29 | 17 | - | - | 29 | 17 | |||

| First | 1934–35 | 38 | 26 | 5 | 1 | 43 | 27 | - | - | 43 | 27 | |||

| First | 1933–34 | 12 | 9 | - | - | 12 | 9 | - | - | 12 | 9 | |||

| First | 1932–33 | 39 | 24 | 6 | 5 | 45 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 46 | 29 | |||

| First | 1931–32 | 38 | 45 | 1 | 1 | 39 | 46 | 1 | 1 | 40 | 47 | |||

| Second | 1930–31 | 37 | 39 | 5 | 9 | 42 | 48 | 1 | 0 | 43 | 48 | |||

| First | 1929–30 | 25 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 27 | 25 | - | - | 27 | 25 | |||

| First | 1928–29 | 29 | 26 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 26 | 3 | 1 | 33 | 27 | |||

| First | 1927–28 | 39 | 60 | 2 | 3 | 41 | 63 | 5 | 4 | 46 | 67 | |||

| First | 1926–27 | 27 | 21 | 4 | 3 | 31 | 24 | 5 | 12 | 36 | 36 | |||

| First | 1925–26 | 38 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 40 | 33 | - | - | 40 | 33 | |||

| First | 1924–25 | 7 | 2 | - | - | 7 | 2 | - | - | 7 | 2 | |||

| Total | 399 | 349 | 32 | 28 | 431 | 377 | 16 | 18 | 447 | 395 | ||||

| Tranmere Rovers | Third | 1924–25 | 27 | 27 | 3 | 0 | 30 | 27 | - | - | 30 | 27 | ||

| Third | 1923–24 | 3 | 0 | - | - | 3 | 0 | - | - | 3 | 0 | |||

| Total | 30 | 27 | 3 | 0 | 33 | 27 | - | - | 33 | 27 | ||||

| Career Totals | 438 | 379 | 35 | 28 | 473 | 407 | 16 | 18 | 489 | 425 | ||||

International goals

| Goal Number | Date Scored | Stadium | Final score | Opponent | Minute goal scored | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 February 1927 | Racecourse Ground | 3–3 | [27] | ||

| 2 | 12 February 1927 | Racecourse Ground | 3–3 | [27] | ||

| 3 | 2 April 1927 | Hampden Park | 2–1 | [28] | ||

| 4 | 2 April 1927 | Hampden Park | 2–1 | [28] | ||

| 5 | 11 May 1927 | Molenbeek | 9–1 | [29] | ||

| 6 | 11 May 1927 | Molenbeek | 9–1 | [29] | ||

| 7 | 11 May 1927 | Molenbeek | 9–1 | [29] | ||

| 8 | 21 May 1927 | Stade de la Frontière | 5–2 | [30] | ||

| 9 | 21 May 1927 | Stade de la Frontière | 5–2 | [30] | ||

| 10 | 21 May 1927 | Stade de la Frontière | 5–2 | [30] | ||

| 11 | 26 May 1927 | Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir | 6–0 | [31] | ||

| 12 | 26 May 1927 | Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir | 6–0 | [31] | ||

| 13 | 17 May 1928 | Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir | 5–1 | [32] | ||

| 14 | 17 May 1928 | Stade Olympique Yves-du-Manoir | 5–1 | [32] | ||

| 15 | 19 May 1928 | Olympisch Stadion | 3–1 | [33] | ||

| 16 | 19 May 1928 | Olympisch Stadion | 3–1 | [33] | ||

| 17 | 22 October 1928 | Goodison Park | 2–1 | [34] | ||

| 18 | 9 December 1931 | Arsenal Stadium | 7–1 | [35] |

References

Citations

- ↑ "Dixie Dean". The FA. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Roberts, John. "Interview with John Roberts". SportingIntelligence.com. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 Keith 2003, p. 10.

- ↑ Prentice, David (23 January 2007). "Footballing world wakes up to Dixie". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ↑ Green, Geoffrey. "Mr Dixie Dean". The Times. p. 16.

- ↑ Upton 1992.

- ↑ Keith 2003, p. 8.

- ↑ "The seven deadly sins of football: Wrath – From Big Jack Charlton to the fan's hand grenade at Millwall". The Guardian. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ "English League Leading Goalscorers 1889–2007". RSSSF. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ↑ "News in brief". The Times. 30 December 1933. p. 7.

- ↑ Randles, Dave (9 December 2009). "The cameo that shaped Seamus". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ "Dixie Dean". Ashton United. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ Article "The Beautiful Game" by Patrick Kidd and Matthew Scanlan, published in "Freemasonry Today," No.11, Summer 2010

- ↑ "News in brief". The Times. 20 January 1972. p. 2.

- ↑ "News in brief". The Times. 21 February 1972. p. 4.

- ↑ "Hall of fame inductee: Dixie Dean". nationalfootballmuseum.com. 2002. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ "News in brief". The Times. 8 March 1980. p. 3.

- ↑

- 1 2 Keith 2003, p. 6.

- ↑ "Dixie Dean Testimonial Programme". evertoncollection.org.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ↑ "Join tribute to "Dixie" Dean". The Times. 8 April 1964. p. 5.

- ↑ "14ct gold medal". Christies Auction House. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ↑ "Tom Murphy: Dixie Dean". Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ "Everton FC 12 days of Christmas – 12 Hall of Fame legends". Liverpool Daily Post. 24 December 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ↑ "Football's finest traditions upheld with Liverpool Echo's Dixie Dean Memorial Award". Liverpool Echo. 17 February 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ Winner 2005.

- 1 2 "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- 1 2 "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- 1 2 "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- 1 2 "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- 1 2 "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ "EnglandFC Match Data". England FC. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

Sources

- Keith, John (2003). Dixie Dean: The Inside Story of a Football Icon. Robson Books. ISBN 978-1-86105-632-0.

- Upton, Gilbert (1992). Dixie Dean of Tranmere Rovers 1923–1925. Gilbert Upton. ISBN 978-0-9518648-1-4.

- Winner, David (2005). Those Feet: A Sensual History of English Football. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-7914-4.

- Walsh, Nick (1978). Dixie Dean: The Official Biography of a Goalscoring Legend. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-25619-3.

- Young, Percy M. (1963). Football on Merseyside. London.

External links

- Biography on Everton website

- A fan's personal tribute

- Association of Football Statisticians article

- English Football Hall of Fame Profile

- Dixie Dean at the Internet Movie Database