Donald Crowhurst

Donald Charles Alfred Crowhurst (1932–1969) was a British businessman and amateur sailor who died while competing in the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, a single-handed, round-the-world yacht race. Crowhurst had entered the race in hopes of winning a cash prize from The Sunday Times to aid his failing business. Instead, he encountered difficulty early in the voyage, and secretly abandoned the race while reporting false positions, in an attempt to appear to complete a circumnavigation without actually circling the world. Evidence found after his disappearance indicates that this attempt ended in insanity and suicide.

Early life

Crowhurst was born in 1932 in Ghaziabad, British India. His mother was a school teacher and his father worked on the Indian railways. During her pregnancy, his mother had longed for a daughter, and Crowhurst was raised as a girl until the age of seven.[1] After India gained its independence, his family moved back to England. The family's retirement savings were invested in an Indian sporting goods factory, which later burned down during rioting after the Partition of India.[2]

Crowhurst's father died in 1948. Due to family financial problems, he was forced to leave school early and started a five-year apprenticeship at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough Airfield. In 1953 he received a Royal Air Force commission as a pilot,[3] but was asked to leave the Royal Air Force in 1954 for reasons that remain unclear,[4] and was subsequently commissioned in to the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers in 1956.[5][6] After leaving the Army in the same year owing to a disciplinary incident,[7] Crowhurst eventually moved to Bridgwater, where he started a business called Electron Utilisation. He was active in his local community as a member of the Liberal Party and was elected to Bridgwater Borough Council.[8]

Business ventures

Crowhurst, a weekend sailor, designed and built a radio direction finder called the Navicator, a handheld device that allowed the user to take bearings on marine and aviation radio beacons.[9] While he did have some success selling his navigational equipment, his business began to fail. In an effort to gain publicity, he started trying to gain sponsors to enter the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race. His main sponsor was English entrepreneur Stanley Best, who had invested heavily in Crowhurst's failing business. Once committed to the race, Crowhurst mortgaged both his business and home against Best's continued financial support, placing himself in a grave financial situation.

The Golden Globe

The Golden Globe Race was inspired by Francis Chichester's successful single-handed round-the-world voyage, stopping in Sydney. The considerable publicity his achievement garnered led a number of sailors to plan the next logical step – a non-stop, single-handed, round-the-world sail.

The Sunday Times had sponsored Chichester, with highly profitable results, and was interested in being involved with the first non-stop circumnavigation; but they had the problem of not knowing which sailor to sponsor. They solved this by declaring the Golden Globe Race, a single-handed round-the-world race, open to all comers, with automatic entry. This was in contrast to other races of the time, for which entrants were required to demonstrate their single-handed sailing ability prior to entry.[10] Entrants were required to start between 1 June and 31 October 1968, in order to pass through the Southern Ocean in summer.[11] The prizes offered were the Golden Globe trophy for the first single-handed circumnavigation, and a £5,000 cash prize for the fastest. This was a considerable sum then, equivalent to £60,600 in 2016.[12]

The other contestants were Robin Knox-Johnston, Nigel Tetley, Bernard Moitessier, Chay Blyth, John Ridgway, William King, Alex Carozzo and Loïck Fougeron. "Tahiti" Bill Howell, a noted multihull sailor and competitor in the 1964 and 1968 OSTAR races, originally signed up as an entrant but did not actually race.

Crowhurst hired Rodney Hallworth, a crime reporter for the Daily Mail and then the Daily Express, as his public relations officer.[13]

Crowhurst's boat and preparations

The boat Crowhurst built for the trip, Teignmouth Electron, was a 40-foot (12 m) trimaran designed by Californian Arthur Piver. At the time, this was an unproven type of sailing boat for a voyage of such length. Trimarans have the potential to sail much more quickly than monohulled sailboats, but early designs in particular could be very slow if overloaded, and had considerable difficulty sailing close to the wind. Trimarans are popular with many sailors for their stability; however, if capsized (for example by a rogue wave), they are virtually impossible to right, in contrast to monohulls, and without external assistance this would typically be a fatal disaster for the boat's crew.

To improve the safety of the boat, Crowhurst had planned to add an inflatable buoyancy bag on the top of the mast to prevent capsizing; the bag would be activated by water sensors on the hull designed to detect an impending capsize. This innovation would hold the boat horizontal, and a clever arrangement of pumps would allow him to flood the uppermost outer hull, which would (in conjunction with wave action) pull the boat upright. His scheme was to prove these devices by sailing round the world with them, then go into business manufacturing the system.

However, Crowhurst had a very short time in which to build and equip his boat while securing financing and sponsors for the race. In the end, all of his safety devices were left uncompleted; he planned to complete them while underway. Also, many of his spares and supplies were left behind in the confusion of the final preparations. On top of it all, Crowhurst had never sailed on a trimaran before taking delivery of his boat several weeks before the beginning of the race.

On Sunday 13 October experienced sailor Lieutenant Commander Peter Eden volunteered to accompany Crowhurst on his last leg from Cowes to Teignmouth. Crowhurst had fallen into the water several times while in Cowes, and as he and Eden climbed aboard Teignmouth Electron, he once again ended up in the water after slipping on the outboard bracket on the stern of the rubber dinghy. Eden's description of his two days with Crowhurst provides the most expert independent assessment available for both boat and sailor before the start of the race. He recalls that the trimaran sailed immensely swiftly, but could get no closer to the wind than 60 degrees. The speed often reached 12 knots, but the vibrations encountered caused the screws on the Hasler self-steering gear to come loose. Eden said, "We had to keep leaning over the counter to do up the screws. It was a tricky and time consuming business. I told Crowhurst he should get the fixings welded if he wanted it to survive a longer trip!" Eden also commented that the Hasler worked superbly and the boat was "certainly nippy."

Eden reported that Crowhurst's sailing techniques were good, "But I felt his navigation was a mite slapdash. I prefer, even in the Channel, to know exactly where I am. He didn't take too much bother with it, merely jotting down figures on few sheets of paper from time to time." After struggling against westerlies and having to tack out into the Channel twice they arrived at 2.30 pm on 15 October, where an enthusiastic BBC film crew started filming Eden in the belief he was Crowhurst. There were 16 days to get ready before the race's deadline on October 31.[14]

Departure and deception

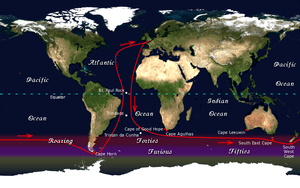

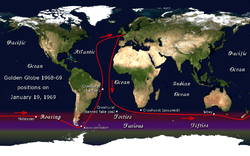

Crowhurst left from Teignmouth, Devon, on the last day permitted by the rules: 31 October 1968. He encountered immediate problems with his boat, his equipment, and his lack of open-ocean sailing skills and experience. In the first few weeks he was making less than half of his planned speed. He did not have the skill to sail the complex tri-hulled boat at anything near its optimum speed while navigating a good course. According to his logs, he gave himself only 50/50 odds of surviving the trip, assuming that he was able to complete some of the boat's safety features before reaching the dangerous Southern Ocean. Crowhurst was thus faced with the choice of either quitting the race and facing financial ruin and humiliation or continuing to an almost certain death in his unseaworthy, disappointing boat. Over the course of November and December 1968, the hopelessness of his situation pushed him into an elaborate deception. He shut down his radio with a plan to loiter in the South Atlantic for several months while the other boats sailed the Southern Ocean, falsify his navigation logs, then slip back in for the return leg to England. As last-place finisher, he assumed his false logs would not receive the same scrutiny as those of the winner.

Since leaving, Crowhurst had been deliberately ambiguous in his radio reports of his location. Starting on 6 December 1968, he continued reporting vague but false positions and possibly fabricating a log book; rather than continuing to the Southern Ocean, he sailed erratically in the southern Atlantic Ocean and stopped once in South America to make repairs to his boat, in violation of the rules. A great deal of the voyage was spent in radio silence, while his supposed position was inferred by extrapolation based on his earlier reports. By early December, based on his false reports, he was being cheered worldwide as the likely winner of the race, though Francis Chichester publicly expressed doubts about the plausibility of Crowhurst's progress.

After rounding the tip of South America in early February, Moitessier had made a dramatic decision in March to drop out of the race and to sail on towards Tahiti. On 22 April 1969, Robin Knox-Johnston was the first to complete the race, leaving Crowhurst supposedly in the running against Tetley for second to finish, and possibly still able to beat Knox-Johnston's time, due to his later starting date. In reality, Tetley was far in the lead, having long ago passed within 150 nautical miles (278 km) of Crowhurst's hiding place; but believing himself to be running neck-and neck with Crowhurst, Tetley pushed his failing boat, also a 40-foot (12 m) Piver trimaran, to the breaking point, and had to abandon ship on 30 May. The pressure on Crowhurst had therefore increased, since he now looked certain to win the "elapsed time" race. If he appeared to have completed the fastest circumnavigation, his log books would be closely examined by experienced sailors, including the experienced and sceptical Chichester, and the deception would probably be exposed. It is also likely that he felt guilty about undermining Tetley's genuine circumnavigation so near its completion. He had by this time begun to make his way back as if he had rounded Cape Horn.

Crowhurst ended radio transmissions on 29 June. The last log book entry is dated 1 July. Teignmouth Electron was found adrift, unoccupied, on 10 July.

Mental breakdown and death

Crowhurst's behaviour as recorded in his logs indicates a complex and conflicted psychological state. His commitment to fabricating the voyage reports seems incomplete and self-defeating, as he reported unrealistically fast progress that was sure to arouse suspicion. By contrast, he spent many hours meticulously constructing false log entries, often more difficult to complete than real entries due to the celestial navigation research required.

The last several weeks of his log entries, once he was facing the real possibility of winning the prize, showed increasing irrationality. In the end, his writings during the voyage – poems, quotations, real and false log entries, and random thoughts – amounted to more than 25,000 words. The log books include an attempt to construct a philosophical reinterpretation of the human condition that would provide an escape from his impossible situation. It appeared the final straw was the impossibility of a noble way out after Tetley sank, meaning he would win the prize and hence his logs would be subject to scrutiny.

His last log entry was on 1 July 1969; it is assumed that he then jumped overboard and drowned. The state of the boat gave no indication that it had been overrun by a rogue wave or that any accident had occurred which might have caused Crowhurst to fall overboard. He may have taken with him a single deceptive log book and the ship's clock. Three log books - two navigational logs and a radio log - and a large mass of other papers were left on his boat; these communicated his philosophical ideas and revealed his actual navigational course during the voyage. Although his biographers, Tomalin and Hall, discounted the possibility that some sort of food poisoning contributed to his mental deterioration, they acknowledged that there is insufficient evidence to rule it, or several other hypotheses, out.

Aftermath

Teignmouth Electron was found adrift and abandoned on 10 July 1969 by the RMV Picardy, at latitude 33 degrees 11 minutes North and longitude 40 degrees 26 minutes West.[15] News of Crowhurst's disappearance led to an air and sea search in the vicinity of the boat and its last estimated course. Examination of his recovered logbooks and papers revealed the attempt at deception, his mental breakdown and eventual suicide. This was reported in the press at the end of July, creating a media sensation.

Prior to the deception being revealed, Robin Knox-Johnston donated his £5,000 winnings for fastest circumnavigation to Donald Crowhurst's widow and children.[16] Nigel Tetley was awarded a consolation prize and built a new trimaran.

Teignmouth council considered a proposal to exhibit the boat, charging visitors 2/6d per head, with profits to go to Crowhurst's wife and four children.[17]

Teignmouth Electron was later taken to Jamaica and was sold multiple times, most recently in 2007, to American artist Michael Jones McKean. The boat still lies decaying on the southwest shore of Cayman Brac.[18] Its location is 19°41'10.40"N 79°52'37.83"W.[19]

Literary and dramatic treatment

Film and television

- Horse Latitudes was a 1975 television movie about Crowhurst (called Philip Stockton in the film).[20]

- One episode of the 1979-80 BBC drama Shoestring had the title character involved in a plot that bore a striking resemblance to the Crowhurst story. "The Link-up" first aired in November 1979 features Jimmie Colefax who is trying to sail around the world in a home-made boat. An amateur radio ham discovers that all his broadcasts actually come from a shed in Bristol.

- The 1982 French movie Les Quarantièmes rugissants is directly inspired from the Crowhurst history.

- The 1986 Soviet film Race of the Century ("Гонка века") gave a dramatic presentation of the events of the Golden Globe Race and the fate of Donald Crowhurst. The movie focused on the idea of competition in a capitalist society as a soul-consuming "rat race", where all community members including children are under constant pressure, and failure and poverty are not tolerated. It portrayed Crowhurst as a deeply honest man being forced into a dangerous unwinnable enterprise by his disastrous financial situation and the greed of his entrepreneur Best. The screenplay took some liberties with the facts, such as downplaying Crowhurst's role in his own destruction, and reporting Tetley as having been killed in a wreckage instead of committing suicide many years later (probably to increase the tension). Crowhurst's suicide is ascribed chiefly to the inability of a moral person to survive in an immoral society. The film's highlights include a realistic depiction of sailing, an endearing portrayal of the Crowhurst family, and a dramatic enactment of Donald's descent into insanity leading to fatalism. This film has passed unnoticed, and today it is known mainly because Natalia Guseva (Наталья Гусева) played the role of Crowhurst's daughter Rachel.

- British artist Tacita Dean created two video works entitled Disappearance at Sea, partly inspired by the story of Donald Crowhurst. She has also written about Teignmouth Electron, journeying to Cayman Brac to visit the wreck of the boat.[21][22]

- Film Four commissioned a documentary based on the affair in 2006, called Deep Water. The film reconstructs Crowhurst's voyage from his own audio tapes and cine film, interwoven with archive footage and interviews. It was described as 'fascinating' by the New York Times upon its release.[23]

- In October 2013, it was announced that Colin Firth and Kate Winslet were in discussions to star in a film about Crowhurst and his wife Clare. Filming for The Mercy, directed by James Marsh, took place in Teignmouth, Devon, in June 2015, with Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz in the lead roles, supported by David Thewlis, Ken Stott and Jonathan Bailey.[24][25]

- 2015 saw the release of Crowhurst, directed by Simon Rumley. The executive producer of the film was Nicolas Roeg, who had himself attempted to film the story in the 1970s.

Stage

- In the 1991 Edinburgh Fringe Festival a one-man stage play "Strange Voyage" was performed in the former Ukrainian Church Halls on Dalmeny Street in Leith. The story was based upon Donald's diaries and broadcast messages sent and received, creating a haunting story of lost hope and looking at the issue of choosing death rather than shame.

- Playwright/actor Chris Van Strander's 1999 play Daniel Pelican adapted the Crowhurst story to a 1920s setting. It was staged site-specifically aboard New York City's FRYING PAN Lightship.

- In 1998 the New York-based theatre group The Builders' Association based the first half of their production "Jet Lag" on Crowhurst's story, although they changed the character's name to Richard Dearborn. (See G. Giesekam, Staging The Screen, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, 151–6)

- Jonathan Rich's play "The Lonely Sea" was runner-up in the Sunday Times International Student Playscript competition in 1979 and was performed by the National Youth Theatre in Edinburgh that year. It was premiered professionally in 1980, as "Single Handed" at the Warehouse Theatre in Croydon.[26]

- The opera "Ravenshead" (1998) was based on Donald Crowhurst's story. Steven Mackey (composer), Rinde Eckert (solo performance), The Paul Dresher Ensemble (orchestra).

- Actor and playwright Daniel Brian's award-winning 2004 stage play 'Almost A Hero', dealt with Crowhurst's voyage, descent into madness and death.

- In 2015, Calgary, Canada-based Alberta Theatre Projects in association with Ghost River Theatre premiered the multimedia-heavy "The Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst" by Eric Rose and David Van Belle.[27]

- In 2016, Ottawa, actor Jake William Smith portrayed Crowhurst in a one-man show entitled "Crow's Nest" at the Fresh Meat Festival.[28]

Novels

- In 2009, Isabelle Autissier, herself a renowned sailor, published the novel Seule la mer s'en souviendra (roughly translates as "Only the sea will remember") based on Crowhurst's voyage.

- The 1993 book Outerbridge Reach by Robert Stone (Dog Soldiers, Children of Light) is a novel inspired by the reporting on Crowhurst.

- The title character of Jonathan Coe's 2010 novel The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim is driven by his obsession with Crowhurst's story.

- In the 2010 travelogue 'Travels with Miss Cindy' towards the end of an exhausting six day solo passage, Donald Crowhurst comes aboard the tiny catamaran and pilots Miss Cindy toward Teignmouth Electron on the beach at Cayman Brac.[29]

Poetry

- American poet Donald Finkel based his 1987 book-length narrative poem The Wake of the Electron on Crowhurst's life and fateful voyage.

Other

- Psychiatrist Edward M. Podvoll, MD, included an in-depth account of Donald Crowhurst's journey in his 1990 book titled "The Seduction of Madness: Revolutionary Insights into the World of Psychosis and a Compassionate Approach to Recovery at Home", published by HarperCollins. The account focuses on Crowhurst's journals and the changes and decline in mental status that the entries reveal.

- British musician the Third Eye Foundation released a song called "Donald Crowhurst" on the album Ghost.

- British jazz musician Django Bates included a track called "The Strange Voyage of Donald Crowhurst" on his 1997 album Like Life.[30]

- Scottish band Captain and the Kings released a single in early 2011 entitled "It Is The Mercy", based on Crowhurst's exploits.[31]

- British band I Like Trains wrote a song called "The Deception", which appears on their album Elegies to Lessons Learnt, based upon Donald Crowhurst's story.[13][32]

- South London hardcore band Lay It On The Line released 'Crowhurst' - a 9 song re-telling of Crowhurst's story - in 2013.

- Folk singer, actor and writer Benjamin Akira Tallamy wrote and recorded "The Teignmouth Electron" based around Crowhurst's breakdown and his death at sea. The song was released on October 19, 2014 with a music video uploaded to YouTube on the same day.[33]

- The band Crash of Rhinos released the song "Speeds of Ocean Greyhounds" in 2013. It appears as the closing track on the band's second and final album "Knots" and was written about Crowhurst's voyage and last days at sea.

- The band OSI has a song named "Radiologue", released on their third album, Blood, which appears to be inspired by the story of Crowhurst.

References

Notes

- ↑ Tomalin & Hall (2003), p. 1.

- ↑ Tomalin & Hall (2003), p. 3.

- ↑ Supplement to the London Gazette. 18 August 1953. p. 4476. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Supplement to the London Gazette. 7 September 1954. p. 5132. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Harris (1981), p. 223.

- ↑ Supplement to the London Gazette. 10 April 1956. p. 2081. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Supplement to the London Gazette. 20 November 1956. p. 6566. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Harris (1981), pp. 223–24.

- ↑ http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/247176.html

- ↑ A Voyage for Madmen, by Peter Nichols; page 17. Harper Collins, 2001. ISBN 0-06-095703-4

- ↑ A Voyage for Madmen, page 30.

- ↑ http://www.moneysorter.co.uk/calculator_inflation2.html#calculator

- 1 2 http://www.iliketrains.co.uk/timeline/essay3.html?height=500&width=500

- ↑ Tomalin, Nicolas; Hall, Ron. The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Harris (1981), p. 214.

- ↑ Harris (1981), p. 217.

- ↑ The Straits Times, 15 July 1969, Page 3

- ↑ "Brac's land wreck makes it to TV fame". Cayman Net News. 17 June 2005. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- ↑ "Wreck of the 'Teignmouth electron'". Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ Horse Latitudes IMDB. Accessed July 19, 2016

- ↑ Disappearance at Sea, by Tacita Dean.

- ↑ Aerial View of Teignmouth Electron, Cayman Brac, by Tacita Dean, 16 September 1998.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/24/movies/24deep.html?_r=0

- ↑ Baz Bamigboye (2013-10-31). "Colin Firth and 'sea widow' Kate Winslet hit choppy waters in new film". Daily Mail UK. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Hollywood A-Listers in Teignmouth to film Crowhurst movie

- ↑ "Warehouse Theatre History".

- ↑ http://www.atplive.com/2014-2015-Season/Last-Voyage/index.html

- ↑ https://newottawacritics.com/2016/10/21/crows-nest-a-promising-hatchling/

- ↑ "Travels with Miss Cindy. Adventures with a 16' Microcat cruiser.". Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ Scott Yanow. "Like Life - Django Bates - Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards - AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ "New Singles Review: Captain And The Kings – It Is The Mercy * Single of the day * release date 7/3/2011". Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ http://www.aversion.com/news/news_article.cfm?news_id=9568

- ↑ "The Teignmouth Electron - Benjamin Akira Tallamy". YouTube. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

Bibliography

- Tomalin, Nicholas; Hall, Ron (2003) [1970]. The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-07-141429-0.

- Harris, John (1981). Without Trace. Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-11120-7.

- Nichols, Peter (2001). A Voyage for Madmen. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-095703-4.

Further reading

- The 1999 book Fakes, Frauds, and Flimflammery by Andreas Schroeder, devotes an entire chapter to Crowhurst's adventure.

External links

- Teignmouth Museum at the Wayback Machine (archived 12 February 2003) – includes map of actual and false journey